Review by Rupert Dastur

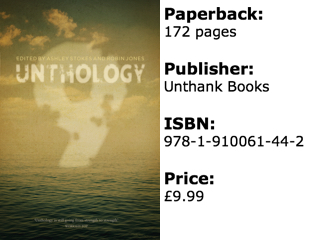

A collection of seventeen short stories, Unthology 9’s most defining characteristic is quality. Stokes and Jones have done a remarkable job of curating a diverse range of talents and tales, weaving them together within the atmospheric seascape cover designed by Robot Mascot.

The opening short story in the collection, ‘I’, begins with a favoured topic of short fiction writers (mortality): ‘Apparently drowning is the most euphoric way to die.’ – an arresting first line from Rosie Gailor. The piece is structurally, but intentionally experimental – past and present sequences, punctuation, and fonts (dashes, ellipses, capitalised sentences, italics) are effectively employed to exacerbate the dislocation and detachment of the narrator, while the conversational tone, signposted by that initial use of ‘apparently’ continues throughout. The net result is that a relatively well-swum narrative is made fresh and compelling. We are lulled into the drowsy memory-state, slip into the self-involvement of the speaker, sink into the warm water, head submerged, waiting for the silence…

Play with style and form continues in SJ Butler’s short story ‘May Day’ – one of the more complicated works, necessitating a few readings in order to feel the full effect of the rhythms, repetitions, and progressions. The wave-like, rolling tale, often eluding the full stop, gives the impression of an inevitability which the central protagonist, a simple man called Harry, is without the means or wherewithal to escape. The child-like character moves through memory and space tragically caught within the currents of his situation.

Juno Baker’s contribution, ‘A Trip Out’ likewise deals with a man who struggles to deal with the outside world and is equally alone and without help. The difference here is that in this short story, Jim’s predicament is, arguably, self-inflicted. Our man in town grows marijuana and following the best green-fingered advice, he even talks to his plants. When an accomplice, the ironically-named Spider, fails to show up with sacks of Feed ‘n’ Grow for Jim’s crop, the addled oddball has to venture out. As expected, the results aren’t positive. It’s a strong piece which snapshots the sad, low-key, small-time characters in the drug world, whose situation seems so pathetic in comparison with the glitzy bling of TV drug barons – it almost elicits sympathy.

It’s not all doom and despair. As the collection progresses, a sense of survival, birth, renewal, and rescue surfaces. The last short story in the anthology, ‘Yellow’ by Roelof Bakker is a touching work exploring loss. Ashley and Stokes nicely bring the book full circle with this text which begins with a loose refraction of Gailor’s start: ‘They say it’s the strongest swimmers who drown.’ More traditional in style, the story follows the narrator as he comes to terms with the death of his partner, Marek. Loss is a popular subject, but Bakker offers precise prose that avoids cliché, giving us original lines that bubble up beautifully through the paragraphs and are full of emotive veracity: ‘I’m only happy when I swim. Bits of Marek live on in the water, traces of his DNA remain wherever he’s done the butterfly, the breast-stroke. When I dive in, I delve into the past, back into his arms. Memories bob to the surface.’

‘Breathless’ by Jane Roberts is one of the shorter stories – placed third in the collection it’s more solid, more bodily than the former two by Gailor and Butler – both in terms of style and content. Like Bakker’s story, the piece is concerned with love between two people. ‘Sometimes I find it hard to breathe. Oxygen. It’s like love. It’s all around.’ So goes the beginning. Occasionally the lines can veer into the slightly sickly (‘That’s him. Tom. That’s love. That’s oxygen.’) – although the reader shouldn’t be fooled because this isn’t Love Actually, being closer in tone and matter to The Fault in Our Stars.

Love remains a complicated thing in many of these short stories. Judy Brikbeck pens a short story about a husband (composer) and wife (painter) who move to the countryside for ‘a fresh start’ – a first sentence so easily glossed over, but so significant. The husband dashes around being splendid, while leaving his wife at home to paint. She takes long walks and encounters the violence of the rural world. Parallels, a few choice metaphors, and various clues drip through the prose – some of it noted and some of it missed by the husband whose self-involvement is accentuated by his first person narration. Although I partially question the suddenness of the ending, I remain a strong fan of this short story which becomes increasingly complicated the more it’s pondered.

