Why should I care about setting in my stories? I always skip long descriptive passages, they’re boring.

If that sounds like you, if you’ve ever had the ghost of that thought – listen up. You need setting and you need it to be good in a short story because setting transports the reader to your world. It’s a vital tool in invoking the reader’s dreamtime with you. Good writing gives the reader the confidence to enter the fictional trance of the story and not wake up until the writer allows it.

The objective is to impart tone, mood and world-build and as ever, for short stories it must be done succinctly and early on; hopefully also with style, whatever style is relevant to the story, and perhaps also with grace. Something other than a brusque blob of indigestible description. How do you do setting briefly? How do you get that single brush stroke that says Horse in a way which is more classical Chinese than Constable or Stubbs? Because in a short story you want the essence of the thing, not necessarily the hay and the hedgerows as well.

It depends on the style of your story is one answer.

One method is to get it over and done with as quickly as possible. You can give a time and a place and leave it at that. Provided the reader has a frame of reference, it will carry the story some distance, so long as all other details such as clothes, technologies, dilemmas and preoccupations are in line with this basic parameter.

London. 1984.

Trenches, 10th November 1918

Even a Star Date will do it.

This may be all you can allow yourself if it’s microfiction you’re dealing with. Or, a few well-chosen specific details can be enough:

‘Scalpel.’

The blade glinted in the harsh lighting, the respirator continued its relentless rhythm, her scalp prickled with sweat.

And we’re off.

But how do the stars do it?

Some authors let the reader become aware of the world in which the story takes place more subtly. In ‘The Lottery’, Shirley Jackson sets the scene of rural village life with one preoccupation, giving us a false sense of security. She gives us the date but not the year. She uses eighty words to portray a community, a scenario of the ‘universal’, and in fair weather. The outlook is positive – isn’t it?

Some authors let the reader become aware of the world in which the story takes place more subtly. In ‘The Lottery’, Shirley Jackson sets the scene of rural village life with one preoccupation, giving us a false sense of security. She gives us the date but not the year. She uses eighty words to portray a community, a scenario of the ‘universal’, and in fair weather. The outlook is positive – isn’t it?

‘The morning of June 27th was clear and sunny, with the fresh warmth of a full-summer day; the flowers were blossoming profusely and the grass was richly green. The people of the village began to gather in the square between the post office and the bank, around ten o’clock; in some towns there were so many people that the lottery took two days and had to be started on June 26th, but in this village there were only about three hundred people.’

The reader is hooked and transported to that village.

Hemingway – famously succinct, transports us to a trout stream in a few words. The extract is from ‘Now I Lay me’, which is about a soldier with post-traumatic stress who is afraid of the dark and can’t sleep so he occupies his mind with memories of trout fishing as a boy. The story is six pages long with only three paragraphs about the fishing, but the fishing remains with the reader throughout the story. So how is it done?

First Hemingway evokes the experience of fishing on a river in terms that bring out the river itself, with a medium lens. No panning round the surrounding countryside, no fish, no bait or hooks yet.

I would think of a trout stream I had fished along when I was a boy and fish its whole length very carefully in my mind; fishing very carefully under all the logs, all the turns of the bank, the deep holes and the clear shallow stretches, sometimes catching trout and sometimes losing them. I would stop fishing at noon to eat my lunch; sometimes on a log over the stream; sometimes on a high bank under a tree, and I always ate my lunch very slowly and watched the stream below me while I ate.

That’s 96 words – for some, job done. We’re there by the river, we can get on with writing about the action now. But to make it stick, Hemingway works the scene a little more. Whilst still building on the setting but now in close-up, he brings out the things a boy would focus on, adding the childhood angle without explicitly saying anything at all:

Sometimes I found insects in the swamp meadows, in the grass or under the ferns, and used them. There were beetles and insects with legs like grass stems, and grubs in old rotten logs; white grubs with brown pinching heads that would not stay on the hook and emptied into nothing in the cold water. (55 words)

The third paragraph has a combination of wide angle lens and close up.

Sometimes the stream ran through an open meadow, and in the dry grass I would catch grasshoppers and use them for bait and sometimes I would catch grasshoppers and toss them into the stream and watch them float along swimming on the stream and circling on the surface as the current took them and then disappear as a trout rose. (60 words)

In many ways this can be seen as a carefully constructed list of all the things associated with trout fishing, but there are also elements of threat and the macabre which relate to the soldier’s state of mind. Notice also the variations in sentence length, which flow with the stream and takes its time for lunch and the number of harsh glottal ‘g’ sounds in the insect section. Because of the specific details and the tone of the description, the experience feels very believable, the reader is certain the narrator has done this as a child and so allows the fictional dream.

