Review by James Holden

In one of the short stories in this collection by The Whole Kahani, a character is asked whether she feels English, British or Indian. ‘“Wholly of one culture? A bit of both? Disconnected from both?”’ To which the narrator responds:

‘“I think of myself as multifaceted, blessed. I am not A or B; I am A+B, I am lucky to draw the best from both cultures.”’

This exchange underscores the central mission of The Whole Kahani, a collective of British fiction writers of South Asian origin, who aim to ‘give a new voice to old stories and increase the visibility of South Asian writers in Britain.

In practice this means that the ten stories in this smartly produced and engaging volume eschew stereotypical stories about the experience of the South Asian diaspora in Britain. Instead they reach from Britain into South Asia and back again, tackling universal themes rather than culturally-specific tales. And this collection is not just merited by the group’s diverting remit, but by the quality of work here and the emerging profile of the group’s members: their work has been performed on Radio 4, featured in a variety of anthologies, and found acclaim through the Haruki Murikami competition, the Writeidea Short Story Prize, and the TSS’s own Short Story Prize.

Stories here broadly break down into two sections – stories where a South Asian identity is key to the protagonist, and stories where it is incidental. But even this broad dichotomy doesn’t really hold, as the stories cross this boundary in unexpected ways. It’s also notable that where the stories are set in the UK they aren’t about the ‘migrant experience’ and racism is only mentioned once in the book, and even then it’s a fleeting reference.

As the title suggests, love is frequently a preoccupation of this collection, but the authors confidently juggle a wide range of themes – often with the space of a ten page story. The other thing that really marks this book out is the distinctive characters that weave their way throughout, who often have more depth to them than the quirk that initially draws you in.

The book opens with C.G. Menon’s ‘Watermelon Seeds’, about preparations for a school play and a holiday with extended family. Menon has a beautifully evocative writing style (I used to be in a writing group with her), and whilst it is set in Malaysia, the characters and predicament underpinning the story are universal and touchingly explored, and there are so nice touches look at the strange language that adults use.

‘Rocky Romeo’ by Dimmi Khan throws up the first of a number of memorable characters in this book – a London based web-cam performer who ‘rinses’ his female admirers but is afraid of human intimacy. The other characters are memorably drawn, but Rocky is superbly conceived, and steals the show as he struggles to achieve the connection he feels has been missing his whole life.

Radhika Kapur’s ‘The Nine Headed Raven’ also features a memorable character with Matrika, who has resolved not to lie to people following the death of her mother. It’s set in India with some culturally specific references (‘the desire to know consumed her, invaded her mind like Mahmud of Ghazni invaded India’) but addresses the universal theme of how to say ‘I love you’.

‘The Three Singers’ by Kavita A. Jindal similarly inhabits a culturally specific space, telling the story of a pair of twin sisters who attend an Indian classical choir, but Jindal subverts this by locating the class in a London church. It’s also one of the only stories to explicitly address issues of identity, exploring what it means to be mixed race (the quote at the start of the review is drawn from this story), as well as telling a touching story of twin sisters competing for love.

In ‘To London’, Mona Dash brings Rita back to London from India after a gap of 15 years, reminiscing about the relationship she had with a married man when she was last there. It’s a wistful piece with a wonderfully understated close, and there is great delight to be drawn in seeing a character look at the capital through two different perspectives.

The next two stories both look at domestic abuse, but from different angles. Iman Qureshi’s eponymous Naz leaves home having had enough of her mother’s failure to leave an abusive relationship, and this resilient and chipper woman has her horizons widened in unexpected ways by her new dog. There’s a brutal honesty to parts of this story (‘maybe I shouldn’t be so hard on Mum, if this fluttery thing is what makes her go back to him’) but not much as to overwhelm the whole thing.

‘We Are All Made of Stars’ by Rohan Kar similarly features a distinctive character, with a GP who performs love matches for his patients by plotting a form of astrological chart. It’s a great premise, and Kar skilfully and slowly manoeuvres it from the slightly comic set-up set up into something with a raw edge to it, without the shift in tone jarring the reader.

Reshma Ruia’s ‘Soul Sister’ is instead a meditation on the healing power of literature, but like the previous story tips into something much, much darker. The route she pursues is not immediately obvious but on a second reading feels completely obvious, and she also manages to draw a series of convincing relationships between Suman and the people that surround her.

The final two stories are perhaps the saddest on offer. ‘Entwined Destinies’ by Shibani Lal explores how we cope with the weight of our parents expectations but also how parents can live their live their lives vicariously. Skilfully, this narrative is essentially repeated twice over within 15 pages with different arcs, but with similarly unhappy endings.

Farrah Yusuf speaks to universal fears in ‘By Hand.’ The character of the retired tenant Mr Mason is another of the stand outs in this book, communicating with the landlord and his narrator son through the postal system rather than utilising electronic communication. Yusuf weaves a number of themes throughout this story (bureaucracy, loneliness, death), and despite the depressing subject matter at hand, ends the story – and the book – on a note of comfort.

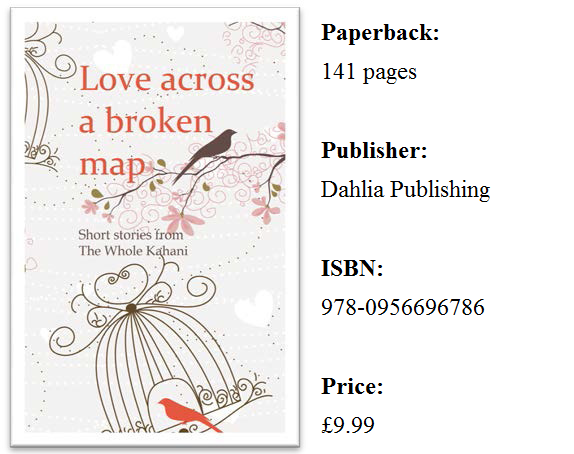

Sadness is touched upon in many of these stories – they touch more upon missed opportunities rather than happy endings, but the book does not feel downbeat. Special mention should also go to the designer responsible for the beautiful cover, and also to whoever inspiration it was that came up with the anthology title.

But ultimately it is the stories that make this such an engaging read. Because what all these stories have in common is that they are strongly driven by interesting and well- drawn characters. Many truths and observations emerge from their mouths over the course of the book, but the group achieves its aim of not tipping into stereotypical depictions of South Asian culture.

James Holden has had his short stories published by Silver Apples Magazine and On The Premises, and performed by Liars League. He lives in a retirement village in north London with his wife and two children, despite only being in his thirties.