Rental Hearts, Lion Lovers and Girlfriends in the Deep Freezer: Magical Realism and the Contemporary Short Story in the UK

*

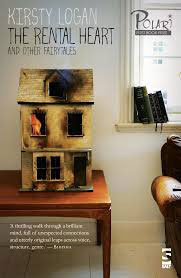

The last decade has seen a renaissance of the short story in the UK, and within this, magical realist narratives have been rife. This list is far from exhaustive, but short story writers using magical realism include: Ali Smith in, for instance, The First Person and Other Stories (2008), which includes a tale of a Guardian-reading woman who finds a cherubic-looking baby in her Waitrose trolley, which turns out to speak like a sexist, racist Al Murray type; some of Sarah Hall’s work, including ‘Mrs Fox’, awarded the 2013 BBC Short Story Prize, in which a woman turns into a fox to her husband’s dismay; Scottish writer Kirsty Logan’s The Rental Heart (2015), winner of the Polari Prize 2015, which features fairy-tale rewritings, teenagers with tiger tails, and coin-operated boys; Daisy Johnson’s collection Fen (2016), awarded the 2017 Edge Hill Prize, which includes stories of human-animal transformations; Krishan Coupland’s work, such as ‘The Sea in Me’, Bare Fiction Short Story Prize winner 2016, a tale of a talented teenage swimmer who is also part mermaid; Melanie Whipman’s Llama Sutra (2016), the title tale of which features a woman impregnated by a llama; Speak Gigantular (2016) by London-based Irenosen Okojie, which has stories of suicides haunting the London Underground and thumbprint photos multiplying of their own volition; and Rebecca Lloyd, such as her ‘The Lobster Woman’s Luck’ in The View from Endless Street (2014), about lobster fishing and love on the remote isle of Marraday.

What the term ‘magical realism’ means can be confusing,[i] but loosely it refers to: odd or magical events appearing in an otherwise realist story, one that takes place in our own world or one recognisably like it; and the magical events being taken as an ordinary or natural part of life, often without comment. Kirsty Logan’s ‘Coin-Operated Boys’ begins with the observation, delivered in a matter of fact tone: ‘That August, Elodie Selkirk became the latest lady in Paris to order a coin-operated boy’. In Rebecca Lloyd’s ‘The Lobster Woman’s Luck’, when Mainland Mary throws Double Steve’s newly ironed shirt out the top window of her shop straight at him, it lands at his feet still folded; she then flings a mug of tea out the window and it lands bottom down, not spilt and still steaming, next to the shirt.

Magical realism is distinct from fantasy fiction in that it doesn’t engage in world-building; and while magical elements may give characters unusual qualities, such as the circus performer Fevvers’ wings in Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus (1984), they do not presuppose a supernatural force in the world, magic, that can be harnessed by privileged individuals like Harry Potter or Merlin. Rather, the supernatural is naturalised; the codes of the ‘supernatural’ and ‘real’ co-exist but are given equal weighting and a degree of authorial reticence or irony enables this.

But in what ways and why have short story writers been drawn to magical realism recently in the UK? The short story is a brief, intense form that seems appropriate to the chaotic, fragmented, time-pressurised modern world; at its best, it creates concentrated worlds with an emotional impact, demands intelligence and reflection from the reader, and rewards re-readings. I want to suggest that magical realist narrative modes lend themselves well to short fiction. If, as William Carlos Williams says, the short story acts like the flare of a match struck in the dark, magical realism as an ingredient makes the flame more luminous and memorable. Many of the short story writers discussed here see the label ‘magical realism’ more as marketing ploy by publishing companies than as something they self-identify with; certainly, it is true that calling a book ‘magical realism’ helps sales – it is a commercially successful genre – but the stories I discuss do show key features of this kind of fiction. I have been fortunate to interview a number of these writers in the past couple of years and will draw on their own words to illustrate my points.