In ‘Tomorrow Is Too Far’, Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche gives us a garden in Nigeria that places the reader firmly within an arena of abundance and heat. Again, it’s a kind of list.

In ‘Tomorrow Is Too Far’, Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche gives us a garden in Nigeria that places the reader firmly within an arena of abundance and heat. Again, it’s a kind of list.

‘Grandmama’s yard felt moistly warm, a yard with so many trees that the telephone wire was tangled in leaves and different branches touched one another and sometimes mangoes appeared on cashew trees and guavas on mango trees. The thick mat of decaying leaves was soggy under your bare feet. In the afternoons, yellow-bellied bees buzzed…’

Taken from the collection The Thing Around Your Neck.

Kazuo Ishiguro opens and closes his collection of five stories, or fictional musical movements entitled Nocturnes, with stories set in St Mark’s Square in Venice. The narrator in each case is a musician playing for tourists.

The first short story ‘Crooner’ opens like this:

The morning I spotted Tony Gardener sitting among the tourists, spring was just arriving here in Venice. We’d completed our first full week outside in the piazza – a relief, let me tell you after all those stuffy hours performing form the back of the café, getting in the way of customers wanting to use the staircase. There was quite a breeze that morning, and our brand-new marquee was flapping all around us, but we were all feeling a little bit brighter and fresher, and I guess it showed in our music.

‘Cellists’, the fifth story and final story opens with character, setting and mood all in one sentence although it’s only fair to say we are returning to the Piazza in Venice, a setting which has been established in the opening story.

It was our third time playing the Godfather theme since lunch, so I was looking around at the tourists seated across the piazza to see how many of them might have been there the last time we’d played it.

Here the reader is transported to Venice but it is the experience of being there with these characters that is important. St Mark’s Square is inferred, ‘the piazza’ is shorthand for all of the tourist experience of architecture and history – the reader fills it all in for himself.

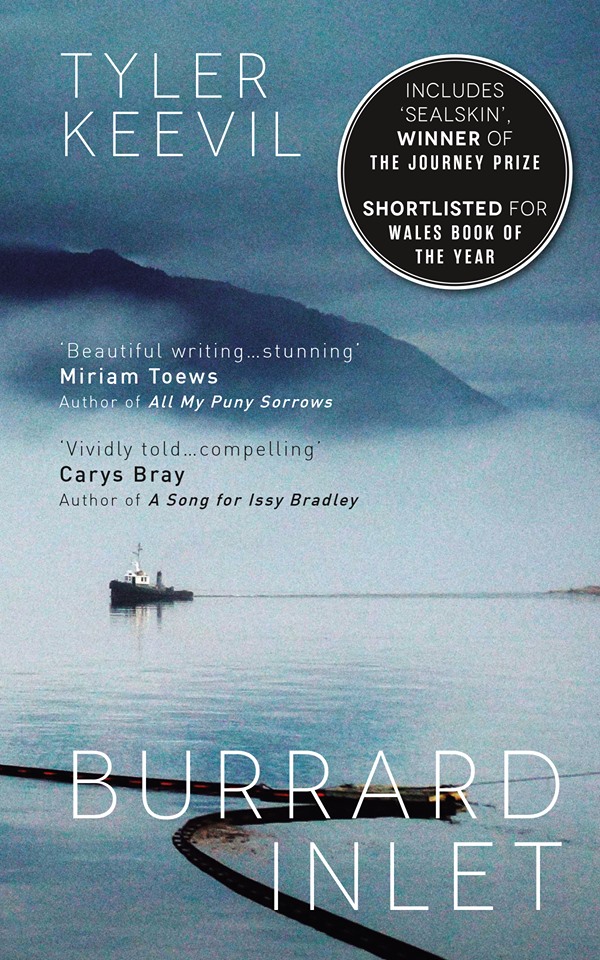

Canadian writer Tyler Keevil now lives in Wales. Set in Canada, his short story collection Burrard Inlet is remarkable in many ways but particularly for his extraordinary evocations of place. I asked him about the importance of place and setting in his writing. His answers demonstrate the professionalism with which Keevil approaches setting as an aspect of his work. Do not be fooled by the modesty – this is powerful writing, all the more interesting because of the rugged settings combined with contemporary male preoccupations, often domestic and personal. On that note, I also asked him about his views on ‘conflict’ in his writing.

The stories in Burrard Inlet are skilfully executed and interesting to unpick because the settings or locations are always used to enhance the story (‘Edges’) but in many, the setting is also the story (‘Scrap Iron’, ‘Carving Through Woods’ on a ‘Snowy Evening’).

