Review by Jo Mazelis

The more I read these stories, and read up about their author, Lucia Berlin, the more I felt that I had arrived at the party rather late and was the only one there who wasn’t already aware of the blue-eyed host’s legendary charm and infamy. This edition of her selected stories comes with a foreword by Lydia Davis, an introduction by Stephen Emerson and at the end of the book ‘A Note on Lucia Berlin’ which is a potted biography. The stories and equally the story about Berlin’s life made me want to know more about her. I found a recollection of Berlin in The Paris Review by Elizabeth Geoghegan. Geoghegan, reflecting on the issue of the autobiographical content of Berlin’s stories, said ‘She could have chosen memoir, but I think she knew she was chosen to a higher art.’ This simple statement gave me a little rush of pleasure as it seemed to answer all the questions I had been turning over in my mind while I read the stories in ‘A Manual For Cleaning Women’ and had debated for some time before.

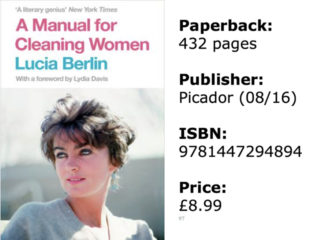

In some ways the cover of the paperback edition of this book repeats this same trick because the photograph used shows the author herself in 1963, yet the image is more than that, it is reminiscent of the sort of retro images used on the covers of The Smith’s albums in the 1980s. Lucia (pronounced Lu-see-a) Berlin wears a dove grey cashmere sweater, earrings with two blue dangling stars. Her skin tone is pink, her lipstick pinker, her eyebrows dark and thick and shapely, eyes exaggerated and defined by smudged kohl, mascara and eye shadow. Her hair is short, ruffled and nut brown. Eyes blue. Neck swan-like. She bears a passing resemblance to Liz Taylor but sprinkled with a smidgeon of Anne Sexton. It seems appropriate somehow that a writer who has been sliding under the radar for forty or more years should at last, quite literally, show her face.

Lucia Berlin is superb at exposing the lives of her predominantly female characters yet everything is achieved with a lightness of touch, a seeming effortlessness. In the first story of the collection ‘Angel’s Laundromat’ a woman notices an old Indian man looking at her hands; so she too looks and sees ‘Horrid age spots, two scars. Un-Indian, nervous, lonely hands. I could see children and men and gardens in my hands.’ There is so much psychological truth packed into just these three sentences; discomforting self-awareness, recognition of the effects of time and aging, an insight about race – the implied disadvantage of the white race’s hands (more prone to wrinkles, age spots? Less elegant and eloquent and useful than a Native American’s?) and lastly, the sense of being used up with work; work done for children and men and gardens that she sees ‘in her hands.’ Like many of her stories it is about lives that brush one another in passing, she and the Indian eventually joke and chat together, then one day he’s gone and ‘I can’t remember when it was that I realized I never did see that old Indian again.’ But ‘Angel’s Laundromat’ is also disjunctive, as disorganised and random as memories, for the narrator’s account of one laundromat in New Mexico is represented alongside that of another in New York. These are places of washing and waiting, muggy places, tinny places that serve an underclass of people, students and bedsit dwellers, the poor, the old, the indigent, and she, ‘Lu-chee-a’ as the Indian calls her, is among them. It is in this sense that the story is both aimless and easy; it does not strain to be more than itself and in this way it evokes the looseness of a certain sort of life, a life lived bumping around on the bottom no matter where you began. It doesn’t matter what you are, either a woman who once mixed with Prince Aly Khan or a man who has been dispossessed of his status as an Apache chief, now you are there and that’s all there is.

The story that gives the book its title ‘A Manual for Cleaning Women’ immediately highlights Berlin’s subtle cleverness and offers an interrogation of the service and sexual roles women perform. A dirty woman is a sexual woman, a cleaning woman is a hired domestic. So does the title refer to a guide for making dirty women clean, purifying them? Or is it a book of instructions for those whose work it is to clean other people’s workplaces and homes? As it turns out it is full of wry instructions for cleaning women (though these are not the tips on washing windows one might expect), but it is also a forest of signs – the literary equivalent of a hyper realist painting of a shop window by Richard Estes – with bus destinations, slogans and notices printed in caps; BLIND, SUICIDE PREVENTION, MAGIC WAND BEAUTY PARLOUR. It seems like the shabby territory of a Coen Brothers film, Fargo perhaps – exposing everything that is overwhelming and broken about late capitalism, the way it dwarfs the little people; the cleaners and the drunks, the street people. The narrator is a cleaning woman, she has four sons and her husband is dead. She is ‘educated’ but this is the only work she can get. It is a story that is packed with truth, filled with small facts that illuminate the lives of those caught on the lowest margins. One man she cleans house for asks why she ‘chose this particular line or work.’ An idiotic question because at that level of need for employment no choice is involved. She answers disingenuously, ‘I figure it’s either guilt or anger’ perhaps because he is a psychiatrist – not that he pays much attention to her answer.

