Review by Sarah Evans

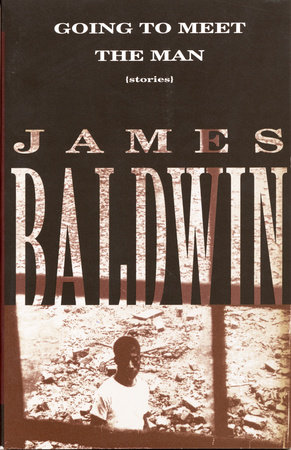

Publisher: Penguin Modern Classics (1991, first published 1965)

Publisher: Penguin Modern Classics (1991, first published 1965)

256 pages

RRP: £12.00

ISBN: 0140184495

When asked by a TV interviewer about the challenges he faced starting his writing career as someone ‘black, impoverished, homosexual,’ James Baldwin’s response was to laugh and say, ‘I thought I’d hit the jackpot.’ He continued, ‘It was so outrageous you could not go any further. So you had to find a way to use it.’

In his writing – both fiction and essays – Baldwin did exactly that, drawing intimately on his own life to describe the experience of being black American and to depict gay love in a way it had rarely, if ever, been portrayed before.

Baldwin was born in Harlem in 1924 and never knew his biological father. His mother married when he was three and he was brought up, in extreme poverty, by her and David Baldwin, the man he later described as ‘the most bitter man I ever knew.’ He had eight half-siblings, who as a child he helped to raise. Aged 24, Baldwin bought a one-way ticket to Paris, arriving with $40 in his pocket, in order to escape racism and homophobia, a move that he described as having saved his life. His semi-autobiographical first novel, Go Tell it on the Mountain, was published in 1953 to excellent reviews. His second novel, Giovanni’s Room – a gay love story set in Paris, with no black characters – was far more controversial and his American publisher refused to touch it (his English publisher felt differently). His third novel, Another Country, published in 1962, combined the themes of race and sexuality and was an immediate bestseller. In parallel, he was writing essays and his 1963 collection The Fire Next Time was also a bestseller. The Civil Rights Movement brought him back to the US for much of the 60s. Later, he settled in the South of France, where he died in 1987 from stomach cancer.

The short stories in the 1965 collection Going to Meet the Man were written over a period of more than fifteen years and cover familiar Baldwin themes. Alongside race, sex and sexuality, and romantic love, Baldwin explores coming of age, religion, love within families, the role of the artist and the power of black music.

The collection starts with two stories whose cast of characters is familiar to anyone who has read Go Tell it on the Mountain. Whereas the central incident in ‘The Rockpile’ – John’s younger brother Roy is badly injured – is recognisable as something that also happens in the novel, the second story ‘The Outing’ is a more developed offshoot. With its vibrant depiction of the Harlem church community Baldwin grew up in and its final moment of painful self-discovery, this is my personal favourite.

The boat trip up the Hudson River starts with a sense of high expectation. The church ‘saints’ (‘very conscious… of their sainthood’) are hoping to make converts; Johnnie’s father is hoping to preach; David (Johnnie’s friend) is hoping to woo Sylvia; and Johnnie is hoping to spend the day with David. None of these hopes are to be fulfilled and the story is a study of small scale disappointment. The apparent lack of drama contrasts with the often heightened pitch of the language as Baldwin skilfully captures both religious fervour and teenage intensity.

The main focus is the three adolescent boys: Johnnie, David and Roy. Their parents may be hoping ‘to bring their souls to safety’. But the boys – whose bodies are ‘preparing them, mysteriously and with ferocious speed, for manhood’ – have different ideas. And though the plot apparently centres on their attempts to win Sylvia’s affection, Johnnie’s real interest is slowly revealed. A third of the way in, Johnnie and David head to the topmost deck. Alone, they put their arms round one another:

‘Who do you love?’ he [David] whispered. ‘Who’s your boy?’

‘You,’ he [Johnnie] muttered fiercely, ‘I love you.’