Can you say how you conceive the setting or think about place during the process of writing?

Place is very important to me; it’s possibly the most important element. I tend to draw on real locations, and visit and research them like a locations scout might, in filmmaking. So almost all of the settings in Burrard Inlet are actual places, which I then use as a backdrop for a fictional narrative. Though sometimes, as in filmmaking, you have to ‘cheat’ a bit too.

I want to say that many of these stories could only happen in this place but it’s not true because many of them are the epitome of the particular being universal (especially ‘Snares’, ‘Mangelface’, ‘Shooting Fish in a Stream’ – actually all of them). So I feel that the stories could only happen in this way, in this place – ‘Sealskin’ particularly comes to mind.

I want to say that many of these stories could only happen in this place but it’s not true because many of them are the epitome of the particular being universal (especially ‘Snares’, ‘Mangelface’, ‘Shooting Fish in a Stream’ – actually all of them). So I feel that the stories could only happen in this way, in this place – ‘Sealskin’ particularly comes to mind.

How conscious are you of this universality being grounded in your specific place?

Do the two aspects arise together or you have one before the other and bring them together?

Joyce Carol Oates said ‘elevate to the universal’ and I understand how important that is, but I don’t tend to think about that while writing. I agree these stories could only happen in these particular places. I’d also say that you can’t separate character from place. Like any organisms we’re partly products of our environments: social, geographical, climatological.

Where the importance of location is concerned, is there a difference between the stories that are stronger social commentaries such as ‘Sealskin’, ‘Snares’, ‘The Art of Shipbuilding’, and the others?

That’s a tricky one, in part because I didn’t consciously set out to include social commentary in any of the stories (though of course looking back I understand what you mean). But no, I adopted the same approach to location in all of the stories, regardless.

Many of the stories relay the strong impression of being autobiographical, which may have a bearing to your answers above.

In relation specifically to place, if we consider ‘Carving Through Woods on a Snowy Evening’ – how important is writing what you know?

Those luminous descriptions of following the lost rider’s trail will stay with me a long time and if you tell me you can’t snowboard, I may not believe you.

Writing what you know is crucial, but I try not to cling to the truth; Plath said you need to be able to manipulate experience with an informed and intelligent mind, and that’s something worth striving for (though I make no claim to being either informed or intelligent). ‘Carving’ is an interesting one because it’s probably the least autobiographical of the pieces. I love snowboarding and do know that mountain well, but I’ve never worked as a search and rescue volunteer or ridden through the backcountry at night (which would be crazy).

‘Reaching Out’ is a journey and ‘There’s a War Coming’ could be set in many cities – they are grounded in the same location but can be easily envisaged elsewhere. The setting is not quite incidental but is also not as vital in these stories. Is there a reason for this? Were they conceived in a different time and place from the other stories?

I always envisioned ‘Reaching Out’ as being set on Mount Seymour, and entrenched in that location and culture; I see it as a companion to ‘Carving’ and ‘Edges’. ‘There’s a War’ does have a different feel – I had to cheat that location from a restaurant in downtown Vancouver to one on the inlet, so perhaps you picked up on that!

Specifically regarding writing short stories: How do you evoke the sense of place in such a short space, using as few words as possible? ‘Fishhook’ is a great example of a very short story with clear and concisely evoked place.

Do you consciously use a distilled format?

Both great questions, but unfortunately I don’t have a real key or secret: for me it’s largely an intuitive process. I would say, though, that because I’m writing about places that exist, I don’t feel compelled to over-describe in order to convince the reader of their reality. I don’t need to: they are real. I suppose it comes down to a kind of belief in the location that allows you to choose the right details.

You don’t always give the setting in the opening of the story, which I find surprising because the settings are so important and the sense of place so strong. In ‘Carving Through the Woods on a Snowy Evening’ and ‘Shooting Fish in a Stream’, the characters start in one place and move location, although the mood or tone is set at the beginning of the story.

Are tone and mood related to setting and place for you and if so – how do you use them to create a sense of place?

I recall an early reader telling me I should cut the beginning of ‘Carving’ since the real story starts with the emergency phone call, and the drive up the mountain. But sometimes you get the impulse to resist a ‘well-made story’ and I loved the idea of opening at a tedious party and then completely surprising readers by taking them on this life-and-death rescue mission. I would say that yes, tone and mood are related to setting, though I think it works both ways: the sense of place can help create the tone and mood, as well as vice versa.

Do you feel you are communicating something of an insider’s view to the outside world? How much was that a motive for writing these stories?

