In September of 1961, when I was sixteen, I flew to Paris. I was to stay with a French family on the first leg of a student exchange. But things got mixed up in a hurry. The family’s grandmother, in Marseille, suffered a series of strokes, causing the mother and father to rush off together to care for an extensive property. The two daughters went with them, so I was left with just my new friend, their son Pascal, at their apartment on Rue Budé, on the Île St. Louis. Then, within a week, Pascal was arrested for, of all things, sedition. He was involved with a radical student organization, or “cell” as it was characterized in Le Monde, dedicated to the realization of self-government for France’s closest possession, Algeria. Bail was out of the question. All France was spooked by the fear of insurgency. After an hour of struggling with long-distance codes, I managed to contact the father in Marseille with the news, but no, he would not return. “Pascal has made his bed with Communists. He will suffer the consequences.” He apologized for deserting me, but said that if I walked daily across the Pont St. Michel, if I purchased a baguette and cheese and then walked for two hours in one of the twelve directions of the clock, if I spoke openly to passersby, my vocabulary would improve and my life would be enriched. “I have told Pascal the same, but he is oblivious to common sense. You shall do better.” We were speaking in French, of course. He instructed me on watering his plants. “Thank you,” I said.

In September of 1961, when I was sixteen, I flew to Paris. I was to stay with a French family on the first leg of a student exchange. But things got mixed up in a hurry. The family’s grandmother, in Marseille, suffered a series of strokes, causing the mother and father to rush off together to care for an extensive property. The two daughters went with them, so I was left with just my new friend, their son Pascal, at their apartment on Rue Budé, on the Île St. Louis. Then, within a week, Pascal was arrested for, of all things, sedition. He was involved with a radical student organization, or “cell” as it was characterized in Le Monde, dedicated to the realization of self-government for France’s closest possession, Algeria. Bail was out of the question. All France was spooked by the fear of insurgency. After an hour of struggling with long-distance codes, I managed to contact the father in Marseille with the news, but no, he would not return. “Pascal has made his bed with Communists. He will suffer the consequences.” He apologized for deserting me, but said that if I walked daily across the Pont St. Michel, if I purchased a baguette and cheese and then walked for two hours in one of the twelve directions of the clock, if I spoke openly to passersby, my vocabulary would improve and my life would be enriched. “I have told Pascal the same, but he is oblivious to common sense. You shall do better.” We were speaking in French, of course. He instructed me on watering his plants. “Thank you,” I said.

I hung up, feeling disheartened. Who could have imagined this? I thought of phoning home but the complexity and the cost were overwhelming. I was on my own. Locking up the apartment, I descended three flights of stairs to the inner courtyard, looking up at jury-rigged laundry lines suspended from various windows. I waved au revoir to the elderly concierge and pushed open the heavy door to the city. I would follow his instructions, I would enrich my life. To that end I crossed the nearest bridge to the Cathedral, raised my eyes to examine the gargoyles—I had no idea of their meaning or import—and then, map in hand, set out in a northerly direction, imagining the hand of a clock pointing to noon.

I first crossed the river, or a branch of it, on the Pont d’Arcole. Soon I found myself in a large public square, and after that the roads narrowed and became more commercial. I passed pastry shops, flower shops. At a boulangerie I purchased, as per my instructions, a sliced half-baguette with cheese and sliced tomatoes, wrapped tightly in white paper. But I was too nervous to eat it on the spot, and there were no benches or green spaces. On I walked, without direct purpose, my sandwich pinched between arm and chest, leaving my hands free for the map. It quickly became clear that Pascal’s father’s advice, to walk in a straight direction, was impractical. Narrow streets branched off at differing angles, drawing me irresistibly off course. I attempted to make corrections, but after an hour or so of indecision I found myself at the foot of a funicular, a short tramline that rose, my map indicated, from Place St. Pierre to the Basilica Sacré-Coeur. I had wandered perhaps four hundred metres from my intended path. Still, not bad, I thought, for my first day.

The fare for the funicular was not exorbitant, but as my funds were limited I took the adjacent stairway, switch-backing through steep parkland, arriving at the top in a well-earned sweat. There I leaned on the ornamental balustrade that overlooked the city. I could not see the river, nor the steeples of Notre-Dame. Feeling hungry at last, I placed my sandwich on the parapet and unwrapped it, but the brie, or camembert, or whatever cheese it was, had melted during my journey. It was oozing from between the cut edges of the baguette, along with juice from the tomatoes. Quickly I replaced it on the parapet, intending to search my pockets for a napkin or handkerchief. Before I could say “Hey!’ or “zut alors!” a wolf-like dog came out of nowhere, sickly-yellow in colour, collarless, bristling. He snatched my meal between his jaws and raced away through a crowd of onlookers. Laughter ensued. I smiled as though equally amused, noticing for the first time how olive-skinned or sunburnt were the faces about me. Perhaps there was an African or Algerian quarter in Paris, and I had stumbled into it.

