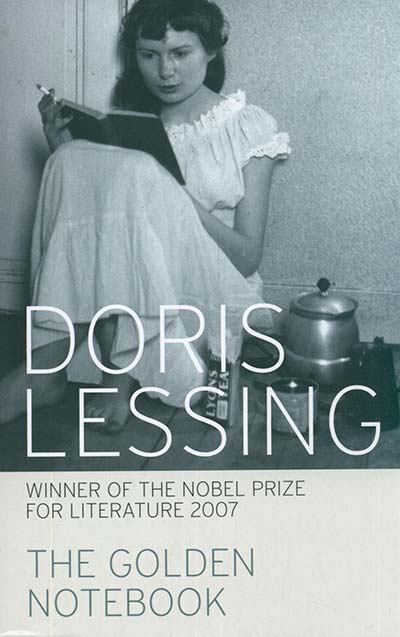

I came to Doris Lessing’s story ‘To Room Nineteen’ several years after reading her seminal novel The Golden Notebook. Originally published in Lessing’s short story collection, A Man and Two Women in 1963, the story takes place in 1960’s London.

I had read some of her other work, but The Golden Notebook had affected me in its portrayal of the female writer and the conflicts of her mind. In her short story ‘To Room Nineteen,’ Lessing develops this same theme, though the female protagonist is not a writer. She is one of hundreds of thousands of women who stopped work to raise a family in the so-called modern 1960’s, only to find themselves lost and invisible amidst the detritus of family life.

Lessing clearly had a nuanced understanding of the conflict arising between work and motherhood, to have covered it so often and succinctly. Awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2007, only the eleventh woman and oldest person to do so at that time, the awarding Swedish Academy described her as: “that epicist of the female experience”.

I was surprised to discover that ‘To Room Nineteen’ was written the year after the publication of The Golden Notebook. Being a child of the 1970’s and ‘80’s, I tend to think of the 1960’s as years of great changes and leaps forward in the emancipation of women. In the story, Lessing shows us a couple, Martin and Susan, who meet and marry, sensibly, we are told, a little later than their circle of friends, and this does feel like a modern marriage and meeting of minds. Both have decent careers and are portrayed as equals. They have four healthy children and that epitome of middle-class solidity, the large suburban house. So far, Lessing has portrayed a somewhat ‘golden couple’, and the reader can sense that it is only a matter of time before this ideal will come crashing down. It feels as though she overplays the perfection she describes in order to push to the forefront the argument that many may have that this women has nothing to complain about. Arguably, the narrator at the opening appears a little aloof and self-congratulatory.

I was surprised to discover that ‘To Room Nineteen’ was written the year after the publication of The Golden Notebook. Being a child of the 1970’s and ‘80’s, I tend to think of the 1960’s as years of great changes and leaps forward in the emancipation of women. In the story, Lessing shows us a couple, Martin and Susan, who meet and marry, sensibly, we are told, a little later than their circle of friends, and this does feel like a modern marriage and meeting of minds. Both have decent careers and are portrayed as equals. They have four healthy children and that epitome of middle-class solidity, the large suburban house. So far, Lessing has portrayed a somewhat ‘golden couple’, and the reader can sense that it is only a matter of time before this ideal will come crashing down. It feels as though she overplays the perfection she describes in order to push to the forefront the argument that many may have that this women has nothing to complain about. Arguably, the narrator at the opening appears a little aloof and self-congratulatory.

It was typical of this couple that they had a son first, then a daughter, then twins, son and daughter. Everything right, appropriate, and what everyone would wish for, if they could choose.

(p151)

We can taste Lessing’s heavy dose of irony here, as she tells us that the pattern followed by this couple is still what is the accepted norm of an ideal marriage in the early 1960’s. She does allow, however, that there is a certain ‘flatness’, and that the whole success of the marriage and perfect family life depends upon Matthew’s job and Susan’s ‘practical intelligence’ not allowing the whole to collapse. She gives us reason enough for this flatness: ‘But children can’t be a centre of life and a reason for being’, (p151). This appears to be the crux of the conflict as Lessing also makes remarks such as children not being a ‘wellspring to live from’, issuing a thinly veiled warning to women not to allow themselves to fall into this trap.

‘And she told him about her day (not as interesting, but that was not her fault), for both knew of the hidden resentments and deprivations the woman who has lived her own life – and above all, has earned her own living – and is not dependent on a husband for outside interests and money’.

(p152)

This reminded me that I had been naïve to conclude that the 1960’s had emancipated women, as I recalled as late as the 1970’s, women of my mother’s generation still often did not have their own bank accounts or savings, and were heavily reliant on their husbands for ‘housekeeping’.

To be fair to Lessing, she also points out that neither is Matthew’s job a reason for living, and though she moves into the mind-set and unravelling psyche of Susan, she does not condemn Matthew for allowing her spiral to happen, whilst even pointing out that he has had affairs. She presents their situation as a disintegration due to dissatisfaction: there are no villains in this piece. Neither is blame on the two of them apportioned, as Lessing points that it was not either of their faults that their love wasn’t strong nor important enough to support all that they have. It is unclear here whether Lessing is questioning the whole ideal of love as a concept to sustain the vagaries of a marriage, and that both parties need to be honest of this. Lessing reveals to us that though this couple are intelligent and have made wise choices and linked together voluntarily, they nevertheless represent many married couples of the time who were realising they could not be everything to each other.

