Review by Kate Tyte

Publisher: Three Impostors Press

Publisher: Three Impostors Press

269 pages

RRP £10.00

ISBN 978-1-78461-704-2

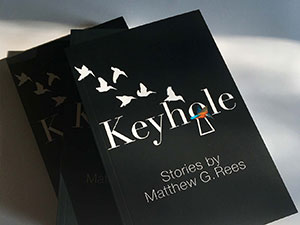

Three Impostors Press is a small publisher established in Newport, south Wales in 2012, with the aim of producing high quality, scholarly versions of interesting, rare and out-of-print books, along with other related new writing. It is named after a book by Arthur Machen, an early Welsh master of fantastic and horror fiction of the late Victorian and Edwardian period. Three Impostors has published several Machen-inspired short stories, including a stand-alone version of ‘The Word’ by Rees, which also appears in this collection. Rees has a PhD in creative writing and edits the online horror magazine Horla. This is his first collection.

Keyhole features eighteen weird tales. It begins with an epigraph from Machen: ‘the unknown world is, in truth, about us everywhere…’ and is obviously influenced by Machen and other Edwardian writers of the fantastic like MR James. There is a donnish, genteel, delicate quality to much of the writing, off-set by black humour and a nasty, cruel streak. Some of the tales are comic, some surreal, some sentimental, but most have an unsettling undercurrent of suspenseful menace. Where there is violence it is usually implied rather than described in gory detail.

All of the stories in Keyhole are set in Wales, and most of them focus on a single location: isolated farms, the remains of a ruined military hospital, a mysterious Second-World War era installation that only appears on the beach when the tide is exceptionally low, ‘an ugly jumble of cones and cubes made from concrete that resembled dirty porridge.’ The locations are so vividly described it feels as though Rees must surely be describing them from memory; a strange odyssey around the weirder, bleaker parts of his country. Iain Sinclair drew on Machen in his psychogeography, and Rees in turn takes influence from psychogeography, as well as the pathetic fallacies typical in gothic literature: ‘The autumn was long and jealous. It held the valley in its skirts for weeks.’ The sense of place is so strong in these stories that it feels as though Rees has taken real places as his starting point, rather than starting with a character or an idea. As the setting for an unsettling tale, a series of isolated, decaying properties in an underpopulated landscape is pretty standard fare, but Rees manages to invest each location with singular oddness and intensity. In the hospital ‘Forests of fungi with caps in colours of rust and slate marched across walls, some bare, some hung with huge curtains of rotting red and green paper which slumped and sagged like abandoned banners…’

Ghosts abound in Keyhole: characters are haunted by their childhoods and the physical ghosts of the recent past are everywhere, from World War Two relics to the decaying ruins of a once-thriving industrial and agricultural economy, where butchers and bakers have been replaced by coffee shops and nail bars. But however ghastly and superficial the modern world might be, the old world was no better. History doesn’t peer through the skin of the landscape not like a lovely palimpsest but like a grinning skull. Several of the stories feature disorienting time-shifts, where past and present bleed into one another.

‘The Service at Plas Trewe,’ is the most traditional ghost story. The narrator recounts his journey from troubled youth to successful hotelier in a haunted country house. The narrator has an extremely Edwardian style – he explains he picked up his taste for words from the hotel’s very fine library – which jars deliciously with incongruous modern details like ‘a spray-tanned wrist.’ The story twists and writhes in unexpected directions: our anti-hero has an unsavoury past, strong feelings about politicians, and the archives of the 1913 fishing season carry a ghastly premonition of the First World War. The dénouement delivers a surprising sting that manages to bring something different to the ghost story.

