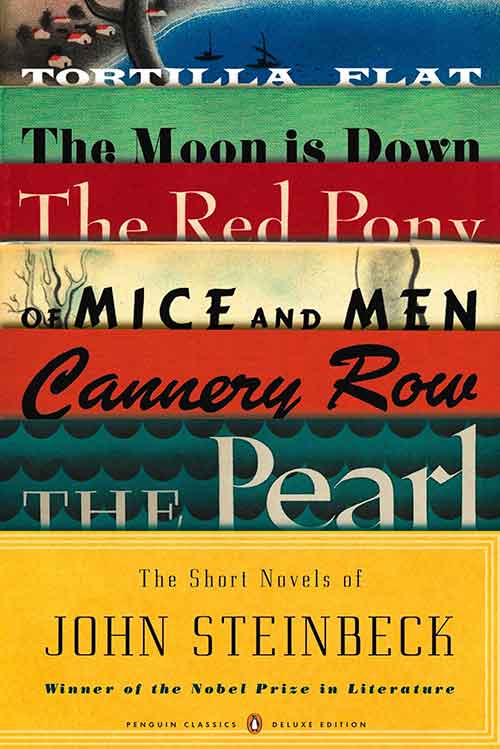

In the Penguin compilation volume, The Short Novels of John Steinbeck (2009 [1953]), the six novels chosen – the word novelette is used to describe one of them– half could be viewed as long short stories, and it is through the lens of the short story form that I tend to view them. Whereas Cannery Row and Tortilla Flat have that multiplicity of characters, plots and sub plots, and the sense of a wider setting that the novel – or novella and novelette – demands, stories like The Pearl, The Moon is Down, and Of Mice and Men, have the focus, unity and singularity of the short story. They might have the length, but they do not have the breadth of even a short novel. At just over 82 pages, Of Mice and Men bears comparison with D.H.Lawrence’s St Mawr, which is longer, and The Captain’s Doll, which is only a few pages shorter, and both of which are in his The Tales of D.H.Lawrence (1914), described as ‘his shorter fiction’ in the preliminary ‘Note’. The reference highlights the difficulty we have with labelling stories in the gap between an obvious 5,000 word short story, and an obvious 60.000 word novel.

In the Penguin compilation volume, The Short Novels of John Steinbeck (2009 [1953]), the six novels chosen – the word novelette is used to describe one of them– half could be viewed as long short stories, and it is through the lens of the short story form that I tend to view them. Whereas Cannery Row and Tortilla Flat have that multiplicity of characters, plots and sub plots, and the sense of a wider setting that the novel – or novella and novelette – demands, stories like The Pearl, The Moon is Down, and Of Mice and Men, have the focus, unity and singularity of the short story. They might have the length, but they do not have the breadth of even a short novel. At just over 82 pages, Of Mice and Men bears comparison with D.H.Lawrence’s St Mawr, which is longer, and The Captain’s Doll, which is only a few pages shorter, and both of which are in his The Tales of D.H.Lawrence (1914), described as ‘his shorter fiction’ in the preliminary ‘Note’. The reference highlights the difficulty we have with labelling stories in the gap between an obvious 5,000 word short story, and an obvious 60.000 word novel.

Of Mice and Men has no scene, either in its prose fiction form or in the play-script, where at least one of the two leads is not present, and in most scenes both are. In a novel one expects to find scenes without the ‘lead’ character, where minor characters enact or discuss issues not directly connected with the lead character’s story arc. In fact, a hallmark of the novel is the unfolding of other stories against which the story of the lead character, or characters, can be compared and contrasted. This is where the loose ends, which novels often have to tie up after the climax of the story, come from, loose ends that are rarely, if ever, encountered in a short story. There are no loose ends in Of Mice and Men.

*

I started to read side by side, the short story, and play-script versions, and to highlight the changes. Reading the play I was struck by how ‘word for word’ it seemed to be. Narrative elements of the text had been converted into stage directions, and some direct speech lifted intact

The process of switching from play script to prose fiction or vice versa is one I’ve attempted myself. Sometimes a short story could seem so heavy in dialogue, and so light in narrative that I slipped into writing a play instead. Once or twice, where the dialogue was sparse, an attempted script became a short story. The two forms lie close together. Arthur Miller, a master of both, mentions the exchange in his preface to the short story collection: Presence.

