Review by Rupert Dastur

Ode to LSSF:

A wonderful weekend at Waterstones

To hear some awesome author tones.

The London Short Story Fest –

We’ve heard it is a whizz,

No matter the time it is –

The London Short Story Fest

It really is the best,

It is, it is, it is…

It is the London Short Story Fest!

I’ve been told I should stick to prose. Personally, I think this would be a tragedy for the wider world, but what do I know?

I’m sitting in a chair (as one generally does when sitting), waiting to hear about Flight 1000, an initiative by Spread the Word. The gregarious Paul Sherreard introduces the event and the scheme: ‘The aim is to help London writers and those underrepresented in the publishing industry.’

The arrangement offers successful candidates (‘associates’) one thousand paid hours, working as an intern for various companies in fields such as publishing, editing, and literary agencies. These hours also include time for writing. It’s a fantastic initiative that has the opportunity to really launch a career. Whether you’re unsure of what you want to do or where you want to go, it’s well worth looking more into this generous organisation. More details can be found here.

The three associates – Len Lukowski, Jennifer Obidike, and Sanya Semakula – are clearly appreciative of the all that has been offered and though two of them are keen on launching a career in writing, the experience and insight they’ve been given into the publishing industry will no doubt help them in the future. With this in mind, I ask whether they’ve noticed any tensions among publishers, agents and writers over the divide and confusion over the digital vs traditional publishing. Does it feel like there is a heart deal of turbulence and uncertainty?

The three speakers provide similar responses, with Lukowski offering the most substantial reply. The industry, we’re told, seems to be straddling the divide reasonably well, and that while there are shifts going on between the two pathways, it’s less a condition of uncertainty than the general adaptation to technology that all industries face.

Following these questions, we were asked to get into pairs and draw a map of the publishing industry, including all the various avenues that involved creative writing of one kind or another. I was sitting next to Safiha Akram, who wished to become a published poetry. We scribbled down our map that encompassed agents, publishers, societies, charities, online publishing, self-publishing, creative courses, writers’ retreats, literary events, speakers, festivals, editors, proof-reader, writers, and more. The point was to demonstrate that there were plenty of avenues one could go down in order to remain part of this churning, if hard-to-navigate, writing world.

After this event, I was more than geared up for the Masterclass with Ben Okri. It was a relatively pricey event at £35, but for a writer who only gives one class every fifteen years or so, it seemed like an opportunity I couldn’t miss.

Roughly thirty of us were seated in a semi-circle, creating an inclusive atmosphere that seems typically Okri-esque. In the great man strides, wearing a royal purple shirt and (let it not be forgotten) a beret.

First, we are to give the briefest of introductions. All of us. Okri zips around the room. Name and occupation are given (the most common of which: ‘X, writer’) and if anyone went beyond this, Okri would pause and look at them, ‘We need to work on your prose,’ he would say. This is a class for the short story, he reminds us. Short, short, short.

Introductions done, we are presented with a question: ‘What are we doing?’

The answers are various and many: Thinking, writing, listening, being, imagining, seeing, worrying, hoping… And one wit, ‘Guessing.’

Okri writes a word on the whiteboard Open. ‘Finish that word for me,’ he says. We do. ‘Opening,’ he says, ‘that’s what we’re doing here. We’re opening.’

There is not much time to think about this, before another question is thrown our way: ‘What is more important… what comes higher than inspiration?’

Again, several answers are given: dedication, passion, hard work, imagination, routine.

Okri nods along as words are projected out into the open.

‘Inspiration,’ he begins, ‘is maybe the most important thing about creativity. I have read so much about it, I have spent so much time thinking about it that I am at a fascinating loss at where to begin. I think that it is when you are thinking at your full capacity – at your very best, that there comes a lightness of touch, and suddenly you have wings and you soar. You soar high up for the briefest of times and then you come down. You soar, not because of any special talent, but by something other; it is genuinely astonishing. Poets worship inspiration for this reason; it is unknown, mysterious, it lets you soar. Perhaps it is this – the quality of inspiration – that separates poets and novelists.

‘I was watching a film last night – We Are Many – which I recommend and encourage you to go out and watch. And the title is from Shelley’s poem ‘The March of Anarchy.’ And the film sent me off in search of this poem and I read it, and I was so tired at this time, but then I came to the last stanza and there was this line: ‘Rise like lions from slumber’. There is was… that was Shelley, rising, soaring. You know, the rest of the poem was walking along, but then he had wings. ‘Rise like lions from slumber’ I read, and the hairs on my arms stood up.’

Okri pauses and then points to a picture on the left and a picture on the right. The one opposite me is a copy of ‘The Son of Man’ by Magritte. The other, behind me, is a photograph of a bronze (?) head, from some ancient time. ‘You have two minutes,’ said our instructor, ‘I want you to write two lines.’

