Ethnic Tibetans live off the land, roaming across vast, barren terrain. But they never lose their sense of community – and I found one too, with the most unlikely of companions.

Ethnic Tibetans live off the land, roaming across vast, barren terrain. But they never lose their sense of community – and I found one too, with the most unlikely of companions.

Us Brits aren’t exactly known for our dancing abilities. It’s a stereotype, I know – but if you ask a British person to show you their ‘traditional dancing’, chances are they’ll do a sort of hybrid between ‘the robot’ and the type of sliding shuffle you usually see your dad doing at a wedding – both hands pumping in the air, bending his knees, completely out of time.

If you’re no great shakes on the dancefloor yourself, you can perhaps imagine (or empathise with) the feeling of abject horror that descended upon me when I found myself in one of the world’s most remote, beautiful and brutal landscapes – the Tibetan plateau of the Himalayas – and was asked to show an entire community of nomads my “special dance moves”. Not only had they never seen a foreigner like me, before; but they certainly, unequivocally hadn’t seen anyone do the Y.M.C.A.

Yet, there I stood, in the centre of the ‘town hall’ – the largest of a cluster of tents cleverly woven together with black yak hair, impenetrable to the wind howling across the plains outside – shuffling awkwardly, while trying to hum the tune I hoped, desperately, they might recognise.

I waved my arms around as I performed the quintessential four-letter dance moves. Pointed my fingers in between, in semblance of the classic, hip-holster ‘double gun’ stance, trying to look ‘cool’. I probably pursed my lips. I may well have gyrated my hips, too; but I’ve managed to blank out whether or not I closed my eyes, to demonstrate that I was really, really into it – just like you’d have found me doing at Zeus nightclub in Cardiff on a Friday night in 1999, listening to Baby D’s Let Me Be Your Fantasy, at one in the morning.

Thankfully, I wasn’t alone. I was joined by three reluctant dance partners: my then-boyfriend, and an Israeli couple we’d met and hit it off with. They were travelling indefinitely, like us; yet rather than exploring after living and working abroad, as we had, they’d spent more than two years with the Israeli Defence Force (IDF), and were doing what so many young Israelis do to shake off the confines – and trauma – of national service.

Our trip onwards through south-east Asia would later be defined by seeing hordes of IDF graduates taking up smoking spots in cafes and shisha bars in Thailand; burning off steam in backpacker bars in Cambodia, haggling hard in markets in Vietnam and diving deep into the mind-cleansing worlds of yoga and meditation in Laos. Many would tell us of the drive they felt to “reclaim their youth” after giving up their precious teenage years to the frontline. Most were choosing to “cut loose” before they returned to Israel to study at university – and that meant “cutting loose” by way of partying, big time.

But for now, he – an IDF lieutenant – and she, an IDF intelligence officer – were standing self-consciously beside me, showing off their own rhythmic “traditional dance” interpretations; the type of movements we all clearly wished we were doing in private, or in front of very good friends. Yet we’d met just days before, in a hostel in the Tibetan capital of Lhasa, before agreeing to hire a Jeep – and driver – and share the 800 mile, seven-day trek across the stark and mountainous terrain to Kathmandu.

As the epic landscape rolled by out of the window, and we gazed in reverence at the shoreline of the stunning, naturally-turquoise Yamdrok Lake; we got to know each other – comparing notes of the circumstances of our individual journeys out of the regional Chinese capital of Sichuan, Chengdu (famous for giant pandas, of course) to the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR). We agreed it felt, at best, clandestine; at worst, dangerous. Everywhere we went, Chinese officials reminded us – verbally and on paper – that Tibet “didn’t exist”; that Lhasa was “part of China” – despite the then-recent wave of self-immolation suicide protests, mostly by monks and nuns, prepared to die over Beijing’s rule.

Before setting out on our epic road trip to Nepal, we’d visited the Potala Palace in Lhasa together, a dzong fortress-turned-museum and World Heritage Site – previously the winter palace of the Dalai Lamas from 1649 to 1959. There, we witnessed pilgrims with tears streaming down their faces, barefoot, prostrating themselves in front of it. Many were nomads – homeless, poverty-stricken – they had walked for miles, lying flat on the floor every few steps as they made the arduous journey to a spiritual heartland officials repeatedly told them was nothing more than a rumour.

I couldn’t help but compare this ongoing struggle for ‘place’ between ethnic Tibetans and the ruling Chinese, to the environment our new Israeli friends had grown up in – and been brought up fighting for.