He calls the short story ‘this form of art in which a writer can still be as concise as his subject requires him to be.’ Of the play, by contrast , he refers to ‘the theatrical tone of voice, which is always immodest…’ Of dialogue specifically, he makes the comment:

I… find dialogue much harder to write in a story than in a play…..The spoken line is a ‘speech’, it is something said to a crowd……This ….is why it is impossible to lift scenes of dialogue and put them on the stage.

Which last, is of course, precisely what Steinbeck appears to have done, and very successfully. I’d love to find out what Miller thought of Steinbeck’s adaptation, but as yet have been unable to!

The opening two pages of script in my Joseph Weinberger edition of the play bring me to the end of page three in the Penguin edition of the written story. A page and a half of prose description has been reduced to a third of a page of stage direction. A page, in smaller print, of general notes about the setting and structure, has gone before, but Steinbeck’s short story narrative has formed the basis of the stage directions, borrowing a few phrases, compressing some, leaving some out – notably the descriptions of his characters.

Over the following page and a half of play-script whole speeches are kept intact or changed by only a word or two, with some additions and a few deletions. They are not merely recognisably the same exchanges, but seem, without close comparison, exactly the same.

GEORGE: (irritably) Lennie, for God’s sake, don’t drink so much. (He leans over and shakes LENNIE.) Lennie, you hear me! You gonna be sick like you was last night.

(LENNIE dips his whole head under, hat and all. As he sits on bank, his hat drips down his back.)

LENNIE: That’s good. You drink some, George. You drink some too.

(Steinbeck, play, 1943)

Or, put a similar way:

“Lennie,” he said sharply, “Lennie, for God’s sakes don’t drink so much.”

Lennie continued to snort into the pool. The small man leaned over and shook him by the shoulder. “Lennie. You gonna be sick like you was last night.”

Lennie dipped his whole head under, hat and all, and then he sat up on the bank and his hat dripped down on his blue coat and ran down his back. “That’s good,” he said. “You drink some, George. You take a good big drink.” He smiled happily.

(Steinbeck, prose fiction,1937)

One could continue the exercise through the entire play, and it would show similarly. The stage directions echo the descriptions of how things are said and what is done. They fill in the ambient mood created by Steinbeck’s paragraphs of scenery. Here’s a Steinbeck prose description from the middle of that first scene:

The day was going fast now. Only the tops of the Gabilan mountains flamed with the light of the sun that had gone from the valley. A water snake slipped along on the pool, its head held up like a little periscope. The reeds jerked slightly in the current. Far off towards the highway a man shouted something, and another man shouted back. The sycamore limbs rustled under a little wind that died immediately.

We can find a stage direction at the same place in the play:

(The light is going fast, dropping into evening. A little wind whirls into the clearing and blows leaves. Dog howls in the distance.)

No mention of the Gabilan Mountains, needed to locate a short story, but not the play, which is located in front of us. When I find examples like this, I’m reminded of the idea that a story exists in itself, and that the tellings, or showings of it are separate from it, being reflections upon it, or reports of it.

There is something here about who we, as readers, think is telling the story. When we watch a story on stage or screen we willingly or otherwise, suppress our knowledge that it is not really taking place, and ‘believe’ we are observing it. With a story told in text, or read aloud to us, we practice no such deception, but imagine – create images in our minds – according to our understanding of the words – which will not be simply their dictionary meanings, but their meanings specifically to us as individuals. But how aware are we, in either format, of the teller of the tale, or even of its creator?

In the short story form we have the direct speech, and the narrative – which might include reported speech as well – but in the case of the play or screen version, that narrative has been communicated only to the director and the actors and might have been ignored by them. Even where stage directions are played out, they are not ‘told’ to the audience, and if they were in some experimental way, they would become part of the ‘direct speech’ of the actors.