Faces turn towards empty paper, and pens are poised in anticipation, waiting for… well, inspiration. I look at the man in the suit with the apple obscuring his face. Where are my wings? Where is my inspiration? The clock ticks. I scribble some words. Too dull. I cross them out. I write again. I feel I’m being too literal, but here we have it:

‘The tie snaked around his neck. Adam was slowly choked with greed.’

I was trying to be clever with images and symbols and what-not. Now it seems rather dull. I look at the other faces around the room. There is a slight nervousness in the room. We’re sitting before one of the greatest writers of our time, and here we are with our humble offerings. He points to someone. ‘Pease read,’ he says. It is not a request.

We hear several lines form a dozen writers in the room.

‘And how did you feel?’ he asks.

Excited, say some. Scared, worried, stressed, exhilarated, pressured, liberated.

The range of responses is quite a surprise and yet this is something I’ve come across time and time again. Writing is an individual process and there is no ‘right’ way of going about it. Some people need the pressure of deadlines, others loathe it. Some write by hand, some by computer, some dive in, others plan. The only consistent factor I’ve seen and read about is this: hard work. Getting the words down on the page, and doing whatever it is you need to do to achieve this.

Okri is back to his favourite topic. ‘Inspiration for me,’ he says, ‘is about vibrations. Everything is moving. It’s about seeing that and suddenly not being yourself, but being yourself more than ever.’

Portrait, by Ben Oki. He demonstrates the importance of seeing and recollection. The artwork is signed later.

Portrait, by Ben Oki. He demonstrates the importance of seeing and recollection. The artwork is signed later.

‘I feel like being naughty,’ he says suddenly, smiling a little. ‘Quickly everyone on this side of the room go over to that side and vice versa. Quickly now,’ he says, speeding us towards our new seats.

The two sides of the room swap over and I’m now facing the photograph of the bronze busk.

‘You have thirty seconds. Write as much as you want to about the image opposite. Don’t think!’ commands Okri.

I look at the photograph and then at my paper and begin to write. I have no idea what I’m doing. This was my attempt:

“What did it say?”

“It said that Death was coming.”

“Death?”

“I think we should leave, Thomas.”

“It’s just a statue, Benj.”

“But it said that Death was coming.”

A little melodramatic. But who doesn’t love a bit of drama, right?

I found the pressure to write provided freedom – there was no desire to be clever, to edit, there was just time to write providing a connection, a stream of imaginative movement straight from the mind to paper.

‘How did you feel?’ asks Okri. Similar answers follow as with the previous question: liberated, too much pressure, uninspired, inspired.

‘There is a point in writing,’ says Okri, ‘when we have to leave thinking behind. You see we are the ones preventing ourselves from being inspired… We should learn to let a higher mind take over. It’s about our receptivity to the world, while trying to escape the tyranny of thinking.’

A few people had struggled to write anything during the last exercise. There was too little time, they said. The pictures were not inspiring. Okri addressed this head on: ‘Inspiration starts with us. We must be awake to all that is around us.’

He continues, ‘We should be able to see or hear anything and be able to reproduce it in some way. Being a writer is being a perpetual witness to reality. Inspiration can only call forth that which we have already put in… It is not called inspiration if you do nothing with it.

‘Tchaikovsky called inspiration ‘the unwanted guest that comes when you’re busy.’ But inspiration is like dreaming, like dreams; it is notoriously fragile.

‘Sometimes I have what I call radical structural inspiration. I could be two hundred pages in and then it will come to me that I should be approaching the story from the angle of a tortoise, for example. And when that happens you look at your two hundred pages and you want to lock the inspiration away. But it is a wonderful thing, this inspiration, and you should grit your teeth, be humble, and start again.’

He pauses and looks around. He has another question for us: ‘What are you going to do with the discrepancy between flying and walking?’ he asks, referring to those moments of inspiration compared with the daily struggle of the craft.

We provide several answer and he listens to all of them and deliberates. At last he brings a hand to his beard, ‘I am not going to tell you what I think on this, but it’s an important question, and one you should consider deeply.’

BUT, MR OKRI SIR, I HAVE PAID THIRY-FIVE POUNDS AND WOULD LIKE TO KNOW THE SECRETS OF WRITNG AND ALL THE MYSTERIES OF THE UNVERSE, PLEASE.

But no, that is not his way.

‘Steady walking is the part that you must absolutely depend on,’ he says, referring to the daily slog of word-slinging. ‘But we judge too much… Do not judge before you write, or during your writing… All of that wonderful creation you’ve got, just get it down.