At the simplest level, magical realism is popular as it grants a way of telling good, inventive stories. Who doesn’t enjoy priests levitating after they drink hot chocolate, sassy teenagers with tiger tails, cups of tea that are thrown from a window and land on the ground without spilling a drop? Within the short story, magical realism can engender vivid detail too, one key to the success of this kind of fiction. In Kirsty Logan’s ‘Una And Coll are not Friends’, the teenage schoolgirl Una has ‘bloody great antlers stretched a foot out of the top of her head….She’d wrap coloured scarves around them and hang necklaces off the curly ends’ (p.63). In Krishan Coupland’s ‘The Sea in Me’, the teenage protagonist, a brilliant swimmer but also, it seems, part mermaid or fish, has ‘froggy webs between my toes’ as well as green hair that ‘floats around my head like a coral reef plant and turns with me, follows me slender and obedient like a tail’.[ii]

The magical elements – some original, some recomposed from the encyclopaedia of human experience that is myth – signal to the reader that that anything can happen, that, if nothing else, the story won’t be predictable; the suspension of disbelief needed to pull off successful magical realism might be easier in a short piece; and the short story form may allow a writer to try out ideas in a way they might not be prepared to in a novel – as Irenosen Okojie has said, ‘it is a form that enables me to experiment and be fearless.’[iii] Importantly, too, incorporating magical or mythic aspects in this way doesn’t preclude the story being seen as serious literature. Unlike what it unfairly called ‘genre fiction’ – science fiction and fantasy – magical realism has made it firmly into the canon of ‘literary fiction’; magical realism makes the shortlist of prestigious novel and short story prizes, with the Booker of all Booker’s being Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (1989), a canonical magical realist text. Given the proliferation of short story prizes and collections in the UK in the past decade, I don’t think this cultural acceptance of magical realism as ‘literary’ can be ignored when considering why so many writers are turning to it.

The magical elements – some original, some recomposed from the encyclopaedia of human experience that is myth – signal to the reader that that anything can happen, that, if nothing else, the story won’t be predictable; the suspension of disbelief needed to pull off successful magical realism might be easier in a short piece; and the short story form may allow a writer to try out ideas in a way they might not be prepared to in a novel – as Irenosen Okojie has said, ‘it is a form that enables me to experiment and be fearless.’[iii] Importantly, too, incorporating magical or mythic aspects in this way doesn’t preclude the story being seen as serious literature. Unlike what it unfairly called ‘genre fiction’ – science fiction and fantasy – magical realism has made it firmly into the canon of ‘literary fiction’; magical realism makes the shortlist of prestigious novel and short story prizes, with the Booker of all Booker’s being Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (1989), a canonical magical realist text. Given the proliferation of short story prizes and collections in the UK in the past decade, I don’t think this cultural acceptance of magical realism as ‘literary’ can be ignored when considering why so many writers are turning to it.

Read our interview with Irenosen Okojie.

Magical realism also allows themes to be explored in a way that may be both more direct and, surprisingly, more subtle than in realist fiction; and this may appeal to short story writers with far less word-count than novelists for thematic musings. In Ali Smith’s ‘The Hanging Girl’ (from Other Stories and Other Stories, 2004), Pauline finds a girl hanging from a lamppost, cuts her down and takes her home to look after her, but the girl keeps hanging herself on household objects (a tree in the garden, the kitchen clock, ceiling lights), when she is not watching quiz shows on television, that is. The story raises questions about whether Pauline is suffering delusions, but the hanging girl is also an embodied, concrete metaphor for fears she has about global events witnessed on television, like public hangings and death camps, as well as for feelings she has about her own life and mortality: ‘every one of us [is] falling through air with one end attached to our birthdates until the rope pulls tight.’ (p. 27)