An elderly lady then approached me, dressed in widow’s black. She was carrying a small tray and offered me, in sympathy, a slice of pizza. I was touched by her kindness, but the main ingredient appeared to be green olives. Therefore I shook my head, but she insisted, holding a piece up to my face, almost pushing it into my mouth. Well, go ahead, I thought, so I took a bite from it. “Very good,” I said, pretending satisfaction, but it was salty to the extreme. She then rubbed her fingers together and produced, with one dexterous hand, from a pocket in her dress, a handwritten bill for 5 francs. “For me?” I asked. “For that slice of excellent pizza, of course,” she said, and so I spent one-half of my daily walk-about money for a salty tongue. I counted out the coins, one by one.

Then I broke free of the gathered crowd, all of whom were openly enjoying my discomfort, smiling, laughing, clapping each other on the back. To escape, I set out to circumnavigate the Basilica. There was a charge for visiting its Dome—curiously Turkish in design—but circumstances worked in my favour. I was swept up in a crowd of tourists from an idling bus, and so I looked over Paris free of charge. I saw my thief, the yellow dog, full of baguette, slink past the funicular. Then I elevated my gaze to the tapestry of the modern city and reflected on her turbulent history, zealots of various convictions turning blood-mad, sweeping through the avenues without mercy. The revolutionary courts, the guillotine, the SS. And where, I wondered, was Pascal? In the Bastille? Did it still exist? And how could his father turn against him so completely while offering me, in his next breath, meticulous advice on the care of African violets. He had seven such plants potted on his windowsill, four more than he had children.

I left Sacré-Coeur. I backtracked through the 9th and the 2nd Arrondissement. I was lost one moment, found the next. Finally I was back to the lengthening shadows of Notre-Dame, then to Rue Budé. The concierge, upon spying me, scrambled to her feet. Bent over by arthritis, she crab-walked my way and blocked the entrance. Her head came to the level of my chest. “Young sir,” she said, “I have opened your apartment to the police. Four of them, with a battering ram. But for me, the door would be in splinters. They left, twenty minutes ago, with parcels.”

At the word police, my breath was taken from me. “Pascal, it must be about him,” I said.

“Pascal? They already have Pascal. They said to me, calling me old woman, report any students, radicals, keep a list of visitors.”

“Madame,” I said, “I know nothing of the politics of France.”

“So you say, so you say, dear boy.”

I detected a ferocious gleam in her eye. She raised both hands and grasped my shirt. “I am with you, my sympathies are the same as those of my fallen husband. Freedom for Algeria!”

I was in deep water, I could see. I pried myself loose and made for the stairway, activating the timer-switch that controlled the lights to the third floor. Darkness therefore followed me step by step as I progressed upwards, as though trouble were tracking me, hard on my heels. The door to our apartment was ajar, but nothing seemed to be disturbed inside. Not in the hallway or the kitchen, the living room, the dining room. But in the bedroom Pascal and I had shared for several nights, there were changes. His books were piled on the dresser, rather than neatly stored on shelves. Several shirts had fallen to the floor of the closet. More germane to me, my passport had moved from the upper drawer of my bedside table to the small desk, pinned under the base of the lamp.

The visitors were telling me something. They knew me, they were watching. And, I thought, I would pay immediate attention. I was the exact opposite of a revolutionary. I would go to the police in the morning and explain myself. Phone home for advice? My parents would laugh, disbelieving, and what could they do. I went out to Rue St. Louis and purchased items at a small grocery, two nectarines, a replacement baguette, slices of ham, a firmer cheese. Then I sat by the Seine in softening light as the tourist boats kicked up small waves against the embankment. Dusk solidified the flying buttresses of the church. My situation was unique, but not precarious. I could reassure the authorities. They would say, “Canadien errant, go about your language studies.”

Returning to the apartment, by chance I passed a Préfecture de Police, but it was closed at that hour. The next morning, however, I was third in line when the doors opened, and soon I was speaking to a uniformed young man, showing him my passport, explaining as best I could the hornet’s nest into which I feared I had fallen. At the word “Algeria”, which I could not avoid, his interest perked up. He left and returned in ten minutes. “Be on your way,” he said, “there is no record of a police intervention at 8, Rue Budé, nothing. There is nothing to it.” He dismissed me and nodded to the next supplicant.