‘My mother twitches with sex’ – so commences a hard-edged short story (‘As Linda Was Buying Tulips’) by Sarah Dobbs. Here we have an artist son who is uncomfortably obsessed by his twitching mother and her breasts. Throw in a successful father and we’d be screaming Oedipus Complex like every modern-day English lit. student. But there’s no father here. Instead, we’re given the infinitely interesting Linda, and as the narrator notes, ‘neither of us expected Linda.’ She’s fast and fun and frolics and fucks (the language isn’t shy either) with fair abandon. Although the plot twist seems one turn too far, this is a small quibble for a cracking read that injects a strong shot of punchy prose into the book as a whole and remains one of my favourite in the anthology.

We’ve come across John D. Rutter before at TSS (read his story here) and it was a pleasure to see him appear with the piece ‘My Knee’. The title is mundane, but brilliantly so, providing much in terms of tone and style; the reader is given an immediate impression of the narrator: middle class, married, a little dull, and suffering marital problems. The couple have lunch at ‘The French’. The husband drinks wine and his suspicions and aggravations surface. Everything comes to a climax, a crash – metaphorically speaking, and literally. There are some lines which really capture the bitterness of relationships gone wrong, highlighting Rutter’s ability to pinpoint emotional truths succinctly: ‘”It’s not just a fling.” That’s what Pippa said last night, as if somehow a fling would be alright.’

Svitlana and Yuri, a Ukrainian couple with a baby, fare little better in Nick Sweeney’s short story ‘Traffic’. Written in a deviously chirpy manner and with a plot twist that brings a wry (and appalled) smile, it’s easy to overlook the darkness within which this domestic scene is cradled: ‘Ukraine was imploding in the face of threats by outsiders, and by its own nationalists, gaping with shortages, hospitals no good, services gone to ruin, political life reduced to slogans shouted by stupid men with guns.’ It’s a world in which the word ‘traffic’ refers to people, not cars. It’s an excellent read and Sweeny conjures the two personalities of mother and father, expertly pitching them against one another.

From Ukraine to Russia. Tim Syke’s ‘Marlboro Country’ gives another bleak environment with ‘broken windows, rust and flaking paint’ but it’s set in the wider city of St Petersburg with its creeping modernisation and Americanisation – the western world rubbing up, sometimes uncomfortably, against the traditions and older styles of the place. Told in the first person, we accompany a young man from cancer bed to cancer bed in a deathly institution, and from street to street in what seems a different, difficult world. Perhaps it’s the walking, the interiority, or the flights of fancy, but there’s something almost Joycean in this piece. I liked it.

Interestingly, the last nine or so short stories, and twelve of the total eighteen, are written in the first person. ‘Scapegoat’, however, takes the greatest liberty with point of view, switching between first and third person in a complicated narrative that circles over a deeply disturbed, lonely, (sociopathic?) banker who is paid to make ‘big money’. As a reader, I’m wary of the cliché in Bret Easton Ellis-type characters (American Psycho, 1991). Nonetheless, Tim Love does a solid job in casting his troubled protagonist in varying colours, helped by the contrasting perspectives, using the trope as a trampoline to reach more engaging heights as Charles obsesses over his firm’s ‘newest recruit’ Lucy with her ‘beautiful arms’ and ‘delicate fingers’.

The penultimate short story from Tania Hershman (interviewed by us here) demonstrates the diversity Stokes and Jones bring to their anthologies. ‘About Time’ is driven forward by the fast-paced, chatty, no-nonsense voice of a writer researching, of all things, time machines. Self-referential, dare I say meta, the direct, conversational story is established from the offset. ‘I’m trying to write a short story about time machines. I know what you’re going to say, you with your nice face, your neat hair. Yes, nice. I know that’s not a word writers are supposed to use, but I’m reclaiming it.’ Reading this story, I felt as if I was sitting in a café, or perhaps a bar, listening to an animated friend tell of her latest adventure. She’s a talkative character, for sure, but she’s interesting and amusing, so the listening is a pleasure. Our writer meets someone who’s had the fortune to travel in a time machine. They talk. We listen. Then something strange happens. It involves a plant… This event puzzles us and our narrator. We’re still scratching our heads when the last paragraph is dropped with great aplomb – a short prose bomb that scatters all the words so that we’re forced to reassess the landscape that’s been set out before us. It’s fitting that a story about time tempts us back to the beginning.