Many of the characters in Keyhole are escaping, fleeing from city life or from their pasts and retreating to a ‘better’ way of life. These are idealistic hippie types: ‘snail farmers, poets, sculptors, ukulele makers…’. Others are returning to their roots, reluctantly or otherwise: traditional lifestyles replaced by people simply playing at traditional lifestyles. But Mother Nature is not kind to people with high expectations and limited practical experience. In ‘Rain,’ one of my favourite stories in the collection, a couple and their young children enjoy their idyllic self-sufficient life on a smallholding, until the rain dries up. Nature shimmers in beautiful, elegiac descriptions, even as a sense of dread creeps from the first page. When father and son discover that the reservoir is empty ‘the feeling I had was one of being inside something enormous that had died: there… at the top of our valley. I would describe it now as like being in the picked carcass of an elephant.’ ‘Rain’ is narrated by a man looking back on his childhood and Rees really captures a child’s attention to the tiny details of his world and the magical power children ascribe to everyday objects. The narrator is plagued by an obscure, liminal sensation that his parents are somehow untrustworthy or responsible for their plight, and the horrifying events unfold, drop by appalling drop.

A couple of the stories have a very Roald Dahl-ish Tales of the Unexpected flavour, and feature unpleasant characters getting a satisfyingly awful comeuppance. ‘Driftwood,’ is a glorious comic piece which wreaks a totally bizarre vengeance on the main character. ‘Queen Bee,’ concerning the rivalry between an interloper and an established beekeeper who comes to a sticky end, is even more Dahl-ish. Sometimes I didn’t find Rees’s handling of this type of story so satisfying. In order to make the reader really relish the sadism, we need to feel that the character richly deserves their fate. And some of Rees’s characters are a little too sympathetic. In ‘The Lock,’ a property developer who wants to despoil the landscape with a golf resorts, partly out of a desire for vengeance against a difficult childhood, gets what’s coming to him. I loathe golf resorts and I wish extreme evil visited upon those who profit from them, but I also have a strong desire to see people triumph over adverse childhoods, so I felt very conflicted. Perhaps that is the point: maybe Rees wants his readers to be faced with a world in which terrible things can happen to merely averagely bad people.

In Rees’s best stories, like ‘Rain,’ ‘I’ve Got You,’ and ‘Bait Pump,’ the fantastic and the real are held in perfect tension: the sense of something other illuminates an everyday horror. In all truly great horror stories the monsters are symbolic of something, even if that something is completely ambiguous. Keyhole’s real horrors are the callous indifference of nature, grief, loneliness, child abuse and our own sins catching up with us. But some of Rees’s stories skew so much towards the fantastic that they neglect the real. We’re left with horrors that are so unique that they cease to be horrifying, because they are too particular and don’t appear to have a deeper level. Rees’s inventiveness and rejection of cliché is one of this collection’s strengths, but there’s a reason why horror is frequently clichéd: most people are afraid of the same things. ‘The Press’ and ‘The Cheese,’ were examples of this issue. In ‘The Cheese’ an unsuccessful writer at a small literary festival is menaced by a hypnotic cheese obsessive. Rees could have gone the route of Carmen Maria Machado here, and used a fantastical element to make this all-too familiar situation truly horrifying. After all, most women find themselves fending off the unwanted attention of strange men on an exhaustingly regular basis. We ask ourselves the familiar questions: is this guy a harmless weirdo or is he dangerous? How can I get out of this situation? But Rees’s character seems oblivious to danger. She doesn’t ring psychologically true, so the events that follow lack the emotional resonance that comes from the interplay between the weird and the realistic.

Keyhole is a little uneven. The collection runs quite long and I wonder whether some of the less effective stories could have been excluded, leaving the whole collection stronger. But at his best Rees has original ideas and an incredible command of style. His great stories are refreshingly different, he paints a startling and detailed portrait of a world slightly askew, and he knows how to cast a spell with a sentence. I look forward to reading more from Rees in the future.

***

Kate Tyte was born in Bath and studied English Literature at Cardiff and York Universities. She worked as an archivist for over ten years, and now lives in Portugal where she works as an English teacher. Her literary essays have appeared in Slightly Foxed magazine issue 55, 59, and forthcoming, and her fiction has appeared on The Fiction Pool website, in STORGY magazine, and in Riggwelter issue 26.

Support TSS Publishing by subscribing to our limited edition chapbooks