Scottish writer Kirsty Logan’s beautifully crafted collection of short stories, The Rental Heart and Other Stories, uses magical realist techniques in a similar way. In ‘Una and Coll Are Not Friends’, Coll, who has antlers, and Una, who has a tiger’s tale, find themselves attracted to each other, despite Una’s ostensible hostility to her ‘freakish’ teenage classmate; and in ‘The Rental Heart’, the protagonist, having had her heart broken, rents a metal heart when she meets Grace, to protect her from further emotional pain. Logan has noted: ‘Many of the stories in my first book developed as a literal exploration of a feeling or thought. For example, I had my heart broken and thought, rather melodramatically, as you do when you’ve been dumped, “This hurts so much that I wish I could take out my heart and get a new one”. And so ‘The Rental Heart’ came to be…. My dad was an alcoholic, and we never seemed to speak about it, and when we did speak about it the words never came out right – there was ‘Bibliophagy’… As a teenager I often felt like an outsider, so strange and awkward in my skin, as if I had antlers or a tail – and there’s ‘Una And Coll Are Not Friends’’.[iv] Logan’s metaphors may be literal, but this does not make them simplistic or blunt; there is elegance and subtlety to her imagery, just as there is to her language. Una’s antlers and Coll’s tiger tail allow the writer to explore the complex and individual emotional responses to what it feels like to be different as a teenager.

Recording human experience through the structures of magic and wonder is something fairy tales and folk tales have always done. Italo Calvino, the masterful 20th-century writer whose style changed from observational realism to fabulous fiction after his contact Italian folktales, insisted that ‘folk tales are real’. That is, they speak of human truths, of poverty, oppression, anxiety, lust, love, greed, envy, cruelty, kindness, triumph over adversity, domestic conflict. Calvino, who fought Fascism and was a communist, saw fantastic fiction as the literature of ‘the people’ whom he wanted to reach and represent. He described how his own fiction ‘fell under Perseus’,[v] a reference to the Greek mythic hero who avoided the petrifying gaze of the Medusa by looking at her via the reflection on his shield; if Medusa represents gazing into the dark heart of reality, an experience which can paralyze, then the Perseus figure of the writer doesn’t abandon reality but approaches it indirectly, giving free range to the imagination. Magical realist short story writers, too, ‘fall under Perseus’. As Liska says in Logan’s A Portable Shelter (2017): ‘There is no other way to give you the truth except to hide it in a story and let you find your own way round inside’ (p. 102).

Many writers who use magical realism acknowledge the influence of myths, fairy tales and folk tales, forms that are rich in symbolism as well as porous, open to reworking. The Rental Heart and Other Stories includes fairy tale retellings that put female experience and sexuality at their core; in this way, Logan sits within the contrary tradition of the feminist fairy story that started with Angela Carter’s (1979) Burning Your Boats. In Logan’s ‘Witch’, the Russian fairy-tale figure of Baba Yaga is revamped in a contemporary setting. We first hear of Baba Yaga as a rumoured witch living deep in the woods, a scary and fascinating bogeyman that local girls talk about to frighten each other. There is a grain of truth to this – a woman with heart-red curls does dwell in a log cabin in the local woods. She fled there when she was evicted from her flat and lost her girlfriend; and she has ‘sewn stories around herself; a shroud of children’s nightmares to protect her from the world’ (p.76). The protagonist of the story, a young woman from a similarly precarious background, finds the log cabin by chance; when invited in, a sexual and emotional revelation follows. ‘I crawled towards her on the bed….She was the poison apple, the kiss that would wake me. When she finally slid inside me, I knew the end of my story…. I knew what happily ever after was and I wanted to be a wicked witch too’ (p.81).

Many writers who use magical realism acknowledge the influence of myths, fairy tales and folk tales, forms that are rich in symbolism as well as porous, open to reworking. The Rental Heart and Other Stories includes fairy tale retellings that put female experience and sexuality at their core; in this way, Logan sits within the contrary tradition of the feminist fairy story that started with Angela Carter’s (1979) Burning Your Boats. In Logan’s ‘Witch’, the Russian fairy-tale figure of Baba Yaga is revamped in a contemporary setting. We first hear of Baba Yaga as a rumoured witch living deep in the woods, a scary and fascinating bogeyman that local girls talk about to frighten each other. There is a grain of truth to this – a woman with heart-red curls does dwell in a log cabin in the local woods. She fled there when she was evicted from her flat and lost her girlfriend; and she has ‘sewn stories around herself; a shroud of children’s nightmares to protect her from the world’ (p.76). The protagonist of the story, a young woman from a similarly precarious background, finds the log cabin by chance; when invited in, a sexual and emotional revelation follows. ‘I crawled towards her on the bed….She was the poison apple, the kiss that would wake me. When she finally slid inside me, I knew the end of my story…. I knew what happily ever after was and I wanted to be a wicked witch too’ (p.81).

