Before I begin telling about my journey with Bottled Goods from a 200-word opening to a full-blown novella-in-flash of nearly 35,000 words, let’s talk about the concept of novella-in-flash (the NiF) itself. It’s a form that has emerged in recent years, and as with all new forms, it’s still very open to innovations. If you look at all the interviews with authors of NiFs, their definitions and preferences differ slightly (you can check the essays in My Very End of the Universe from Rose Metal Press, an anthology of 5 NiFs, or the Bath Flash Fiction Award website, in their section that refers to the Bath Novella-in-Flash Award).

Before I begin telling about my journey with Bottled Goods from a 200-word opening to a full-blown novella-in-flash of nearly 35,000 words, let’s talk about the concept of novella-in-flash (the NiF) itself. It’s a form that has emerged in recent years, and as with all new forms, it’s still very open to innovations. If you look at all the interviews with authors of NiFs, their definitions and preferences differ slightly (you can check the essays in My Very End of the Universe from Rose Metal Press, an anthology of 5 NiFs, or the Bath Flash Fiction Award website, in their section that refers to the Bath Novella-in-Flash Award).

For Tiff Holand, it was the character that determined the flow of her NiF. Meg Pokrass compares NiFs with quilts. Aaron Teel wanted to obtain a flow of narration similar to the one of memory, and Michael Loveday’s NiF verges on poetical and often speaks to the reader’s subconscious. Charmaine Wilkerson’s Saboteur-Awards-winning NiF uncoils like a snake, often presenting us the same scene from a different perspective, with each new flash enriching our perception of the real story behind the story. In Ingrid Jendrzejewski’s NiF, the focus is on the exquisite stand-alone pieces in themselves, while a discreet story arc emerges. Stephanie Hutton’s NiF stretches over years, showing us the effects of childhood trauma in adult life.

But all these works, as much as they vary in idea, content, and execution, have one thing in common: they’re longer works with a singular narrative arc, made up of flash fiction that can be read as stand-alones.

The challenge of a NiF is a double challenge: to write small, successfully self-contained stories, and to create a story arc.

When I started writing Bottled Goods, all I had was an opening featuring a young woman at the border of the Socialist Republic of Romania, hiding a terrible secret in her purse. The idea came to me during a flash fiction workshops and over time an entire story arc started emerging. Connections branched out, and secondary storylines – related to this woman’s husband and mother, and to what determined her to leave everything behind and risk defection. There was also magic involved — so there was another storyline referring to how my character, Alina, came to use it.

It was certainly too much to fit into a flash fiction, or a short story.

So I tried to write the story as a novella, but somehow all my narrative drive had disappeared.

At one point, I became familiar with the concept of the NiF. I read My Very End of the Universe and was fascinated by the form. I also heard about the Bath Novella-in-Flash Award, and it became the perfect challenge to get me scribbling (I don’t know about you, but there’s no better motivator for me than a competition deadline).

I had a vague idea about the story arc and about the scenes I wanted to include. So I got a piece of A4 paper, and a bunch of coloured post-its. On each scrap I wrote a title, or a core idea to a flash fiction. At first, my planning board looked patchy: I only ‘mapped’ the crucial moments in my story, and a few more ‘atmospheric’ pieces I was planning to write using prompts. I have to specify — atmospheric pieces, detailing a character or a situation (like ‘Glazed Apples,’ later published in Ambit, or ‘A Key on a Rope, a Shop and a Beggar’) were just as important as the pieces that pushed the narrative arc further. I had to keep character development in mind.

I drafted for a month and a half. I had an output of a new piece every two or three days (which never happens, otherwise). But I found it so easy to write while I knew the characters and I had a ‘master plan’ for them. Also, I felt that the format gave me a lot of freedom, since I didn’t have to write the pieces in chronological order.

Bottled Goods was the most fun writing project I’ve ever worked on.

As I finished writing the planned pieces (at ca. 14,000 words), I hit a wall. In my eyes, my draft was sheer perfection. But I was sure it wasn’t quite there. It was time to bring in the fresh eyes FlashForceFour, my writing group: Christina Dalcher, Stephanie Hutton and Kayla Pongrac. The girls loved the idea behind my NiF, but pointed out there were holes in plotting, and especially regarding Alina’s relationship with her mother. Christina even suggested the unimaginable for a flash fiction writer: preparing a synopsis for the novella.

Of course I moaned and told myself that it was impossible. I was inexperienced in writing synopses, and I perceived it as a very particular form of torture. My novella had grown organically, and there were so many ramifications and implications, impossible to pin down in a single page. But I did it in the end and I was able to identify the weak spots in my work. And I didn’t stop there. I had recently read ‘Save the Cat’ by Blake Snyder, recommended by another writer friend, Gillian. The book, written by a Hollywood screenwriter, mostly deals with plotting. I used Blake Synder’s famous ‘beat sheet’ to time the beats in my own (already written) book. Luckily, most of them were there, even though I hadn’t consciously thought about them as I did my own rudimentary plotting (like, for instance, the catalyst in the form of Mihai’s defection). But some beats needed refining and figuring them out was logical work with the pencil in hand.

