Review by Becky Tipper

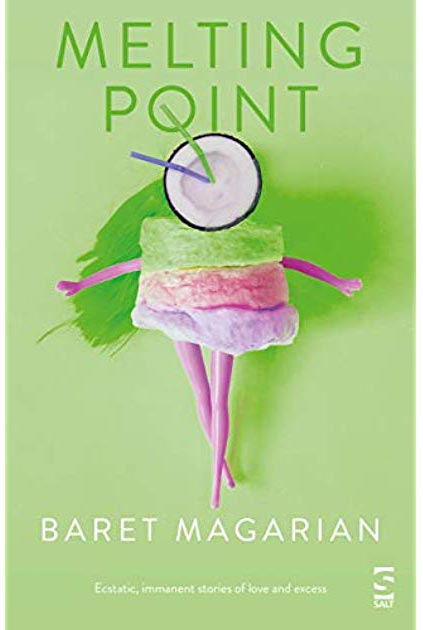

Publisher: Salt

Publisher: Salt

214 pages

Price: £9.99

ISBN: 978 1 78463 197 0

Baret Magarian has the best sort of author’s bio, with a motley, intriguing catalogue of past jobs – he has been a lecturer, translator, musician, journalist, stage manager, book representative, and nude model. And, aptly, the fourteen stories in his first collection are a pleasingly eclectic mix. In Melting Point we meet deep-sea divers in Greece; a humble greengrocer in Florence; fishermen in a fantastical Cornwall; tourists backpacking in Sri Lanka; and a fast-talking American courier spending the night in a noir motel. Some stories are magical, others stylish fables, others sensitive explorations of characters coming to terms with the contradictions of existence.

Despite their variety, these stories have some common elements; they are playful and often philosophical, featuring characters who muse aloud about the meaning of life and the nature of reality. And Magarian’s well-stocked vocabulary is evident throughout, so that in any story you’re likely to encounter such magnificent words as ‘tenebrosity’ and ‘etiolated’.

These stories are also strange. No matter the subject or setting, the stirrings of the subconscious usually lurk just beneath the surface. For example, in ‘Crime and Bread’ a woman becomes infatuated with a Toulouse Lautrec poster that she sees in a shop window. But her desire takes a peculiar turn: she becomes seized by the idea that if she is to have it, she must steal it: ‘She could have afforded to buy it, that wasn’t the issue, she just felt that stealing it would represent some kind of victory over life, would amount to an act of necessary defiance.’

And while inexplicable urges drive the action, many stories also feature a mysterious moment of epiphany where the protagonist touches a cosmic truth. For one character, this experience is ‘as though her body were a conductor of energy, and she had been plugged into the universe’s nameless current’. For another, it’s a sexual encounter on a dawn beach which ‘was like some fabular perfection, as though the elements and nature were conspiring to make their dreams come true in a final and rare departure from the notion of nature’s cosmic disinterest in man’s petty little affairs.’ I loved this attention to the ineffable experiences that transform people’s lives.

Another of my particular pleasures in this collection was Magarian’s use of a tale-within-a-tale, such as the one which features prominently in ‘Island’ (which is an enjoyable and complex story reminiscent of John Fowles’s novel The Magus). In this story, a young Englishman on a Greek island falls under the spell of a mysterious woman (and there are many such women and men in these pages – spinners of fabulous tales, charismatic and possibly unhinged geniuses). We are drawn in, along with the narrator, as the woman relates an incredible story of how she experienced a time-slip in a London Underground station and found herself suddenly in the year 2043. This sub-story is itself as amusing and engaging as the one in which it is embedded.

There are wonderful little tales nested within ‘Fever’ too. Here, a courier must deliver an incendiary manuscript by a renowned and eccentric novelist. In passing, Magarian regales us with an array of stories from the novelist’s past catalogue. They include such gems as:

The Millions (2004) a 900-page satire about an agency in New York that specializes in faking alternate lives for people whose own lives are boring and uneventful. The agency produces documents, diplomas, certificates, letters, emails, creates an illustrious, exotic past for those who come knocking at its door. Eventually the real and the fake become indivisible as people struggle to concoct even more lies to support the original lies. The fake biographies sabotage the actual until reality itself becomes one vast and bloated invention.