Where Hershman’s story involves a great deal of movement, the lengthy short story ‘Motes’ is more concerned with sitting still. Still enough to collect dust. Similar to Hershman’s story, however, Mark Mayes creates a lucid, likeable character who propels the plot onwards. The writing is clear and concise, and begins by catching the ennui facing so many of those searching employment. Eventually our hero does find a somewhat unexpected vocation, but despite its peculiarity it affords him enormous satisfaction and a sense of purpose. Like some of the best short stories, it lightly offers social commentary, cleverly manoeuvres between the funny, the weird, the sad, and ends with a disturbing, gut-wrenching bang. It’s one of the stronger short stories I’ve read this year. Bravo, Mark Mayes.

A handful of these short stories are inhabited by strange people and stranger happenings. Editor of the successful anthology Being Dad, Dan Coxon’s contribution seems simple on the surface and the plot can be loosely given in a few sentences – but the more you comb the lines, the knottier it becomes. The story revolves around a delivery-driver called Greg, his sister, and a collector of Germanic porcelain figurines. One of these figurines has the uncanny tendency to disappear and reappear. There’s an interesting tension to be had in the symbolism of a delivery-driver – a man who should know where he’s going, who drives and delivers, and that’s about it. But there’s always the element of the unexpected to steer the narrative off course, so that nether Greg nor the reader quite know what road we’re following.

Stranger still, is a kidney which is surgically removed from the narrator (Richard) and then anthropomorphised by his wife and his sister-in-law, to the extent that this bean-shaped organ watches television, wears a watch, goes on dates, and spends significant periods in the bedroom. In the meantime, the husband walks and talks in an understandably constant state of confusion. The kidney fills Richard’s shoes, so to speak, while the husband himself is regarded as ‘body parts’ that should have been disposed of. It’s tempting to delve into questions of identity and relationships, but that would probably spoil the fun in this short, but wonderfully readable piece by Gordon Collins.

After reading this anthology, there is a sense that the editors enjoy fiction that contains a degree of precision, of authorial knowledge brought to bear on the work – there is a certain level of technicality and research evident in many of the pieces. It’s evident in two short stories that follow one another – ‘In Rehearsal’ by Sarah Evans, and ‘Double Concerto for Two Violins’ by Jonathan Taylor. The latter story is one of music, memory, and war. Jonathan Taylor’s work is saturated with italicisations: vibrato, sicilienne, forte, ritenuto but also kapo, Selektionen, and Lagerführerinnen. These tensions of war and music blend so that the form and rhythm of this piece impressively fits the content, while the rising pitch corresponds with the narrator’s epiphany at the close of the song, as a voice calls out from the old woman’s past – ‘Frieden!’.

Jostling among my favourite pieces in this anthology, Sara Evans has written a deeply touching short story focusing on a new-born baby who needs a complicated operation to fix the circuitry to the heart. Evans masterfully captures the surgeon’s voice, creating a narrative that is utterly compelling. We are privy to the pressures that must daily circle the minds of those working in such extreme circumstances of life, death, and cutting-edge surgery – worry, anxiety, excitement, possibility, reputation, statistics… a whirlpool of mixed emotions and decisions that had me biting my lip in agitation, right until the last sentence.

The final word should be given to the editors who have worked hard to bring these anthologies to fruition. The pieces are meticulously edited and despite the diversity in styles and subject-matter, there remains a cohesion, a flow from darkness to light which makes the book a thoroughly satisfying read as a whole. These writers and their stories deserve a voice and the excellence of Unthology 9 demonstrates the importance of independent publishers like Unthank who provide a platform for some of the most exciting contemporary literature. Here’s to the next one.

Unthology 9 can be purchased directly from the publishers here.

Rupert Dastur is a writer, editor, and founding director of TSS Publishing. He studied English at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he specialised in Modernism and the Short Story. He has supported several short story projects and anthologies and his own work as appeared in a number of places online and in print.

Support our reviewers by donating here.