The depth of feeling is cleverly heightened by the contrast with the subsequent line:

‘Roy!’ Elizabeth giggled. ‘Roy Grimes. If you ever say a thing like that again.’

The middle of the story is taken up by the church service. This is a religion of saints and sinners, in which the Holy Ghost jumps on people. The service has tambourines, singing, clapping and feet stomping so hard the floor trembles. There’s an impromptu back and forth between preacher and congregation. People shout, scream and sob. Arms wave and people dance in the aisles. With the contrasting images of how ‘in that moment, each of them might have mounted with wings like eagles’ set against ‘the doom of hours and days and weeks’ we sense the way religion provides a thrilling escape from the characters’ drab everyday lives.

Amidst the high emotion, Johnnie remains unmoved: ‘Yet, in the copper sunlight Johnnie felt suddenly, not the presence of the Lord, but of David …’

David finally manages to talk to Sylvia, who proves the ultimate wet blanket, interested only in seeing him in church, while Johnnie is left miserable and alone. And though the final paragraph shows the boys apparently reconciled, with David once again putting his arms around Johnnie, everything has changed:

But now where there had been peace there was only panic and where there had been safety, danger, like a flower, opened.

The ending is exceptionally beautiful, and heartrending. But not necessarily hopeless. Understanding what he faces as someone black and gay feels a necessary part of Johnnie’s growing up.

‘The Man Child’ is the only story with no black characters. This tale of repressed sexuality and envy leads to a shocking conclusion. Alongside the more dramatic elements, there is much to enjoy in the quiet observations such as when, following his mother’s miscarriage, eight-year-old Eric describes how ‘His father laughed less, something in his mother’s face seemed to have gone to sleep forever.’

Originally published in 1948, ‘Previous Condition’ is the earliest example of Baldwin’s published fiction and draws on the writer’s frustrations and anger at experiencing everyday racism in New York. A black actor is temporarily staying in a truly hideous room rented for him by a Jewish friend, who advises Peter to ‘Sort of stay undercover.’ When Peter is unlawfully evicted, it’s just one more example of a broader pattern of injustice. Lines such as ‘I’d learned never to be belligerent with policemen, for instance. No matter who was right, I was certain to be wrong’ remain all too relevant today.

‘Sonny’s Blues’ is the best known of Baldwin’s stories and has been frequently anthologised. It centres on two brothers and though the upright narrator (an algebra teacher) is likable enough, Baldwin’s sympathies clearly lie more with the younger Sonny who dreams: ‘I’m going to be a musician … I want to play jazz.’

His older brother falls back unimaginatively on cautious practicality, ‘Can you make a living at it?’ he asks.

Sonny’s response: ‘I think people ought to do what they want to do, what else are they alive for?’ sounds very much like that boy from Harlem who was determined – against all odds – to become a writer.

As important as the characters are the sense of time, place and alienation. Entering Harlem, the narrator observes the way the streets ‘seemed, with a rush, to darken with dark people.’ Dark skin equals dark lives. Childhood memories are full of ‘darkness’, both literal and metaphorical. And these images are coupled with the sense that nothing ever changes.

We follow the brothers through various estrangements and personal difficulties. The narrator’s two-year-old daughter dies; Sonny is jailed for peddling heroin. But the story has a transcendent ending in which the narrator goes to hear Sonny play and it’s here in the darkness of the jazz club that he achieves an understanding of his brother and he, and the reader, are finally offered light.

This final section is gorgeously lyrical and endlessly quotable. To choose just a few lines:

Creole began to tell us what the blues were all about. They were not about anything very new … For, while the tale of how we suffer, and how we are delighted, and how we may triumph is never new, it always must be heard. There isn’t any other tale to tell, it’s the only light we’ve got in all this darkness.

Although Baldwin is talking about jazz, there are clear parallels here with Baldwin’s own calling as a writer.