I think that’s a very valid point and I teach my students that you have an advantage when you can provide that ‘insider’s view’ as an author, but in the case of Burrard Inlet I don’t see that as a major motivation. When I was writing the stories I didn’t necessarily envision them as part of the same collection: they were drafted over a decade or so, along with many others. When Parthian commissioned a collection I began to sift through all the stories I’d written, and these ones seemed to come together and coalesce.

Did you conceive or write these stories when you were no longer physically in that place or did you have to be there to write them?

How has your own physical change of location affected your writing? Your novel Fireball is also set in Canada – will you continue to write about Canada?

All the stories were written after I’d left Vancouver, and was away from those locations – so that is probably more of a motivating factor. In a way, I’m rebuilding an imaginative version of the landscape I left behind, out of homesickness, nostalgia, and a yearning which, I’m told, equates to a kind of ‘hiraeth’ – a Welsh word that has no exact English translation. I think I’ll always be drawn back, and write about home, but I’m writing about Wales now, too.

Leaving aside prose style for now, for me, the main reason your stories are compared to writers such as Hemingway and Carver is in the robust muscular concept of the conflicts – these stories are masculine (small ‘m’) approaches to universal, but masculine situations. However, they are far more accessible to female readers than Hemingway’s stories have been considered.

Also, the protagonists are not aggressively male – your protagonists are sympathetic modern men.

The question about accessibility is very interesting. Perhaps the difference comes down to worldview, rather than any savvy awareness of the potential reader on my part. Masculine attitudes and codes of conduct can be pretty questionable, and a lot of what goes on under the guise of machismo does not sit well with me, and never has. In that respect I like to think I’m more aligned with Steinbeck’s humanism. I love Cannery Row and Sweet Thursday, and the idea of that coastal community he depicts.

Where the antagonist is another male (‘Edges’, ‘There’s a War Coming’, ‘The Art of Shipbuilding’, ‘Tokes From the Wild’) the antagonists are of a type which the male protagonist must try to overcome without resorting to the enemy’s tactics – such as bullying or physical aggression.

How far is this related to location and setting? Is there an economic element to this aspect – in relation to the local industries and opportunities?

There may be an element of that, and the protagonists are often from a different social background, but I’d be cautious of drawing firm conclusions based on class or economics. For example, Roger, the skipper in the barge triptych, is a stern taskmaster but he is also somebody the narrator greatly admires and respects. In a way he’s a foil for Rick, in ‘Sealskin,’ who is bullying and sadistic. You see that reflected in their attitudes to nature: Roger frets about protecting the ducks, whereas Rick, well – he does what he does. Both come from a similar background, but they are strikingly different people.

Where the antagonist is nature, the protagonist often finds a softer (more modern) approach to the conflict. In ‘Carving’, the protagonist literally goes with the flow of the elements yet wins in the end because he has taken from or absorbed sublimity from the place and elements and they have not diminished him.

In ‘Tokes’, the protagonist overcomes the physical difficulties by changing himself rather than imposing himself on the landscape.

That’s a fascinating interpretation, which I hadn’t thought of – but it sounds good to me. In ‘Tokes’, especially, the story is about adapting to a new and more rugged environment. In ‘Carving’ he is definitely attuned to the mountain, though from another perspective he is also taking unnecessary risks, which is pretty questionable behaviour for a rescue volunteer. He manages to pull through, but only with the help of those who are doing their job properly.

Finally, what writers have influenced your writing of short stories?

Most of the ones mentioned above, I suppose, though I always hesitate to claim those giants as influences. But if you asked me which short story writers I love, I’d say Oates, Carver, Hemingway, Munro, Mansfield, Chekhov, MacLeod…also, there are lots of contemporary Welsh and Canadian short story writers I admire: Rachel Trezise, Eden Robinson, Steven Heighton – too many to list, really.

***

The author is grateful to Tyler Keevil and Parthian Books for their help with this article. Tyler Keevil has written two novels but continues to work in the short form, details of which are on his website here.

Tamsin Hopkins writes poetry and fiction. Her collection – Shore to Shore, river stories was longlisted for the Edge Hill Prize in 2017, is a set text on the UH Creative Writing BA and is published by Cinnamon Press in paperback and e-book for kindle. Her poetry pamphlet Inside the Smile was published in July 2017, also by Cinnamon Press. Find her at Tamsinhopkinswriter.com or facebook and on Twitter @TamsinHopkins

Please help support TSS Publishing by donating here or subscribing to our limited edition chapbook series here.

Please note that TSS Publishing may earn a small commission from Associate Links and adsense.