Of course I moaned and told myself that it was impossible. I was inexperienced in writing synopses, and I perceived it as a very particular form of torture. My novella had grown organically, and there were so many ramifications and implications, impossible to pin down in a single page. But I did it in the end and I was able to identify the weak spots in my work. And I didn’t stop there. I had recently read ‘Save the Cat’ by Blake Snyder, recommended by another writer friend, Gillian. The book, written by a Hollywood screenwriter, mostly deals with plotting. I used Blake Synder’s famous ‘beat sheet’ to time the beats in my own (already written) book. Luckily, most of them were there, even though I hadn’t consciously thought about them as I did my own rudimentary plotting (like, for instance, the catalyst in the form of Mihai’s defection). But some beats needed refining and figuring them out was logical work with the pencil in hand.

It was the best thing that happened to my novella, and I think it gave it some commercial appeal. Some, not all of it. On accepting my manuscript for publication, my publisher, Fairlight Books, pointed out that there was still too much white space between certain flash fictions. Other scenes had been glossed over too quickly (like the scene at the Border, which is the most tense section in Bottled Goods). My NiF might have been good enough for the average flash fiction reader, ‘trained’ to fill in the white space, but it was too much for a reader of longer fiction. This made me think a lot about my public and making my work accessible.

So, I was back to the drawing board — but it was so much easier for me now to round off my novella. I was in control of the voice, of my characters, I knew exactly what I wanted to write (I find it very easy to edit when I receive precise and comprehensive feedback, like the one my writing group and my publisher gave me). At the end, I had a work of nearly 35,000 words — Bottled Goods in its final shape.

And a last point regarding my writing process. Early on, I’d decided to use unusual structures in the flash fictions that formed my NiF, to vary the perspective a bit, and to explore the borders of storytelling. It was a bit of good fun during an already enjoyable process. Bottled Goods employs flash fictions written as a letter to Santa (Father Frost in Romanian lore), a diary entry, a timetable, a mini-instruction manual, commented quotes, a flash told in backwards order, a list, a table, a series of postcards.

Did some readers feel that it disrupted the narrative flow? Yes, they did. But for every one of them there were many more who told me they appreciated the innovations. Did I feel that the unusual flashes served the novella as a whole, and made it complete? Most certainly. And if I were to do it all over again, I’d do just the same.

***

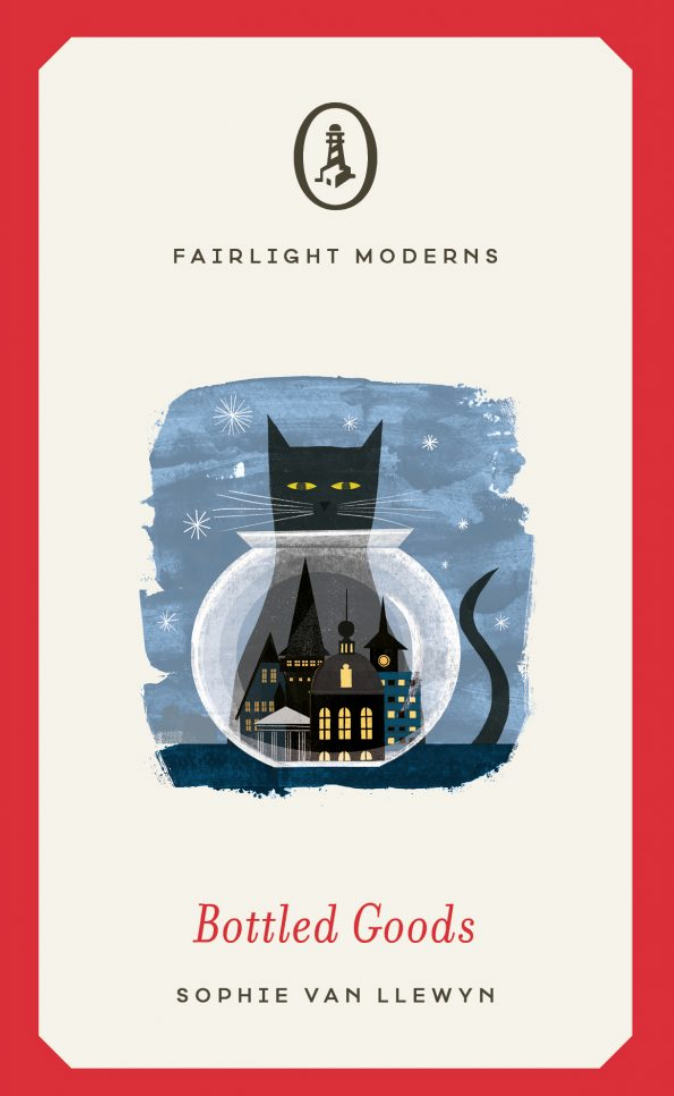

Sophie van Llewyn was born in Romania. She now lives in Germany. Her prose has been published by Ambit, the 2017 & 2018 NFFD Anthologies, New Delta Review, Banshee, New South Journal etc. and has been placed in various competitions – including TSS (you can read her Flash Fiction ‘The Cesarean’ here). Her novella-in-flash, ‘Bottled Goods,’ set against the backdrop of communist Romania, is available from Fairlight Books.

Learn more about our Flash Fiction competitions.

Submit an article to TSS.

Support TSS Publishing by subscribing to our limited edition chapbooks