‘Watch yourself. Watch for the patterns in your creativity. Watch for when writing seems to work for you, when the magic seems to happen. Study the patterns of your creativity.

‘Writers write; that’s what we do. No magic can happen if you don’t write. Though there is a corollary to that – really good writers re-write. No matter what inspiration you have, you still have to shape it. The choice of where you begin your story is half the battle.

‘And this: always be open. Be open to things that are difficult, be open to new experiences, new writing. Be open, be receptive – and if you do this for long enough, that unwanted guest… maybe it will come knocking.’

Although we did not do a huge amount of writing, one thing that Okri did provide was plenty of important matter to think about. This might seem rather ironic, given his previous comments about thinking… Still, it was an enlightening masterclass, and an excellent catch for the LSSF.

The next event was Food and Writing, showcasing Elaine Chew, Krys Lee, Charles Lambert, and Ben Okri. There was also wine and homemade cheese sticks.

The first question concerned the writers’ favourite dishes. Chew gave a nod to noodles, Okri had a penchant for pepper soup, Lee liked ethnic foods – particularly Korean: ‘Food,’ she says, ‘provides a primitive pleasure, as well as one of nostalgia and memory.’

Lambert had a love for Italian food, which he connected with conviviality. ‘I now live in Italy and I always associate it with long tables, music, dogs under the table… For me English food is more associated with embarrassment: the moments when I was young and learning to behave.’

‘There is a relationship between short stories and food,’ says Okri. ‘A time when you are by the fireside and your mother is cooking, and while she is preparing the food she is chatting to you, telling you stories.’

The three writers give readings of their work. Lee’s short story was a slightly political, humorous tale about a boy from South Korea trying to avoid mandatory military service. The short story (‘Fat’) begins with the lively and direct line, ‘There was only one word to describe me and that was fat.’ The narrator eats ad eats, much to the shame of his father. It’s an amusing short story, but the style belies the heavy subject-matter. Lee later tells us that many try to avoid military service, going so far as to amputate their fingers.

Okri gives a rhythmic performance of one of his ‘Stokus – a cross between a Haiku and a short story – he tells us. The language of his story (The Mysterious Anxiety of Them and Us’ is immensely sparse, and the tale is fabulist in tone and content, ‘They did nothing. They didn’t even come over, take a plate, and serve themselves. No one told them, to just stand there watching us eat. They did it to themselves.’

Lambert’s short story was of the more traditional kind and is partially autobiographical. It is set in the midlands and is about a young boy and his relationship with his mother (this theme seems strikingly prevalent in short stories). The tension is wonderfully balanced, gradually rising as the story continues. There is a sense of huge dissatisfaction and entrapment that is given dark release through the simple smashing of eggs. Lambert is another find.

The glass of wine did not go amiss.

The glass of wine did not go amiss.

We move onto a little more discussion and among the general chatter a few choice quotes surface…

Okri: ‘Writing for me is much like cooking… there is a kind of alchemy to it.’

Lambert: ‘Short stories… they’re like cooking calamari. Either done very, very quickly and to perfection, or very slowly, given a long time to cook and get right.’

Lee in her delightful enthusiasm: ‘I’m always eating. My laptop is covered in crumbs, my notebook with coffee stains. I’m satisfying the pleasures of the mind and the body. Besides, chewing always wakes you up!’

Okri: ‘The act of writing is very difficult… we eat as a way of feeding ourselves with the necessary energy. There’s also something ritualistic in the act of cooking, as in the act of writing. We are creatures of habit, of rituals. I know someone who only ever writes in their pyjamas and they don’t wash them until they have finished the project.’

Lambert: ‘Writing is the only time when I won’t be eating. Writing is a solitary business, and I always associate eating as a convivial activity.’

The final event of the day is called ‘Modern Voices’ and is chaired by Festival Director, Paul McVeigh. Featured writers include May-Lan Tan, Laura van den Berg, and Jon McGregor.

We begin with three accomplished readings, filled with ample humour, depth, and poise.

The questions then begin. ‘What is it about the short story form’ asks McVeigh, ‘that draws you to it?’

Tan opens up the response, ‘You can afford to be more intense in the short story than you can in the novel. If you’re experimenting with a particular voice or constraint, you can sustain that in a short story, while it would seem gimmicky in a novel.’

‘Because of the length?’

‘Yes, exactly.’

‘A lot of short stories seem to be written in the first person…’

‘Yes,’ responds Tan again, ‘I favour the first person in short stories. I think it’s not always right for the novel, unless it’s in the voice of a teenager, or a character that brings the whole force of their present experience to bear on the narrative.’