I was not entirely reassured, but a weight lifted from me. I had demonstrated good intentions. The worst was over, I could resume my blameless life. I set out determinably in the direction of six o’clock, the exact opposite of my previous day’s exploration, crossing the river in a southerly direction. On Rue de la Bûcherie, no more than fifty paces from the bridge, I noticed a bookstore with English titles in its window. I was drawn to it, possibly by homesickness. There I browsed for half an hour before purchasing, with two American Express Travelers’ checks, Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. Also A Spy in the House of Love, by Anaïs Nin. Labelled as “Erotica”, the books were paired in a display, at 25% off. I took them in an act of courage that I could never have duplicated at home. Then I left the English bookstore and passed through clusters of students rushing hither and yon. Many were not much older than I. They were holding animated discussions, smoking, waving hands in the air. I walked on, feeling a painful social isolation. Then I came to a tall iron fence composed of metal spears, black with gold tips, surrounding an urban park so vast that its far side was invisible, blocked by crowns of trees. Unfolding my map to place myself, I found a thumbprint of green, Le Jardin de Luxembourg. From the nearest gate, one hundred paces down Rue St. Michel, I entered into a manicured promenade, tree-lined on both sides. Pascal must have walked here a thousand times, and played as a child. His father, if present, would have been aloof, staring at the sky. Mother and older sisters, hovering.

I walked deeper into the park, separating myself physically and psychologically from the incessant buzz of the city. I repeated to myself, in English, “the Luxembourg Gardens, the Luxembourg Gardens,” feeling those two consecutive hard g’s on my palate, drumbeating, syncopated. To my right was a chateau-like building, possibly a manor house for the grounds, but I was not attracted to it. Instead I turned to the left and followed a wide path that curved away to the southwest. Benches had been placed at intervals throughout the Gardens, punctuating the greenery of the lawns, the gravelled paths. I came to one that was unoccupied, dappled in half-sunlight. The bench’s seat was much longer than those we had at home, longer than the ones by Grenadier Pond, for example. In fact, these were long enough to stretch out upon and still leave room for others. But at that hour the park was sparsely populated. There was no competition for my place. I sat for two hours transfixed by The Tropic of Cancer, lost to Miller’s uncompromising prose, to a Paris I could only hope to know, sexual, transgressive, boisterous.

Past noon, a light rain began to fall. There was a café one hundred yards away, deeper into the park, with chalk-boarded prices. Resident pigeons patrolled the ground for crumbs, but as the place was nearly empty, irritation was evident in the way they bobbed their heads. As for the waiters, they were opening table umbrellas, talking among themselves. When they finally noticed me, I ordered and paid far too much for a tiny bottle of Orangina, a buttery croque monsieur. Then the rain accelerated to a downpour, and I half-sprinted from the Luxembourg Gardens, leaving by the same gate I had entered. Protecting my books by stuffing them under my shirt, I lowered my head against gusts of wind and ran back across the bridge.

At Rue Budé, my concierge made a strange gesture to me from behind her window, pressing two fingers of her right hand in a V against her left breast. Her lips moved too, but silently, incomprehensibly. To please her, I repeated her hand movements as best I could, and then I stooped to ask, “Has Pascal returned?”

“No, he was a dreamer, Pascal, a nice boy.”

A ridiculous thought then came to me, that she was an agent provocateur, planted by the police to draw me into some quagmire. I headed up the stairs to the drumming of rain in the courtyard. I resolved to become even more visibly apolitical. In the dim light of a brass lamp, I finished the Miller novel. Its profound effect upon me manifested itself later in the night when, awakening from a dream, I realized I was ejaculating into my underpants, my undershirt, into the bedclothes. I blushed from embarrassment even in the darkness of that unfamiliar bedroom, grateful to be unobserved, grateful that the police with their battering ram were not coming through the door. I heard only the low ticking of the clock in the hallway, a shout from the street. I tried to recapture the sexual imagery, whatever it was, but it was unreachable. In the morning I hand-washed my sullied clothes in the bathroom sink, hanging them just inside the open window to dry. Then I peeled an orange and separated it into segments. Juice spilled onto my fingers.

Enough of Henry Miller, of Anaïs Nin! I resolved to avoid the English bookstore and read instead from Flaubert, Stendhal, Proust, in the original. I would spend as little money as possible on food. I would live on cans of tuna fish, hard-boiled eggs, baguettes, the cheaper cheeses, fruit and vegetables. I would spend the remaining weeks of my exchange entirely in the sanctuary of the Luxembourg Gardens.