*

In the case of Steinbeck’s tale his two characters do and say pretty much the same, and so do all the other characters of the cast, and what the audience gets to see, on stage or screen, replicates, or perhaps replaces, what the reader or listener must imagine. I mention ‘screen’ for there are ‘screenplays’ of the story -two, as it happens, filmed in 1939 and 1992.

In the case of Steinbeck’s tale his two characters do and say pretty much the same, and so do all the other characters of the cast, and what the audience gets to see, on stage or screen, replicates, or perhaps replaces, what the reader or listener must imagine. I mention ‘screen’ for there are ‘screenplays’ of the story -two, as it happens, filmed in 1939 and 1992.

Is there also a difference between play-script and screenplay?

My thought is that there is, but that there is also a similarity. Both forms give us the direct speech directly. In that sense we are dependent for our understanding and reaction to them as words, in whichever format we experience them. There is an obvious qualification here though, for the words spoken to us by an actor may be more powerfully or more subtly expressed. A single reader might do a good job, but even if he or she ‘puts on’ different voices, it will leave more to our imagination than does the presentation of a speaking character on stage or screen. When we read to ourselves, silently or aloud, it is we who have to become the actor, and give our best performance, but we only have those printed words, of speech, and of narrative commentary on it, to go on. The written story is open to our imagination. For the shown story, film is a specific version, but the play has the possibility of interpretation – equivalent to the imagination of the solitary reader, right up until the moment of its performance.

The big difference between short story and both play or film, is the replacement, or replication, of what we are being asked to imagine, by what we are being compelled to see. If Lennie has blue eyes on stage or screen, it’s no use you having imagined them as being brown. And when Curley’s Wife is a brunette in both films, you can’t really maintain that imagined blond who Steinbeck gave us in both the short story and the play-script.

There are other differences between the play and the film forms. The play, as Arthur Miller has suggested, is a method of staging speech, never mind that we watch it as well, but film tips the balance firmly in the direction of observation, and away from the interpretation of words.

In the 1992 film adaptation (Dir. Gary Sinise) there are some clear examples of this, such as the opening shots, in which images from the back-story of George and Lennie are shown: a distressed girl in a torn red dress runs across the fields towards working men. Lennie and George are shown running from pursuers. They are shown hiding in the irrigation ditch – an image recollected later in the story by George in both short story and play-script – and then jumping a freight train – something not in the short story at all! Subsequently, George’s recollections from the short story are not required in the film.

Another example is the small detail towards the end of the film where the ‘stable buck’ is shown passing his rifle to Carlson, this despite the fact that, lifted almost word for word from the short story, Curley has told Carlson to get the stable buck’s gun.

Perhaps the explanation is that where information is complex in words, but simple in visuals, the words are not needed, but where the words are concise, the film-maker slips in a reinforcing image, just in case we haven’t been paying attention. Could it be that visual people don’t trust language? Surely it is not that they don’t trust pictures?

A subtle use of language in both forms, is where Candy confesses to George that he should have shot his own dog, foreshadowing George’s shooting of Lennie at the end, and perhaps, as is signalled by a close-up glance in the film, putting the idea into his head.

At the end of the 1992 film the post-shooting arrival of the posse, and particularly of Slim, who understands more deeply than any of the other workers the relationship between George and Lennie, and the nature of Lennie himself, has been entirely omitted. The film ends, first on George’s face, as he rides a box car – a shot used previously over the opening credits, and not featured, even by implication, in the told story – and finally on the image of George and Lennie walking side by side into a middle distance; the parody of a riding off into the sunset trope.

Steinbeck’s play-script ends at the instant of the shooting of Lennie. Lennie’s last words are ‘I can see it!’ followed by the stage direction ‘(GEORGE Fires. LENNIE crumples, falls behind the brush. Voices of men in distance.)’ His short story ends on the comment, as George and Slim walk away: ‘Now what the hell ya suppose is eatin’ them two guys?’

Here are three distinct endings, and each one giving us a closing image to observe, or imagine: each one, perhaps, raising a different question, and demanding a different answer as we reflect on the story we have been told, or shown.