It is as the children are going off to school that the chinks in this otherwise perfect façade are revealed. We witness Susan, formerly envisioning long days when the children were at school as a time of freedom for her to follow her own pursuits, falling into a kind of ennui, a dissatisfaction at the uselessness of her days. She must here have been echoing thousands of similar women’s voices, revealing a sense of emptiness. Lessing tells us quite heavy-handedly: ‘A high price has to be paid for the happy marriage with the four healthy children in the large white gardened house’, (p156).

She isn’t particularly missing the interaction with the children, however, as she begins to worry more about the way she is tied to the home, rather than free to do as she chooses. She reveals that small children are really boring to be with, which led me to wonder whether this would have been a novel idea at this time, when women were still expected to find fulfilment within the home. She feels that within another decade, she may return back to a woman with a life of her own, feeling that currently her soul is not her own, ‘As if the essential Susan were in abeyance, as if she were in cold storage’, (p156).

She begins to dread entering the house, and even more so the garden, once the children go to school, fearing there is an enemy waiting to invade her there. It seems this ‘enemy’ is fear, restlessness and emptiness. As her sense of ennui begins to descend dangerously lower, she even believes she sees a devil-like man waiting for her there. She realises she has not been alone in twelve years, and becomes obsessed by the idea of being quite alone for several hours a day, without any household or parental demands.

Although never descending to anything like these depths, I could connect with the character of Susan here on a real level. Re-reading the story when my eldest daughter was contemplating leaving for university, and even though I have continued to work part-time, I could associate with this feeling of uncertainty of who I was meant to be now. I, too, had experienced that sense of boredom at home with young children, whilst at the same time knowing I had been lucky to have the opportunity to choose this life. A conversation with other women about this life-stage revealed that this feeling was common, and it brought home to me just how relevant Lessing’s story was and still is.

As well as testing my beliefs of the freedom of women of this era, the reading of the short story, more so than Lessing’s novel, influenced myself as a writer in that I began to see that it was possible to show the conflict and often feeling of invisibility of women in society within a short story. Whereas The Golden Notebook had seemed like a wieldy and sophisticated novel in which Lessing could explore such fundamental ideas around women of the time, as well as social and cultural politics, her short story, though no less sophisticated, provided a much more succinct and available space in which to explore. I went away from the story with the knowledge that much could be achieved in small spaces, and published some of my own short stories and essays exploring themes of gender and feminism, invisibility and life choices.

As Susan begins to descend further down into a state of breakdown, her descent into madness reveals that she has come to feel a huge weight that the home, children and her husband’s wellbeing – even that of her cleaning woman – depend on her, yet cannot see what contribution she actually makes to it. She admits to herself that Matthew is just as depended on for his ‘voluntary bondage’, yet she questions herself as to why he does not feel bound. Perhaps Lessing was here raising the question of women’s guilt at their situation, that Susan should feel grateful for their lives rather than crave an impossible freedom from the life they have created. Or perhaps we are simply not given an insight into Matthew’s mind, where we may have found he felt as empty and unfulfilled as Susan. It is arguable here that Lessing is showing that although it appears that Susan has chosen this life for herself, it was in fact not a real choice given to women at the time, and perhaps that even if they felt they had made a free choice, they were perhaps unprepared for the limits this life would put on their own personality.

Susan initially has her own room designated as a place she must not be disturbed, but as her internal rage at being constantly available grows, she takes a room in a hotel three afternoons per week, where she simply sits, undisturbed, simply relishing in not being ‘Susan Rawlings, mother of four, wife of Matthew,’ (p171). She considers the roles she has played in her life up to this point, thinking nothing exists of her but the roles that go with her marriage and motherhood. To aid in her escape to Room Nineteen, she convinces an au pair girl to sit with the children, and appears to entertain ideas that in time the girl will take her place as Matthew’s wife and the children’s mother. Susan, feeling she does not exist without Room Nineteen, realises she has descended too deeply into this state of madness to turn back, and returns to Room Nineteen for the final time.

Lessing had famously criticised critics of her earlier novel The Golden Notebook for missing her essential theme of mental breakdown of her central character as a means of healing and freeing one’s self from illusions. Perhaps within this short story she attempted to revisit this idea, with devastating consequences for Susan.

Lessing had famously criticised critics of her earlier novel The Golden Notebook for missing her essential theme of mental breakdown of her central character as a means of healing and freeing one’s self from illusions. Perhaps within this short story she attempted to revisit this idea, with devastating consequences for Susan.

‘To Room Nineteen’ has echoes of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, in its portrayal of the consequences of women not having their own independent means nor access to outside interests. Though Lessing did not consider herself as writing feminist fiction at the time. One of Lessing’s contemporaries, Margaret Drabble, wrote of Lessing’s work entering the realm of ‘inner space fiction’ exploring mental and societal breakdown. In this story, we see a much more personal exploration of one woman’s breakdown than in her famous novel, dealing as it did with social and cultural politics, as well as personal issues. But I think it is the short form which allowed Lessing to explore this personal breakdown so efficiently and succinctly, and confirms her as one of the truly great writers, short or otherwise, of the 20th Century. The issues she probes within this story and her other work continue to be explored by other women writers, and readers, the world over.

***

Kate Jones is a freelance writer, yoga lover and coffee drinker from the North of England. Her work has appeared in various online & print journals including The Short Story, The Nottingham Review, Spelk, Feminartsy and The Real Story. Links to her work can be found at writerinresidenceblog.wordpress.com

Support TSS Publishing by subscribing to our limited edition chapbooks