Down the stairs I tip-toed, hoping to avoid the concierge. “Young man!” she said, “please, deliver this for me!” She handed me a grenade-sized package heavily wrapped in brown paper. “Just around the corner, to my sister!” I could not refuse, though perhaps she had asked the same of Pascal. Perhaps he was innocent, a hapless fool, and she a master of deceit.

“Certainly, Madame,” I said. It was early, the street was empty. No one could possibly be watching. Whatever I was carrying was received matter-of-factly, two minutes later. Shed of that nervous responsibility, I hurried along the Seine until I came to the book-stalls. There I purchased a much-used copy of Madame Bovary and, checking over my shoulder first, I picked up a mimeographed pamphlet, The French in Algeria. The author’s name had been scratched out on the cover with a sharp instrument. On the title page, equally violently, his identity had been excised with a sharp knife or scissors, leaving a linear gap through which the word vérité could be seen. The bookseller raised his eyebrows, shrugged, and threw it in for free.

Satisfied, I set out for the Gardens. My bench was still vacant. I took a closer look at it, intending to describe it on a postcard. Of utilitarian design, it was constructed of a single horizontal plank, ten feet long and six inches wide, painted in forest-green. The back-rest was more spartan, a single two-by-four that pressed between the shoulder blades. The bench did not appear to be comfortable, but it was. Through aging, it bent under me slightly, like a hammock. To both sides were chestnut trees providing shade, leaves rustling in the breeze. I could be happy there, I knew, but first I should be practical. I should learn more about the political situation.

I put Madame Bovary aside and opened the damaged pamphlet. An hour later, my head spinning from acronyms—OAS, FLN, GPRA—I thought I had a basic grasp of the situation. France had invaded Algeria in the 1830s, had suppressed the Muslim population, had been accused of genocide. Resistance had predictably formed, violence had spread to continental France. French police were now being targeted as individuals, in and around Paris. War, in other words, was coming to the capital.

I realized that I had picked up an incendiary tract, its author an open supporter of the Communist Party. Leaving Flaubert face-down on my bench, I walked a hundred yards away and dropped the pamphlet into a waste container. Not mine, I would say, not mine. Then I returned to the novel and became absorbed by it, underlining sections in pencil. I was a student and this was my exchange, not with Pascal, not with his family, but with Flaubert.

Each morning after that I set out for the Luxembourg Gardens, waiting for my time in France to end. I settled eventually on the works of Proust, thinking him apolitical. September edged into October. The leaves of the chestnuts yellowed and fell. I carried a sweater with me, pulling it on and off as required. The office girls who came to the Luxembourg Gardens at lunchtime changed from micro-skirts to warmer, body-hugging attire. As usual, they sat on their own benches nearby, chatting, smoking cigarettes, eating sparingly from paper-bag lunches, paying no attention to me. The same could not be said of my concierge, who invariably jumped up from her station when, at the end of my day, I returned to the apartment. I would be lying if I pretended to remember her exact words, but they were always pointed. “Young man, you are a reader, you should know that Albert Camus is a traitor to the cause.” “They are killing policemen, and rightly so. Most of them were Nazi collaborators, the police, their sins washed clean by forgetfulness.”

Each morning after that I set out for the Luxembourg Gardens, waiting for my time in France to end. I settled eventually on the works of Proust, thinking him apolitical. September edged into October. The leaves of the chestnuts yellowed and fell. I carried a sweater with me, pulling it on and off as required. The office girls who came to the Luxembourg Gardens at lunchtime changed from micro-skirts to warmer, body-hugging attire. As usual, they sat on their own benches nearby, chatting, smoking cigarettes, eating sparingly from paper-bag lunches, paying no attention to me. The same could not be said of my concierge, who invariably jumped up from her station when, at the end of my day, I returned to the apartment. I would be lying if I pretended to remember her exact words, but they were always pointed. “Young man, you are a reader, you should know that Albert Camus is a traitor to the cause.” “They are killing policemen, and rightly so. Most of them were Nazi collaborators, the police, their sins washed clean by forgetfulness.”