In ‘This Morning, This Evening, So Soon’ we enter the dilemma of a successful black actor/singer who, after twelve years living in France, is returning to the US to take up a lucrative film opportunity. He reflects: ‘It [Paris] saved my life by allowing me to find out who I am,’ closely echoing Baldwin’s own feelings. The narrator is married to a white woman, something that would have proved impossible back home where Harriet would have been ‘degraded by my presence.’ And they have a child who has never experienced racism. The narrator knows he will need to relearn ‘all the tricks on which my life had once depended’ and anguishes over how he can prepare his son:

for all the tireless ingenuity which goes into the spite and fear of small, unutterably miserable people, whose greatest terror is the singular identity, whose joy, whose safety, is entirely dependent on the humiliation and anguish of others?

The only story with a female narrator, ‘Come Out the Wilderness,’ depicts a love affair between a black woman, Ruth, and an unreliable white artist. The story portrays the pain of being in love with someone who is not in love with you and contrasts Ruth’s feelings for her lover with her indifference towards the staid black suitor who others assume is a desirable match. Alongside the personal story is a caustic description of her workplace, which is

… sufficiently progressive to hire Negros. This meant that she worked in an atmosphere so positively electric with interracial good will that no one ever dreamed of telling the truth about anything.

The final story, ‘Going to Meet the Man,’ was written in 1965 at the height of Baldwin’s involvement in the Civil Rights Movement. Narrated by a white racist sheriff, Jesse, it’s an outlier in terms of Baldwin’s fiction. And as readers, it’s relatively rare to read from a viewpoint that is so monstrously wrong.

The story starts with Jesse in bed with his wife and unable to perform sexually. His mind wanders back, first to the events from earlier that day – beating up a Civil Rights protester – and then back much further.

The childhood flashback starts with a slow, sinister build up. There’s a sickening sense of levity as white people drive round letting each other know that the black man on the run has been found. Lines such as: ‘He [Jesse] knew she [his mother] wanted … to put on a better dress’ are hugely chilling in the context of what follows.

On the journey, eight-year-old Jesse remarks:

he had not seen a black face for more than two days … there were no black faces on the road … no black people anywhere. From the houses … no smoke curled, no life stirred … There was no one at the windows, no one in the yard, no one sitting on the porches …

With this long list of what is absent, Baldwin seems to ask us to pause and consider the story which isn’t being told. What is this like for the black community imprisoned behind those windows and powerless to prevent the coming atrocity?

The scene of a lynching, in which we witness the torture and murder of a human being, feels almost too vivid. The obvious horror is compounded by the frenzy of the white mob with their ‘delight rolling backward’ and by the fact the events are viewed through the eyes of a child. Jesse’s confused emotions range from terror, to wonderment, to a twisted kind of joy; he sees the mutilated body as both ‘beautiful and terrible.’ The protracted details of the man being castrated are nearly unbearable to read.

Back in the present, the story concludes with an ugly and disturbing scene in which these terrible memories feed into Jesse fantasising that he and/or his wife are black, allowing him to regain his sexual potency. The sex is utterly joyless and the final images are of a deeply damaged man. If we’re to feel anything for Jesse, it helps perhaps to reflect on this quote from one of Baldwin’s essays: ‘I imagine one of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, they will be forced to deal with pain.’

In 2016, when President Obama opened the new National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington D.C., he started his speech with the words ‘James Baldwin once wrote …’ and proceeded to quote a line from ‘Sonny’s Blues’ not once, but twice. I will also repeat it: ‘For, while the tale of how we suffer, and how we are delighted, and how we may triumph is never new, it always must be heard.’

The tales in this collection remain as urgent and powerful today as when they were first published. They deserve to be heard.

***

Sarah Evans has had many short stories published in anthologies, literary journals and online. Her stories have been shortlisted by the Commonwealth Short Story Prize and the Alpine Fellowship, and awarded prizes by, amongst others: Words and Women, Stratford Literary Festival and the Bridport Prize. Her work appears in several Unthology volumes, Shooter Magazine and TSS Publishing. She is also an avid reader of stories, both short and long. She tweets at @Sarah_mm_Evans