As liberal Londoners, it wasn’t entirely easy for us to relate; and we found ourselves involved in heated debates in the back of our 4×4… about religion and anti-Semitism, about Israeli-Palestinian relations, about occupation, terror, war and the treatment of refugees. We clashed over the use of guns and violence and the perceived necessity of national service. They told us we “couldn’t possibly understand” what it was like to grow up fearing attack; and we related to that in the only way that we (then) knew how – by talking of Britain’s history of IRA terror activity in the 1970s and 1980s.

This was before 7/7, before the Manchester Arena bombing, before cars had driven into pedestrians at Westminster Bridge, London Bridge and we’d seen (and in my case, covered at work as a journalist on a national newspaper) the stabbings at Borough Market. The only way we could possibly draw parallels, in early 2005, was referring to a time we were too young to fully remember – or understand.

But away from our ideological clashes, we also found ourselves bonding through shared experiences we knew we’d never repeat again in our lives – staying in Buddhist monasteries, journeying to Everest Base Camp, hanging prayer flags at the high-altitude Simila Pass. Where we could have focused on difference, we found peace in similarity.

We also had to band together for survival. We got caught for an entire day in a roadblock set up by the Chinese Army, who had pulled a tank across the famous Friendship Highway to block the narrow, one-way mountainous road. Our Tibetan driver, who told us to call him ‘Bob’, didn’t seem phased by the interruption. He settled down in his seat, pulled his hat over his eyes, smoked cigarettes out of the window and told us to wait. Only the sternness in his voice when he warned us not to get out of the car belied any sense of danger. After hours of waiting, seemingly for no purpose other than inconvenience, the tank moved and we were on our way once again.

We came together again – literally – to survive when staying overnight at Namtso lake, the highest saltwater lake in the world, at 4718 metres above sea level. To avoid unnecessary environmental impact, there are no hotels or permanent accommodation, and we slept in a small, pop-up corrugated iron shed, devoid of electricity or heating. At night, the temperature dropped so low that a two-litre bottle of water we had with us turned to ice. The physical effects of a prolonged stay at such high altitude were intense and overwhelming; making us sick and dizzy and delirious. One of our friends became so disoriented that she believed the room to be unbearably hot, and began trying to get out of bed and remove her clothes. We had to physically tackle her – the three of us – to talk her down. When we awoke in the early morning, to make a trip up a nearby mountain pass to watch the sun rise, we discovered a dog had died from the extreme conditions; its body frozen solid at the edge of the water.

Leaving Namtso, we began to see sporadic clusters of people – young and old – standing road-side and staring as we roared past in a hail of dust; tyres bumping over rocks and sheet ice. We’d read about them. Ethnic Tibetans, known as the nomadic dropka, or ‘high-pasture’ people of Tibet. They ride horses and yaks; live in tents made from woven yak-hair and roam with their animals across a vast area that stretches across the Himalayan mountains and dips down far into the Chinese provinces of Sichuan and Yunnan. They live a life exposed to the elements; focusing on rearing livestock rather than growing crops. They are instantly recognisable for their woven skirts, wrap dresses and jewellery; for their long, braided black hair, wound around their heads like crowns; for their sheepskin and heavy boots; for their beautiful features, weathered by the wind and harsh temperatures.

Leaving Namtso, we began to see sporadic clusters of people – young and old – standing road-side and staring as we roared past in a hail of dust; tyres bumping over rocks and sheet ice. We’d read about them. Ethnic Tibetans, known as the nomadic dropka, or ‘high-pasture’ people of Tibet. They ride horses and yaks; live in tents made from woven yak-hair and roam with their animals across a vast area that stretches across the Himalayan mountains and dips down far into the Chinese provinces of Sichuan and Yunnan. They live a life exposed to the elements; focusing on rearing livestock rather than growing crops. They are instantly recognisable for their woven skirts, wrap dresses and jewellery; for their long, braided black hair, wound around their heads like crowns; for their sheepskin and heavy boots; for their beautiful features, weathered by the wind and harsh temperatures.

We stopped the car and jumped out, only to be immediately surrounded by children fascinated by our clothes, make-up and possessions. One item that got squirreled away and shared with rapt fascination was a simple blue tub of Nivea. I demonstrated how to use it by rubbing it on my chapped lips; and then watched it pass from hand to hand, diligently shared by every single member of the community; young and old.

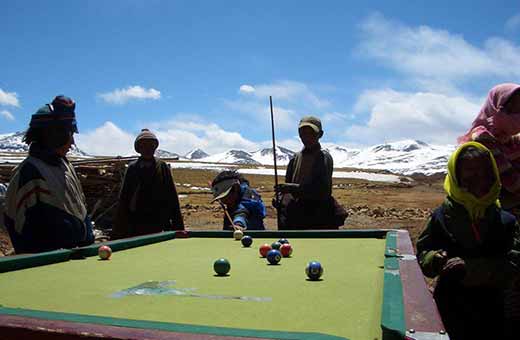

They gestured for us to follow them to something that was obviously the source of great excitement, particularly among the young. It turned out to be a pool table – possibly the highest game of pool ever played in the world.