The story is structured around her various cleaning jobs in different people’s homes and the buses she catches to get to them. These passages are interspersed with bracketed instructions as per the pretence that the story is a manual:

(Cleaning women: You will get a lot of liberated women. First stage is a CR group; second stage is a cleaning woman; third divorce.)

The facts of the narrator’s situation are peppered in modest doses along the way. At the end on ‘a cold, clear January day’ for no particular reason aside from the ongoing weariness, the sense of being in a life from which there is no escape, the narrator says, ‘I finally weep.’

One of the shortest stories in the collection, at under two pages long, ‘My Jockey’ is almost like a prose poem. It is bright and bedazzled with equal beauty and pain. A nurse helps with an injured Mexican jockey who is ‘a miniature Aztec God’ and who, as she undresses him, ‘slept on, an enchanted prince.’ In comparison one of the longest stories at around thirty pages, is ‘Let me see you smile’ and gives voice to a familiar strangeness, a recklessness in the cast of characters. It is a slippery story, hard to follow if attention is not paid as the characters’ names either chime; Jon, Joe, Ben or change; Carlotta/Maggie. The point of view also shifts; from the first person ‘I’ of a lawyer, to the ‘I’ of his client, Carlotta/Maggie. All of this seems to represent the chaos of the lives described, the beauty and bravado of wild feckless drinking, of trespass and taboo breaking that even the attorney finds himself drawn into in the lead up to Carlotta’s trial.

In some ways Berlin’s stories seem full of ease; reminiscent sometimes of stories like Denis Johnson’s ‘Emergency’- tall tales told in a bar that instead of melting into air and fading from memory are written down.

In some ways Berlin’s stories seem full of ease; reminiscent sometimes of stories like Denis Johnson’s ‘Emergency’- tall tales told in a bar that instead of melting into air and fading from memory are written down.

Often they deal with alcoholism – something Berlin fought for many years. The story ‘Unmanageable’ is about the desperate physical condition of a woman in need of a drink – or more drink rather. The first line might be thought overblown, even histrionic and yet it somehow delivers itself up, an eye opener with glimmers of wry humour, ‘In the deep dark night of the soul the liquor stores and bars are closed.’ Perhaps it works because the next line is practical, domestic, banal; an unnamed woman finds that her pint bottle of vodka is empty. She lies on the floor, trembling and to calm herself reads the names of authors on her bookshelf, ‘Edward Abbey, Chinua Achebe, Sherwood Anderson, Jane Austen, Paul Auster.’ This has a marvellous ring of truth to it – the drunk, though unable to stand up has alphabetised her books – and what impressive books, what catholic and contemporary taste she has. But she has to go out, has to go a long way to buy more alcohol, and the story is a description of that journey, ‘Pulling herself along on bushes, tree trunks, like climbing a mountain sideways.’ If that desperate, helpless woman was Berlin herself, then the story ‘Silence’ suggests some of the reasons for her later weakness and self-destructiveness, painting an image of a child who was both neglected and abused, making clear-eyed connections between Uncle John’s actions when he hit a child and a dog with his truck, and her own later ones, ‘Of course by this time I had realised all the reasons why he couldn’t stop the truck, because by this time I was an alcoholic.’

Over and again the cultural references pull me up short and remind me that while the earliest stories were first published in 1961 and 1962 others were written in the 1980s and 1990s perhaps later too, so it should come as no surprise that The Man Who Fell to Earth is referenced along with Metallica, Paul Auster and others that feel close and recent. But Lucia Berlin has been dead twelve years already. In her stories everything and nothing happens, the world is banal, sometimes nightmarish but also touched by a small moments of grace and the kindness of strangers.

Jo Mazelis is the author of short stories, non-fiction and poetry. Her collection of stories, Diving Girls (Parthian, 2002), was short-listed for the Commonwealth ‘Best First Book’ and Wales Book of the Year. Her second book, Circle Games (Parthian, 2005), was long-listed for Wales Book of the Year. Her stories and poetry have been broadcast on BBC Radio 4 and published in various anthologies and magazines, and translated into Danish. Her short fiction has also appeared on TSS and can be read here. Her novel Significance (Seren, 2014) was the 2015 Jerwood Fiction Uncovered Prize-winner. Her most recent publication is the collection of short stories titled Ritual, 1969 which we reviewed here. You can read more about Jo in our interview with her here: The Art of Short Fiction No. 1, Jo Mazelis.