I listened with apparent sympathy. I imagined Pascal doing the same, sealing his fate. “Yes,” I said, “yes,” and then I would mention the number of days I had left in Paris. I resold my Henry Miller to the bookstore but kept Anaïs Nin at my bedside. Mornings, I walked to the Luxembourg Gardens. I annotated Proust. I stretched out on my bench and fell asleep to the cooing of pigeons, the laughter of the shop-girls, the shuffling steps of old men. Cooler weather brought old soldiers out for a last gasp of air. Casualties of the first war, I assumed, amputees with canes, accompanied by nurses dressed in blue. They shuffled along together, eight or ten at once, shoes or slippers scuffing at crushed stone. I could taste the limestone dust on my fingers as I turned the pages. I observed the ancient warriors but I did not honour, in my heart, their sacrifice. I was distancing myself, preparing for home.

In the second week of October, knowing her time with me was limited, my concierge became even more animated in her commentary. “Young man, if you were dark-skinned, you would not be prancing about the city, carefree.” And the next evening, “The French National Police, our Gestapo, have imposed a curfew on all Algerian Muslims!” Finally, “There will be a protest march tomorrow, my Canadian friend, and if my husband were alive he would be at the epicentre, fist raised.”

It was more and more clear to me who the police should have arrested. I readied my suitcase for a quick departure, slipping my passport into my pocket. On the morning of my last full day, rather than head immediately for the Luxembourg Gardens, I decided to bookend my Parisian experience with a repeat trip to Sacré-Coeur. This time, as my pocket money had held out, I would pay for the funicular. I bought a larger sandwich, to share with the dog. I stood for five minutes beneath the gargoyles of Notre-Dame, this time noticing how eroded some of them were, pock-marked by acid rain. Then I crossed to the Right Bank but only made it halfway to my goal. A wall of policemen blocked every street. Beyond them I could see the home-made signs of Algerian marchers, slowly advancing. Signs in French against racism, signs in Arabic.

I turned on my heels, wanting no part of it. To dislocate me further, all the benches in my favourite area of the Luxembourg Gardens were taken, forcing me closer to the café. There I read throughout the afternoon. For lunch, I ate my dog’s portion of the sandwich, for dinner my own. The sun slipped low enough to cast long shadows, then dusk fell, then the cumulative exhaust of motor vehicles weighted down the air. Three black men ran past me, an unusual sight in the Luxembourg Gardens. They were headed in the direction of the river. I was reluctant to move but would have to follow them before long. I said goodbye to the pigeons not already gone to roost, to the bench that had welcomed me. Goodbye, Luxembourg Gardens. But some sort of melée was spilling back through the streets by the Seine. Sirens and flashing lights forced me away from the Pont St. Michel. Then there were two bodies on the street, smears of blood leading up to them as though they had been dragged there and dropped. Onlookers in clusters, not particularly concerned. They would have said the same of me, for I quickly sidestepped and made for the Petit Pont, one hundred yards to the east. From there I could see bodies being thrown from the Pont St. Michel to the river. I looked the other way. I picked up my pace to the apartment, past the cathedral again, the empty square, empty streets, another bridge, also empty. My concierge was gone too, and she was absent the next morning when I dropped the key on her desk.

In Toronto, my parents were alarmed and disappointed. Paris, the height of civilization. Pascal, not to our surprise, never showed up for his leg of the exchange. A decade later I realized—after the FLQ, after Baader-Meinhof, after Augusto Pinochet—that Pascal had acquitted himself much better than I, in the summer of 1961. He had stood up for, or been victimized by, a principle, while there I was, living in his stead, tending his father’s plants, reading Flaubert, reading Proust, marginally improving my French, shrinking into myself in the Luxembourg Gardens.

***

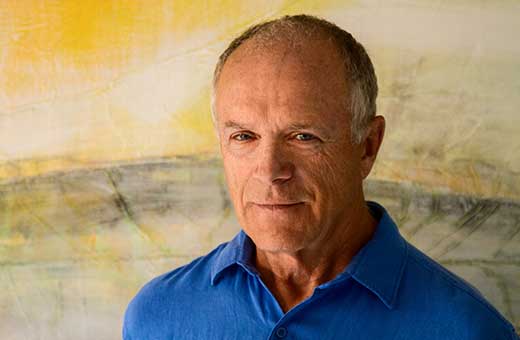

Nicholas Ruddock is a Canadian physician and writer. He has twice won the Bridport Prize, and has been shortlisted for the London Sunday Times Short Story Award in 2016. He was shortlisted 2020 for the Moth Poetry Prize. In Canada, his third novel Last Hummingbird West of Chile will be published in summer of 2021.

We’re a small group of volunteers, dedicated to writers, readers, and publishers. We’re also a paying market and do our best to champion all voices. When the nights are long and cold and the admin piles up, your help reminds us our work is appreciated. We’re hugely grateful for any support you can offer. Thank you.