The earlier film version (Dir. Lewis Milestone, 1939) adds other questions and prompts other answers, allowing us to make other comparisons, and to think about other similarities and differences. It too begins with the back-story escape, including that irrigation ditch, and uses the freight train. A nice literary touch is that when George (Burgess Meredith) pulls closed the box car door he reveals the full quartet of Burns’ lines from which Steinbeck culled his title.

The bus journey is used too, and it is on the bus that George and Lennie begin their conversation, whereas in the told story the bus journey is recalled in later conversation. The film even adds a short altercation between George and the bus driver. Curiously, Lennie pets a bird, rather than a mouse, and George’s rant about being better off without him mentions a pool room, but not a cat house!

In all four versions though, George and Lennie dream of a home, and a work load that can be set down at their wish, and a friend who can be put up for the night. These were, perhaps, the dreams of working people, and still might be for many of us.

If you want to understand how stories operate, comparison of the different tellings and showings of the same story can be useful. When the same speeches are used, are they in the same order? And if not, why not? In the 1939 film there is no Vaseline glove, no cat house, nor any legs for Lennie not to look at (though there is a pair for us). Why are some speeches cut? Why are new ones introduced? Compare what happens in each version between, for example, Carlson leaving the bunk house with Candy’s dog, and the sound of the gunshot. There are thirty two lines of prose in my edition of the short story, and six speeches by various characters in the play-script. The 1939 film follows this passage very closely. But we can ask what, in the play, and films, is done in words, and what with other elements? And which words do it? And which words do the work in the short story, and what do the wordless elements do in the other formats? The play stage direction says ‘After a long silence, a shot in the distance’ echoing the short story’s ‘A shot sounded in the distance.’ Follow the filmed scene, and you can match it, the speech word for word, the actions by the lines of prose and of stage direction, seeing as you do, the exact words of the short story that do to our imaginations what the film and play must offer for our observation.

More generally we can ask, are new ideas introduced? Or is it that existing ones are more heavily underlined? In the 1939 film there are many extra scenes, and small additions to existing ones. Curley’s Wife is given a name here, and we have several new scenes showing details of her life, even one of her taunting Curley with her knowledge of the truth about his crushed hand. Was it the words of the original that the film makers had no faith in, or their own relatively new techniques (many of which, Eisenstein reminded us, were invented by D.W.Griffith as a result of reading Dickens! – in Film Form, Harcourt,1977, Dickens, Griffith, and the Film Today)? Why did Milestone show us George stealing Carlson’s gun? Was it because he doubted we would understand what had happened otherwise, when George produced it on the river bank? And what difference does it make that George shows Slim that he has it before they set off to find Lennie, implying a collusion between them that wasn’t apparent to me in the short story. The film’s ending is very similar to that of the short story, but makes Slim an accessory before the fact rather than one after it! Steinbeck’s odd last line, though, is missing in all three adaptations. In the short story, it is Carlson who asks ‘Now what the hell ya suppose is eatin’ them two guys?’, a question that the written original alone asks, demands even, that we attempt to answer. Is it that words leave us with unasked questions to speculate about and reflect upon, whereas shown stories have to make sure we have seen what there is to see?

Here’s something useful too, about the writing process, and also, perhaps, about the difference between a story that is to be observed and one that is to be imagined. For the narrative words, the non-direct speech, in a told story must be imagine-able. Those words must communicate to the reader, or listener, at least some of what the director and actors will add to the spoken words when presenting their film or play.

The writer, unlike the film maker, but not wholly unlike the playwright, must give us the background, the foreground, the actors and the action, and a sense of how all those words are to be spoken, heard and reacted to. The writer can, and must, be selective about how much of each of those elements he or she makes plain, and how much will be left to the imagination – a luxury, and a responsibility that the film maker, and to a lesser extent the play director does not have.

The writer can tell you ‘the man walked down the street’, and you can perfectly well imagine it, but the film maker has to clothe him, build the street, add in the background and anything else that might be within sight, add the ambient sound, and even decide upon the weather, even when those elements have no direct function in the story, or parallel in the text being adapted.

What does get left out of the play, or film script, and isn’t converted to stage direction, are short passages of description that run through the story. This begs the question of what it is that a play has that a short story does not, and why what is unnecessary for the former is necessary for that latter.