There’s something delicious about these nested stories, intricate and fascinating as Russian dolls. And (perhaps this is the intention) they also throw the very act of story-telling into question: How do some stories have such a powerful hold on us? And whose stories should we believe?

The device of a tale-within-a-tale also appears with striking effect in ‘The Rich and the Slaughtered’ where the action pivots on a tale which is actually heard third-hand: a silent character listens to a man recount a story in which another man tells a story which, apparently, ‘contains the secret of the world’. But although this makes for an intriguing structure, the central concern in this story is actually the nature of suffering and inequality. ‘The Rich and the Slaughtered’ confronts the uncomfortable truth that some people inhabit a world of extraordinary privilege and wealth, with servants catering to their every whim, while at the same time, small children live in warzones. And how, after all, do we live with the reality that some are born to sweet delight and others to endless night?

Magarian returns to this conundrum in ‘The Opiate Eyes of the Buddha’. In this story, two Western tourists in Sri Lanka visit a luxurious hotel (complete with infinity pool and obliging staff), but their travels unfold against a backdrop of post-tsunami devastation and horrific brutality. (And readers may want to be prepared for the particularly graphic violence depicted in this story.) I did wonder, on first reading, whether this story (and ‘The Rich and the Slaughtered’) veered close to becoming didactic. But in the end, I was transfixed and appalled by the events in the two stories, and deeply moved by the characters’ (and author’s) desire to find solace or meaning in a world that is often incomprehensible and unjust.

Although there are some heavyweight stories here, some of my favourites had a simpler, more narrow focus. The aforementioned ‘Crime and Bread’ (whose protagonist feels mysteriously compelled to steal a poster) is elegant and strange; almost a fable. And ‘The Balls’ is a wonderful Boccaccian yarn. The hero of ‘The Balls’ is Salvatore, a gnarly and unsophisticated Italian greengrocer who has a superstitious relationship with his testicles,

…he touched his balls, as Florentines did. To ward off evil, whenever evil seemed about to come his way, which was most of the time, or whenever an ambulance rattled past, impaling all the grace of the old city.

But when Salvatore’s first son is born and appears to be a prodigious genius, Salvatore is at once mystified and proud that his ordinary testicles have produced such remarkable offspring. Both stories are delightfully quirky and satisfying.

Admittedly, there were stories in Melting Point that didn’t quite transport me. In ‘Erasing the Waves’ for instance, a porn-addled slacker bumps into an old friend who has become a successful filmmaker, and the filmmaker shares a dramatic anecdote with his old friend. However, the revelatory effect of this confession passed me by and the story felt a little forced. And in a couple of stories, I felt that intriguing concepts fizzled out and weren’t carried as far as I might have liked (such as ‘The Visitation’ where bizarre, unidentifiable creatures start to wash up on a beach). Nevertheless, there’s a raw and enigmatic energy to Melting Point. And if, occasionally, these stories didn’t quite resonate with me, there were many moments when their haunting images and impulses did get under my skin – Magarian certainly has an enviable knack for plumbing the murkiest depths of the psyche and for expressing the ineffable.

Overall, this is an ambitious collection which is at once clever and heartfelt. Melting Point’s stories take the reader on a journey through the extremities of human experience, taking in suffering, hedonism, genius, ignorance, inexplicable horror, and nirvanic insight. And it’s a wild and exhilarating ride.

***

Becky Tipper is passionate about reading and writing short fiction. Her stories have appeared online and in print, in publications including Prole magazine, The Lampeter Review and For Books’ Sake. She has won the Bridport Prize and has been runner-up in the Society of Authors’ Tom-Gallon short story award. Becky was born in the West Midlands but currently lives in Maine.