Angela Carter quipped that, in rewriting fairy tales and myths, she wanted to put new wine in old bottles to make the old bottles explode. Melanie Whipman’s clever, engaging Llama Sutra, which includes magical realist and realist stories, continues the subversive feminist tradition. She is drawn to the short story form as it ‘presents both a microcosm and magnification of life’[vi]. In ‘After the Flood’, a reworking of the biblical myth, Noah and Mrs Noah have settled back onto land, planted a vineyard, but Noah is angry and surly, and Mrs Noah is restless and suffering domestic violence. On the ark it was she not Noah who better weathered the storms and long periods of waiting; and on the ark, too, she took the male lion as her lover. She has now admitted as much to her husband. ‘Forgive me, Noah, for I have sinned’, although privately she is aware it didn’t feel like a sin and still yearns for the lion: ‘That honeyed side beneath my thighs and the dandelion down of his stomach.’ Whipman is sensitive to the gender issues in fairy tales and myths: ‘Most were originally written in massively patriarchal societies. The female protagonists tend to be passive and powerless. I love tapping into these communal narratives, taking myths and fairy tales and giving them a contemporary twist. In most cases this means creating strong, independent female protagonists. I also think that yoking a modern woman’s views with ancient myths creates a sense of universality and emphasizes our narrative heritage.’[vii]

Read our interview with Melanie Whipman.

Whipman’s observations are pertinent. Magical realism has long been associated with voices overlooked or ‘othered’ by a dominant culture, whether those of women, minorities, migrants, rural communities, or indigenous people. As D’haen (1995) observes, ‘It is precisely the notion of the ex-centric, in the sense of speaking from the margin, from a place ‘other’ than “the” or “a” centre, that seems to me an essential feature of … [what] we call magic realism.’[viii] Before magical realism became a popular global phenomenon, it was first associated with 20th-century writers like Gabriel García Márquez and Miguel Ángel Asturias. They set out to incorporate the folk wisdom, indigenous beliefs and popular narrative techniques of Latin America into the European modernist literary form, to create a quintessentially Latin American literature. As Zamora and Faris (1995) note, ‘Texts labelled magical realist draw upon cultural systems no less ‘real’ than those upon which traditional literary realism draws – often non-western cultural systems that privilege mystery over empiricism, empathy over technology’.[ix] In Men of Maize (1949), perhaps the most anthropologically informed novel of all time, Miguel Ángel Asturias found inspiration in Mayan and Aztec sources as well as in Guatamalan folklore. He depicts a reality that realism simply isn’t adequate to describe: the voice of the Earth calling to the protagonist Gaspar Llom, the curses of firefly wizards proving efficacious, the postman Nicho Aquino shape-shifting into a coyote. Warnes (2009) calls Asturias’s strain of magical realism ‘faith-based’ – that is, it uses magic to expand and enrich pre-existing concepts of the real, granting access to and validating cultural modes of perception that have been overlooked or even lost.

Warnes distinguishes this faith-based magical realism from a more secular and sometimes knowing kind – ‘irreverent’ – although he acknowledges both kinds may be present to some degree in all magical realist stories. Irreverent magical realism, which began appearing in the UK in the 1970s and 1980s with writers like Salman Rushdie and Angela Carter, doesn’t so much provide access to a more mythic way of seeing as elevate magical events to the same status as the real in order to ‘cast the epistemological status of both in doubt’ and ‘critique claims to truth and coherence in the modern world’.[x] This sort of magical realism often attaches itself to specific cultural or historical discourses that a story tries to undermine or question, such as patriarchy or racism. In Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus (1984), a journalist constantly questions whether the aerial circus performer Fevvers’s wings are natural or a concocted illusion; through this, Carter meditates on gender – is it biological or culturally constructed? In Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses (1988), the magical elements are used to explore the impact of migration on individual characters and the communal experiences of minority cultures living in 1980s London. When Saladin, an Indian migrant to London, metamorphosises from man to devil, complete with horns and a tail, he asks how this can be possible and receives the enlightening reply, ‘They [the police and associated institutions] describe us… that’s all. They have the power of description and we succumb to the pictures they construct’ (p.168). Within the multicultural metropolis, Rushdie shows, there are competing views of the world, but this contest is unequal. Because within magical realism the nature of the real, the believable and the normal, simply cannot be taken for granted, Rushdie sees this as a useful narrative mode for undermining dominant discourses, celebrating cultural heterogeneity and hybridity, and giving those ‘othered’ a voice. Rushdie has said he is a writer for whom ‘the processes of naturalism in fiction have not been sufficient’.[xi]