My guess would be that the presence of the actors and the stage set provides a continuous context within which the speech will be heard. In a told story, by contrast, the background is continually renewing and refreshing as the story, told one word at a time in order, shifts its focus towards and away from the fore-grounded characters, their speeches, thoughts and actions. We imagine intermittently and episodically, that imagination being sparked by our response to words, individually and in groups. Those passages of description return us to the background context which in the case of the play or film is always present, in the props, flats, lighting and soundtrack.

And why, in both film versions, but not in the play, does the event at Weed, the pursuit and escape, have to be shown right at the beginning, and not come out only as recalled back-story later? It must be something to do with expectation of the audience’s ability to follow the plot. The similarity of what is added to the story in both versions is also interesting. The train is wholly new, the bus journey referred to in the original, but expanded upon in both films. Is what we might imagine and add to the text ourselves being imagined for us? Or is it something to do with the timelessness of imagination, compared to the measureable duration of movies? In both movies there are lingering shots of the inter-wars agricultural process, the steam driven threshing machines, mule-drawn carts, and hard labour. Look for them in the short story, and you simply will not find them.

Something you will find in the novel is totally absent from the other three versions, and that is Lennie’s hallucination near the end, in which he is lectured, not only by his late Aunt Clara, but by a large, imaginary rabbit. Could it be that such a fantasy in our imagination – the told story – does not affect the powerful realism of the story, but in a play or film – the shown story – would destroy it utterly and at the very moment of its climactic scene. Curiously, the earlier of the two films introduces an element of comedy, albeit a bitter comedy, in those added scenes between Curley and his wife. She has been given the name May, and is thus humanized more than in the other versions. Their relationship is examined, and also their family life. In particular the scene where she watches Curley and his father eat, greedily and without pleasure – I was reminded of the father in H.E.Bates grim story The Mill – takes the tragedy of her life to the level of comic absurdity. The musical soundtrack here underwrites that it is meant to be comic.

The tight focus of the short story, on conversations which take place mostly in-doors, does not need the expansion of character study, landscape, and working-life backgrounds. It uses brief introductory descriptions to set a tone and context, which is picked up by the descriptions of how those conversations are conducted, and topped up, where necessary, as at the end, where we re-visit the waterside camp-site of the opening scene.

Recognising these elements in both forms, and the way in which they are replicated or replaced tells us not only about the relationship between the differing forms of storytelling, but also helps us to understand the way in which each forms works. Direct speech is ‘inside’ the story in a way that narrative is not. Narrative qualifies and instructs our imagining of that speech in the case of the told story, as the tone of voice, volume, tempo and accompanying actions do in the shown one. This difference is the main reason why I am so wary of the simplistic advice to writers to ‘show not tell.’ Words can only tell, and must do so by triggering our own understanding and response to them.

Taking a story like Of Mice and Men, and separating out the direct speech from the rest can be instructive in itself. How much of the story might we get from either part, for example? But when we can make the comparison with the shown form, of play and film, of the same story, the lessons become more interesting. We begin to see that a story is made up not only of what the characters say, but of what the story teller reveals to us of what he or she has created as a context for those words, and of their motivations and purposes. Each element illuminates the other: speech, commentary, description. In the film and the play the latter two obviously support the provision of the first, but in the told story the unity of story, and of language, which is all we have, might distract us from the different jobs being done by those three elements. Sometimes, we might say, it can be difficult to see the writing for the story.

What makes the study of this story and its adaptations so interesting to me, is that it is clearly a tale that more than fifty years after its first appearance remains tied to its original agenda, an agenda still relevant, powerful and totally comprehensible. Even some side issues, such as the treatment of negroes, and of women, are treated in a way that we could recognise as being sympathetic. Neither the play, nor the films tries to superimpose a new, or even revised narrative point of view.

***

Brindley Hallam Dennis writes short stories. He lives on the edge of England. Blogs at www.Bhdandme.wordpress.comand writes poetry,plays and essays as Mike Smith.

Support TSS Publishing by subscribing to our limited edition chapbooks.