‘I love the compression,’ adds van den Berg, ‘and you can experiment with the short story. And for me as a reader… I’ve had experiences that are absolutely as powerful and extraordinary with the short story as with the novel. The ability to distil thought and feeling and landscape – I marvel at all this in short stories.’

‘And does the length influence this… when there are only a few pages left and the tension is kept up?’

Van den Berg: ‘Absolutely. The other thing that you have with short stories – it’s a bit easier to get on board because of the length. You start in the middle of it; you jump off one cliff and then end up at the top of another. It’s heart stopping. When I’m reading a short story, I want to see what sort of cliff we’ll be getting to and what the new view will look like.’

‘What I like about short stories is that they’re going to be read in one go – unless you’re dealing with a particularly lazy reader – and so you know you have complete control of the story and how it’s going to be read. You trust that they’ll experience all of the short story… a short story is a bit like going to the cinema – it’s a total, exciting experience,’ offers McGregor.

‘Some people see the short story as a joke. Like it’s something to start out with, but not really what a agent would look for. Do you feel like you’re constantly under pressure to write a novel?’ asks McVeigh.

‘No, not personally,’ says Tan, ‘That’s probably because my novels weren’t getting published, while my short stories were. The thing is to be as good as you can and not worry about genre or that kind of thing.’

‘I haven’t really, either,’ says van den Berg. ‘I attempted a novel because that happened to be the architecture of the piece. But the short story was the first form I encountered and fell in love with – Alice Munro and short story writers like that. I signed with an agent after sending in a collection of short stories, but I never felt the pressure to write a novel. We don’t have that kind of control over what we write!’

McGregor offered a different opinion, ‘Yeah, they keep banging on about writing a novel. Short stories are harder to sell than novels. But I’m not bothered too much and have just carried on. You just write what you write. As soon as you start to write something you think someone else wants, you’re going to land in trouble.’

‘A simple question, but could you name us some writers that have inspired you?’

Van den Berg: ‘Alice Munro, Amy Hempel, Deborah Eisenberg, Edward P. Jones, Malcolm Cowley are all great short story writers, among other’

Tan: ‘Mary Gaitskill – she takes a moment, turns it into layers of Saran Wrap and picks them apart, and trusts us not to be impatient with that. Simon Van Booy – his writing is very poetic and he has a voice completely his own. I also love Nam Le.’

McGregor: ‘Alice Munro, George Saunders, most of the population of Ireland. I also like shiort story writers that challenge the short story form – Lydia Davis, Donald Barthelme, Ben Marcus, – I think that they do something very exciting with the short form.’

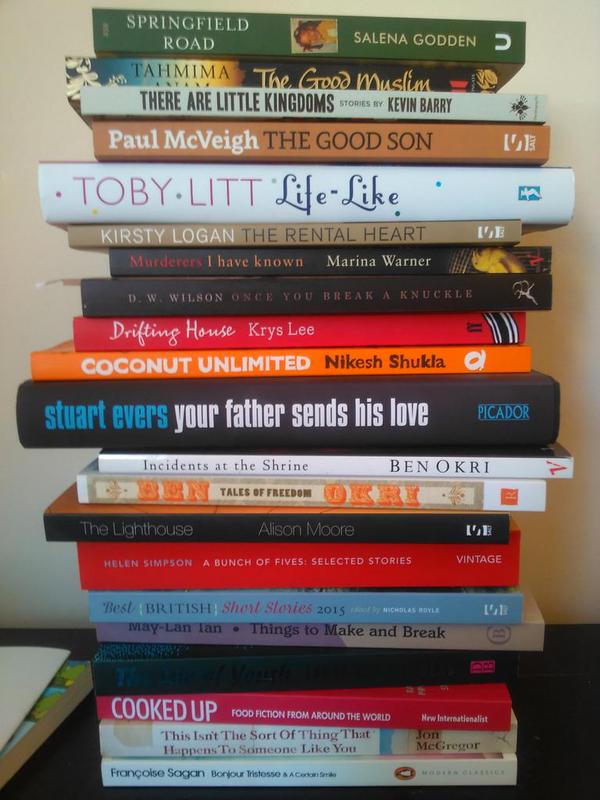

Breaking the bank with books

Breaking the bank with books

The final question is one of the million dollar one. ‘How short is a short story?’

McGregor has a simple answer: ‘If I can read it in one go, then it’s a short story.’

Van den Berg says that ‘When I write, the short story takes however much space it takes; then I go over it and try to make it as tight as possible.’

Tan meanwhile suggests that ‘a short story can be anywhere between five and fifty pages. But I like to have some range because I myself tend to read collections in one sitting and so I enjoy some variety.’

This concludes the final event and the day. Day three and as stimulating as the first. What revelations I wonder, will tomorrow bring?