Daisy Johnson may not share the playful tone of Rushdie, but her accomplished, haunting collection of short stories, Fen (2016), does use magical realist techniques to give a voice to rural East Anglian women, and to question ideas about gender and nature. Set in the Fens, a realm of stark landscape reclaimed from the sea and small provincial towns where the pub is always the Fox and Hounds, her stories feature a girl who morphs into an eel, a dead man who comes back to his wife and mother, young women who lure men home from the pub and feast on them, and the mother of a messianic man who feeds off words and memories in her mind. The author approaches the strange events with a matter of fact tone and sturdiness of detail: women feasting on men may be a fairy-tale theme, but after they have done so in the story ‘Blood Rites’, the young women eat toast and paint their nails; and in time, too, the kind of phrases used by the men they’ve eaten (‘Fucking Jesus’, ‘What the fuck?’) start to come from their own mouths – ‘I think they are inside us,’ the protagonist says. Johnson has said that she is attracted to the strangeness, brevity and beauty of short stories; and the magical realism within them ‘often begins as strength for the female characters (they can breathe underwater, they eat men) and gradually seems to turn against them. Magical realism is used as a way to undermine old orders, to create new realities and new possibilities. It is the fiction of attack. It says look this way and then, behind your back, changes everything you thought you knew. It also creates a space where these women characters can speak out loud, can become more than their relationship to men’ (my italics).[xii]

Daisy Johnson may not share the playful tone of Rushdie, but her accomplished, haunting collection of short stories, Fen (2016), does use magical realist techniques to give a voice to rural East Anglian women, and to question ideas about gender and nature. Set in the Fens, a realm of stark landscape reclaimed from the sea and small provincial towns where the pub is always the Fox and Hounds, her stories feature a girl who morphs into an eel, a dead man who comes back to his wife and mother, young women who lure men home from the pub and feast on them, and the mother of a messianic man who feeds off words and memories in her mind. The author approaches the strange events with a matter of fact tone and sturdiness of detail: women feasting on men may be a fairy-tale theme, but after they have done so in the story ‘Blood Rites’, the young women eat toast and paint their nails; and in time, too, the kind of phrases used by the men they’ve eaten (‘Fucking Jesus’, ‘What the fuck?’) start to come from their own mouths – ‘I think they are inside us,’ the protagonist says. Johnson has said that she is attracted to the strangeness, brevity and beauty of short stories; and the magical realism within them ‘often begins as strength for the female characters (they can breathe underwater, they eat men) and gradually seems to turn against them. Magical realism is used as a way to undermine old orders, to create new realities and new possibilities. It is the fiction of attack. It says look this way and then, behind your back, changes everything you thought you knew. It also creates a space where these women characters can speak out loud, can become more than their relationship to men’ (my italics).[xii]

Read our interview with Daisy Johnson.

