Review by Foye McCarthy

***

There’s an unnerving moment near the end of Denis Johnson’s new collection, at the close of the story Triumph Over the Grave, where the narrator tells us “it’s plain to you that at the time I write this, I’m not dead. But maybe by the time you read it.” The story is presumably autobiographical – like Johnson, the protagonist is an author and a teacher of creative writing. Since writing this story, Johnson has passed away.

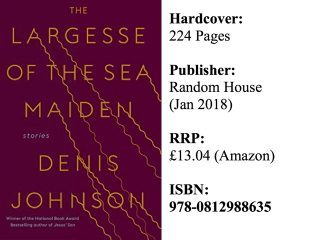

The Largesse of the Sea Maiden is his final, posthumous short story collection, and marks the departure of a master of the form, who was also one of our best novelists and poets – a widely influential writer who earned mass acclaim and some of the highest-prestige awards going. It truly is a loss. So is this collection a fitting note to end such a career on?

Johnson’s characters are far less chaotic now. They’re slow, contemplative and melancholic, rather than ecstatically stoned.

Like the rest of Johnson’s oeuvre, Largesse has profound concerns. Perhaps influenced by the news that he was terminally ill, it casts a wide nostalgic lens over the past, and a deer-in-the-headlights gaze forward into death. The titular story’s protagonist remarks “this morning I was assailed by such sadness at the velocity of life – the distance I’ve travelled from my own youth, the persistence of the old regrets, the new regrets, the ability of failure to freshen itself in novel forms – that I almost crashed the car”. The same character later thinks “Elaine: She’s petite, lithe, quite smart; short gray hair, no makeup. A good companion. At any moment – the very next second – she could be dead.” Like the old Denis Johnson, it’s brilliant prose (so much is achieved with so little). Unlike the old Denis Johnson – with his manic, transcendent Walt-Whitman-as-heroin-addict antiheros in blackest comedies freewheeling through life – everything seems to hum with anxiety. They were the high: here’s the comedown. I think of James Wood quoting his wife Claire Messud in The Nearest Thing to Life on her parents’ death – “There is the strangeness of a life story having no shape – or more accurately, nothing but its present, until it has its ending; and then suddenly the whole trajectory is visible.” If Johnson’s previous characters had an energy and carelessness that seemed utterly present tense, here his narrators are in the severe past tense of something concluded.

But Johnson’s always been metaphysical. His most famous works, Jesus’ Son, Angels and Tree of Smoke have biblical titles, and do something quite startling by juxtaposing these against stories of heroin addiction, murder and war. Like Cormac McCarthy’s Child of God, a novella about a necrophile, or Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah and its prolonged verses on depressing sex, these titles are anything but ironic, but rather want to show that, for the sincere spiritual searcher, one has to balance the love of God/s against the intense misery of this world. One has to see these things clearly if one is to have any claim to truth – nevermind the higher spiritual truths. Geoff Dyer also puts it well in his review of Tree of Smoke: “central to Johnson’s dramatised world-view is the belief that it is the mangled and damaged, the downtrodden, who are best placed to achieve – ‘withstand’ is probably a better verb – enlightenment”

Readers more familiar with Johnson’s early works will be surprised with Largesse – his characters are far less chaotic now. They’re slow, contemplative and melancholic, rather than ecstatically stoned. The titular story has a character attending an award show that seems to be a closer for his career as an ad man, and then a funeral for a friend. He bumps into the lookalike son of an old friend at the award, and asks after his father, only to discover he’s dead. After a chat, he leaves saying “tell your father I said hello”, half-conscious from the shock of how many of his friends are departing, and how close he himself seems to be to the end. Protagonists are more grounded in these late stories: two are university professors, beside this ageing ad man. When we return to the familiar surroundings of imprisoned convicts, we find one has snuck in a magazine with a page laced in psychedelics. He splits it with some jail mates and consumes it and we expect it the verse to fly into the messy poetic transcendence drug use would provoke in Denis’s earlier works but… nothing happens. Our characters’ feet remain firmly planted on the ground, looking forward at the not-much that lies ahead.

But the trails these stories follow are just as fun (and fun is, surprisingly, frequently the apt word) and discursive as any of the ones in Jesus’ Son. We encounter a fondly remembered creative writing student who has dedicated his life to a manic, caterwauling conspiracy theory that Elvis’s twin – who as the official story would tell us, died in the womb – actually survived and replaced a murdered Elvis, which explains the drop in quality in his later work (the plot extends to dug-up graves and disappointment, and the alleged appearance of Elvis’s unusually amorous, freethinking ghost). The ad man receives a phone call from an ex-wife who tells him she’s terminally ill, and halfway through he realises that, awkwardly, he’s not sure which ex-wife is calling. Gallows humour at its highest.

But claiming these things are hilarious certainly makes me feel a bit odd. Perhaps fandom of Denis Johnson is, fittingly, like a religion, and what makes perfect sense to those within seems deranged from those without. You’ll have to make the dive and experience the beauty and wild energy of his prose for yourself, the brilliance with which the man could put a sentence together. I still think about lines from Angels like “all around them men drank alone, staring out of their faces” or Tree of Smoke’s “the dark was thick enough to drink” – a fantastic paradox: as efficient as Hemingway, as lush as Nabokov. I don’t think these five new short stories reach the height of his greatest works, but only because so few books do. They still continuously spark up with beauty, wit and invention, and make up a fitting send-off for a genius.

The fun is also here, on a sentence-to-sentence level, giving redemption to convicts through the beauty it lays over their story.

And all this beauty and fun soon leads us to acquired wisdom, to characters announcing that they have “nothing to show for 36 years on this earth. Except that God is closer to me than my next breath”. Or our Elvis conspirator and his belief in an encounter with Elvis’s ghost defending himself by saying “Life after death, ghosts, Paradise, eternity – of course, we take that as granted. Otherwise where’s the fun?” The fun is also here, on a sentence-to-sentence level, giving redemption to convicts through the beauty it lays over their story, giving pathos to dying professors and wisdom to their thoughts of the beyond, giving humour and an awe of the mystery to the whole.

Johnsons’s method is odd: in the crazed, disorganised-as-drunk stories of Jesus’ Son you weren’t hooked by the usual cause/effect of plots, but by the sheer vibrant energy of the protagonists as they flew through them. Here, what carries you through is the power of these contemplations, the emotional and philosophical depth that emerges from the vibrancy of the prose, the bright light of singular characters as flames about to extinguish. In Walter Benjamin’s essay The Storyteller he cryptically claims “Death is the sanction of everything that the storyteller can tell… he has borrowed his authority from death.” Johnson’s final storytellers have authority and charisma in spades. You could listen to them until they, inevitability, can’t tell any more.

***

Foye McCarthy recently won the London Short Story competition 2016. He was an award-winning student journalist at the Warwick Boar and is also a book reviewer for places such as the London Magazine.