After that, we were invited in to the ‘town hall’, the large tent that signalled the heart of the community. We stepped inside. A fire was burning, and people were sitting on brightly coloured woven rugs on the floor. We were offered sustenance: yak butter tea and dried yak cheese – so hard it both looked, and felt, like chewing on bone. The tea was salty; so salty I had to fight my body’s natural urge to spit it out. I took tiny sips from a small cup carved out of animal bone, steeling myself not to gag or to vomit.

It would have felt difficult to keep it together, even at the best of times – but at almost 5000 metres above sea-level, not only did I feel like I wanted to be sick, but I was dizzy, too. My lips had taken on a blueish-purple hue, thanks to the lack of oxygen. Walking more than a few steps left me pausing for breath. I felt like I’d aged a couple of decades. We’d eaten meat in Lhasa – varieties of yak: yak burgers, yak cheese, deep-fried yak (slightly tough, slightly minty) – but nothing on the road since except bread, dried noodles and processed cheese. And seeing the Tibetans proudly leading their beloved yaks around outside made me feel terrible. They were perfectly agreeable: proud, hairy and sweet, and we’d recently eaten their brothers or sisters. Not cool.

It would have felt difficult to keep it together, even at the best of times – but at almost 5000 metres above sea-level, not only did I feel like I wanted to be sick, but I was dizzy, too. My lips had taken on a blueish-purple hue, thanks to the lack of oxygen. Walking more than a few steps left me pausing for breath. I felt like I’d aged a couple of decades. We’d eaten meat in Lhasa – varieties of yak: yak burgers, yak cheese, deep-fried yak (slightly tough, slightly minty) – but nothing on the road since except bread, dried noodles and processed cheese. And seeing the Tibetans proudly leading their beloved yaks around outside made me feel terrible. They were perfectly agreeable: proud, hairy and sweet, and we’d recently eaten their brothers or sisters. Not cool.

But then, to top it all off, and with almost zero preparation, using only communicated gestures that made it clear what was being asked of us – with our new, nomad friends sitting quietly and respectfully, watching us with wide and curious eyes – we were asked… to dance.

And dance, we did. I didn’t feel we had any choice. I spun words out of the air with my upper limbs, my boyfriend engaged in some punk-rock moshing, one of the Israelis kicked his legs out repeatedly, as though he were Cossack dancing, while his girlfriend pogoed frantically up and down – and we all studiously and strictly avoided eye contact with each other. Yet, the more we danced, the more I began to relax; until I realised I had accidentally started to enjoy myself.

In turn, I began to laugh, suddenly aware of the surrealness of the situation. I was thousands of miles from home and on top of the world – literally. What’s more, I was with the most unlikely companions – two serving Israeli soldiers – who’d driven with me hundreds of miles across some of the world’s most severe and beautiful mountain ranges. Nobody knew where I was; where we were. And we had been taken in, graciously, by a fiercely proud and independent tribe of people who communicated more often with animals than with outsiders; who had never seen a tub of Nivea before; who knew more about the land and being self-sufficient than any of us ever would. And I was doing the Y.M.C.A.

What I learned at that precise and unforgettable moment from the Tibetan nomads – and from our new Israeli friends – was that being part of a community is so much more than sticking together blindly; seeking comfort in familiarity. On the contrary – it’s about being open to each other; to learning from each other. It’s about listening to someone else’s point of view, or life experience, with compassion rather than judgement. It’s not necessarily agreeing with them, but being willing to walk in their shoes and try to understand, all the same. It’s about not being embarrassed to show how bad you are at dancing, because it really doesn’t matter – as long as you’re having fun. The Village People said it best: “No man does it all by himself”. And what I learned – what I really learned – was to put my pride, right there on the shelf.

***

All photos taken by the author.

Victoria Richards is a journalist and writer. In 2017/18 she was shortlisted in the Bath Novel Award and the Lucy Cavendish College Fiction Prize, was highly commended for poetry in the Bridport Prize and came third in The London Magazine Short Story Competition. A collection of her poetry was published in May 2019 alongside two other poets in Primers: Volume Four, with Nine Arches Press, and in 2020 she came first in the ‘Nature in the Air’ poetry competition, first in the Retreat West ‘Best Opening Page’ competition and second in the Magma Poetry Competition. Find her on Twitter or at The Independent.

We’re a small group of volunteers, dedicated to writers, readers, and publishers. We’re also a paying market and do our best to champion all voices. When the nights are long and cold and the admin piles up, your help reminds us our work is appreciated. We’re hugely grateful for any support you can offer. Thank you.