Irenosen Okojie, born in Nigeria but resident in the UK much of her life, also writes dark, inventive stories from the perspective of women, though in her case it is young, black urban women. Speak Gigantular, her remarkable first book of short stories, includes various genres including magical realism. ‘In ‘Walk with Fear’, two ghosts of suicides, called October and Haji, roam the London underground, trapped in that place. October and Haji talk about their lives and deaths, but also wander and play; they stand on top of Circle Line tubes ‘pretending to be airplanes’; on the District Line, they hold onto passengers’ coattails and laugh when the people try to get through ticket machines with them in tow. Such vivid, playful images within bleak stories are a trademark of Ojokie’s; loss and loneliness are common themes. Okojie has observed: ‘Most people will look at Speak Gigantular and see a bunch of weird stories. This is true, although Speak Gigantular is partially a response to the invisibility and erasure that young black girls and black women in general experience in this country…. These experiences are multiple, never-ending, subtle and overt…. Since I didn’t see myself reflected enough in fiction and the world around me generally, since I love books, I decided to carve a space for myself, for girls and women who look like me, but I wanted to do it in ways that are unexpected so the reader is challenged on multiple levels, so a transformation occurs’.[xiii] This echoes Melanie Whipman’s observation: ‘I want the reader to be as unsettled as my protagonist; magic realism can facilitate this’.[xiv]

Given the ubiquity of magical realism in novels and short stories, I should briefly ask just how radical or alternative this narrative mode really is. Within magical realism scholarship, opinions are divided about its progressive impulse; some have praised the form for being a ‘new multicultural artistic reality’, while others, like the critic Jean Franco, have seen it as ‘little more than a brand name for exoticism’.[xv] Some of this tension between the progressive and exoticising impulses of magical realism is succinctly expressed by short story writer Crista Ermiya (author of the excellent The Weather in Kansas, 2015), who was born and raised in London with Filipino and Turkish-Cypriot heritage; she says that magical realism offers a ‘means of expressing cultural heterogeneity … and that is definitely an instinctive draw for me. But on the other hand, I don’t really like the idea of non-western being the equivalent of the mythical – although I’m certain I do it/have done it myself.’[xvi] Certainly, the most sensitively charged of these debates concerns the representation of non-western or indigenous cultures in this literature, which is not at stake with most of the authors cited here. What is more, many of the stories I have mentioned are ones that address themes like identity, difference, gender and marginality in ways that unsettle cultural complacencies and give pause for thought.

Read our interview with Crist Ermiya.

The commingling of the weird and the everyday, rooting this in grounding detail, is something Krishan Coupland does, too, in his engrossing, often disquieting short fiction. When Patrick’s girlfriend comes back from the dead the day after her funeral in ‘Days Necrotic’ (from When You Lived Inside the Walls, 2017), he ‘carried her downstairs to the treasure-chest freezer in the garage. There she slept, on top of a wad of blankets, surrounded by the bags of frozen peas and chicken chunks and hanks of fish coated in ice, the dial cranked all the way to blue’ (p.12). The couple make love, during which Patrick experiences a ‘pain like glass’ when he orgasms, and the next day his skin is cracked and reddened. Coupland appreciates the craft and intensity of the short story form. He doesn’t describe his as a ‘fiction of attack’, but does see it as connected to alternative fiction. ‘I was an avid reader [as a teenager], but had never encountered anything quite like the literature I found online. It was energetic and weird and different. I think up until that stage I had only really encountered short stories from centuries ago, and while I’d enjoyed them, they never spoke to me in the same way that the stuff I found online did. I wanted to make that kind of writing part of my life, to be involved with it’.[xvii] I think Coupland makes a useful point here: easy access to all genres of fiction via the web may be a reason younger writers are drawn to composing non-realist kinds, including magical realism.

Read our short story with Krishan Coupland.

All the short story writers I have talked about in this essay blend magical with realist elements in a seamless manner to create fresh, compelling short fiction that offers digestible vignettes of the human condition. The stories all reward re-readings and leave the reader musing on the vivid images and complex metaphors and meanings within them. Cynthia Ozick said that, while a novel takes the reader on a journey, the short story is more like the talismanic gift given to the protagonist of a fairy tale – something whose power is not fully understood but that can be tucked into the pocket, taken through the forest on the dark journey. I would suggest that, by using magical realism, short story writers make their talismanic gift to the reader especially potent, a jar of fireflies flashing in the dark, to light a pathway through the forest of human experience.

***

K.T.Wimhurst is a writer who has been published in numerous magazines and anthologies. She has a particular interest in magical realism and surrealism.

