Review by James Holden

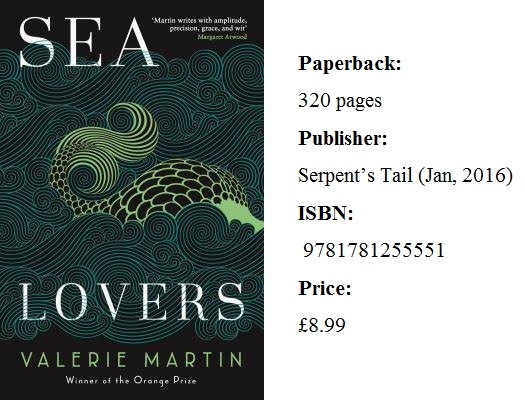

Former Orange Prize winner Valerie Martin has pulled some of her stories previously published between 1982 and 2014 together for this collection, which is arranged into several themes rather than chronologically. So rather than being broken down into sections reflecting the publication date of collections, there are twelve stories equally arranged into Among The Animals, Among the Artists, and Metamorphoses.

In the introduction, which frankly discusses how her writing has evolved over thirty years, Martin says that ‘the question “Are we animals or are we something else?” has engaged my imagination throughout my writing career, and I have addressed it most particularly in short stories.’ Her answer is ‘we are neither, and we are both’, and it is a hugely entertaining journey that she takes the reader on to reach this equivocal conclusion.

The stories where this is most obviously explored is two pieces of magical realism featuring the sexual exploits of mythical creatures, both in Metamorphoses. The title story is about a mermaid who gets tangled up with a drowning sailor, but this is no Ariel or Splash-style romantic portrait. Not only is she ‘weary tonight and her heart is heavy from so much solitude’, but Martin also strips away some of the sex appeal of mermaids:

Her strong arms close around him, and he can feel her cold, clawed hands in his hair. His face is wedged against her shoulder, and as he breaths in the peculiar odour of her skin, he is filled with terror … What he sees paralyses him, as surely as if he had looked at Medusa, though it is so dark that he can make out only the glitter of her cold, flat lidless eyes, the thin hard line of her mouth, which opens and closes beneath his own.

A counter-point to this is provided in the tender ‘Et in Acadiana Ego’, about a centaur. Heading into her stable one night to check a disturbance:

Mathilde could see another horse, and that man, that Nikos, in the narrow space. The alien horse’s rear legs were jammed into the corner, his forelegs raised, his hooves curled over Choux-fleur’s trembling shoulders. Mathilde was an experienced horsewoman; she knew what she was seeing, but what vexed her eyes was the position of the man. Nikos had somehow gotten between the struggling animals. He clung to the filly’s neck, his eyes wide and his lips curled back, grunting and wheezing like a pig stuck in the throat. Was he sitting on Choux-fleur’s back? “What are you doing?” Mathilde exclaimed, hastening to unlatch the gate. “Get back,” Nikos shouted. “Don’t open that gate.” But Mathilde ignored him, and as the wooden dowel slipped free, the door drifted open on its hinges, giving her a full view of the impossible coupling which came apart as she staggered backward.

Both of these stories raise questions about appropriate relationships with mythical creatures – is it okay for a centaur to have sex with a horse? What about Mathilde’s developing relationship with Nikos? But the romanticism running through ‘Et in Acadiana Ego’ provides a wonderful contrast to ‘Sea Lovers’, successfully creating a memorable heroine along the way.

Animals repeatedly pop up throughout the rest of the book, predominantly in the short stories falling under ‘Among The Animals’. In the brilliant ‘Spats a woman’ struggles to cope with the two dogs her departing partner has left behind. There’s also pair of lost cats, and in the Consolation of Nature a mother and daughter fight a guerrilla war against an invading rat in the face of a sceptical husband. In these short stories people struggle to control and relate to animals, or know how best to help them.

Although there are rabbits and more cats in ‘Among The Artists’, the focus is instead on painters, novelists, poets and dancers. None of the artists here are happy with their work, or the compromises needed for success or even day to day survival: even the successful writer in ‘The Unfinished Novel’ frets about the worth of his own work in comparison to the unpublished work of a former lover.

Like many of the short stories across the whole collection, they are not overtly preoccupied with the question posed in the introduction but more concerned with fracturing or fractured relationships, or looking back on relationships that could have been. These stories are littered with abandoned lovers, and people whose relationship is on the verge of breaking down.

For the most part these stories are set in the here and now, the key exceptions being Et in Acadiana Ego, and a delicious slice of southern gothic, The Incident at Villedeau, which is one of a number of outstanding stories in this collection. The short story is about the first murder in a rural Louisiana town for fifteen years, although:

Octave Favrout didn’t deny he had killed Felix Kelly, but he claimed he had acted in self-defence. While hunting near Baie d’en Haut he spied through the foliage a fierce creature as big as a man which he took to be a bear. When this apparition charged him, in his terror he fired a single shot. Then he heard the cry and understood that the crazed animal was of the human variety.

Martin’s short stories are heavily plotted – rich with action, taking their time and containing the occasional smile-raising incident. The longest story here is just shy of 60 pages, but they do not always reach the definitive conclusion that some readers look for in a short story, instead showing exerts from the often miserable lives of her characters.

Despite the sheer amount of heartache on offer, Martin is brilliant at quickly sketching out characters and their circumstances. One husband is ‘an unprepossessing man, tall, balding, his large features crowded anxiously in the centre of his face as if they intended to make a break for freedom’. Someone else is described as being ‘forty years old, twice divorced, a woman who, half a century ago, would have been a statistical failure. But she didn’t feel like a failure at all.’ Some eceb seem to adopt animal characteristics: one has a ‘doglike manner’, another’s ‘memory causes Lydia’s upper lip to pull back from her teeth.’

Looking back across the collection as a whole, it’s possible to read these short stories differently in conjunction with the statement in Martin’s introduction. Spats is clearly about the grief of dealing with unwanted desertion, but it’s also about exerting control over another pack member. The Consolation of Nature is about getting rid of a pest, but is it also about marking territory?

This is a clever and dense collection of short stories, throughout which Martin tackles twin questions: of the impact of romantic partners – current, former or potential – on our lives, as well as the question of the extent to which we are animals. Perhaps it is this emotional impact of relationships that lifts us above animals – perhaps the inability of these characters to make other people happy show that at heart we are much more selfish, animalistic, beings than we would prefer to admit. Either way, this is a superb collection.

James Holden has had his short stories published by Silver Apples Magazine and On The Premises, and performed by Liars League. He lives in a retirement village in north London with his wife and two children, despite only being in his thirties