Footnotes

[i] For discussions about the history and definition of the term see Bowers, M.A. (2004) Magic(al) Realism, London: Routledge, and Warnes, C. (2009) Magical Realism and the Postcolonial Novel: Irreverence and Faith, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

[ii] http://www.barefictionmagazine.co.uk/2016/05/fiction-sea-krishan-coupland/

[iii] Wimhurst, K. (July 2017) ‘Interview with Irenosen Okojie,’ https://www.theshortstory.co.uk/the-short-story-interview-irenosen-okojie/

[iv] Dastur, R. and Wimhurst, K. (February 2017) ‘Interview with Kirsty Logan,’ https://www.theshortstory.co.uk/the-short-story-interview-kirsty-logan/

[v] Calvino, I. ‘Memo on Lightness,’ in Calvino, I. (1988) Six Memos for the Next Millenium, Harvard: Harvard University Press.

[vi] Wimhurst, K. (May 2017) ‘Interview with Melanie Whipman,’ https://www.theshortstory.co.uk/the-short-story-interview-melanie-whipman-2/

[vii] Ibid.

[viii]D’haen, T (1995) ‘Magical Realism and Postmodernism: Decentring Privileged Centres’, in Parkinson and Faris (eds) Magical Realism: Theory, History, Continuity, Durham: Duke University Press, p.194.

[ix] Zamora, L.P. and Faris, W. (1995) ‘Introduction’, in Parkinson Zamora and Faris (eds) Magical Realism: Theory, History, Continuity, Durham: Duke University Press, p.3.

[x] Warnes, C. (2009) Magical Realism and the Postcolonial Novel: Irreverence and Faith, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.13-14.

[xi] Ibid p.98.

[xii] Wimhurst, K. (September 2017) ‘Interview with Daisy Johnson,’ https://www.theshortstory.co.uk/the-short-story-interview-daisy-johnson/ [my italics].

[xiii] Wimhurst, K. (July 2017) ‘Interview with Irenosen Okojie,’ https://www.theshortstory.co.uk/the-short-story-interview-irenosen-okojie/

[xiv] Wimhurst, K. (May 2017) ‘Interview with Melanie Whipman,’ https://www.theshortstory.co.uk/the-short-story-interview-melanie-whipman-2/

[xv] Warnes, C. (2009) Magical Realism and the Postcolonial Novel: Irreverence and Faith, London: Palgrave Macmillan, p.1.

[xvi] Wimhurst, K (January 2018) ‘Interview with Crista Ermyra,’ https://theshortstory.co.uk/the-short-story-interview-crista-ermiya/

[xvii] Wimhurst, K. (March 2017) ‘Interview with Krishan Coupland,’ https://www.theshortstory.co.uk/the-short-story-interview-krishan-coupland/

References

Bowers, M.A. (2004) Magic(al) Realism, London: Routledge.

Calvino, I. (1988) Six Memos for the Next Millenium, Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Dastur, R. and Wimhurst, K. (February 2017) Interview with Kirsty Logan, https://www.theshortstory.co.uk/the-short-story-interview-kirsty-logan/

D’haen, T (1995) ‘Magical Realism and Postmodernism: Decentring Privileged Centres’, in Parkinson and Faris (eds) Magical Realism: Theory, History, Continuity, Durham: Duke University Press.

Wimhurst, K. (September 2017) Interview with Daisy Johnson, https://www.theshortstory.co.uk/the-short-story-interview-daisy-johnson/

Wimhurst, K. (July 2017) Interview with Irenosen Okojie, https://www.theshortstory.co.uk/the-short-story-interview-irenosen-okojie/

Wimhurst, K. (March 2017) Interview with Krishan Coupland, https://www.theshortstory.co.uk/the-short-story-interview-krishan-coupland/

Wimhurst, K. (May 2017) Interview with Melanie Whipman, https://www.theshortstory.co.uk/the-short-story-interview-melanie-whipman-2/

Warnes, C. (2009) Magical Realism and the Postcolonial Novel: Irreverence and Faith, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Parkinson Zamora, L. and Faris, W. (1995) ‘Introduction’, in Parkinson Zamora and Faris (eds) Magical Realism: Theory, History, Continuity, Durham: Duke University Press.